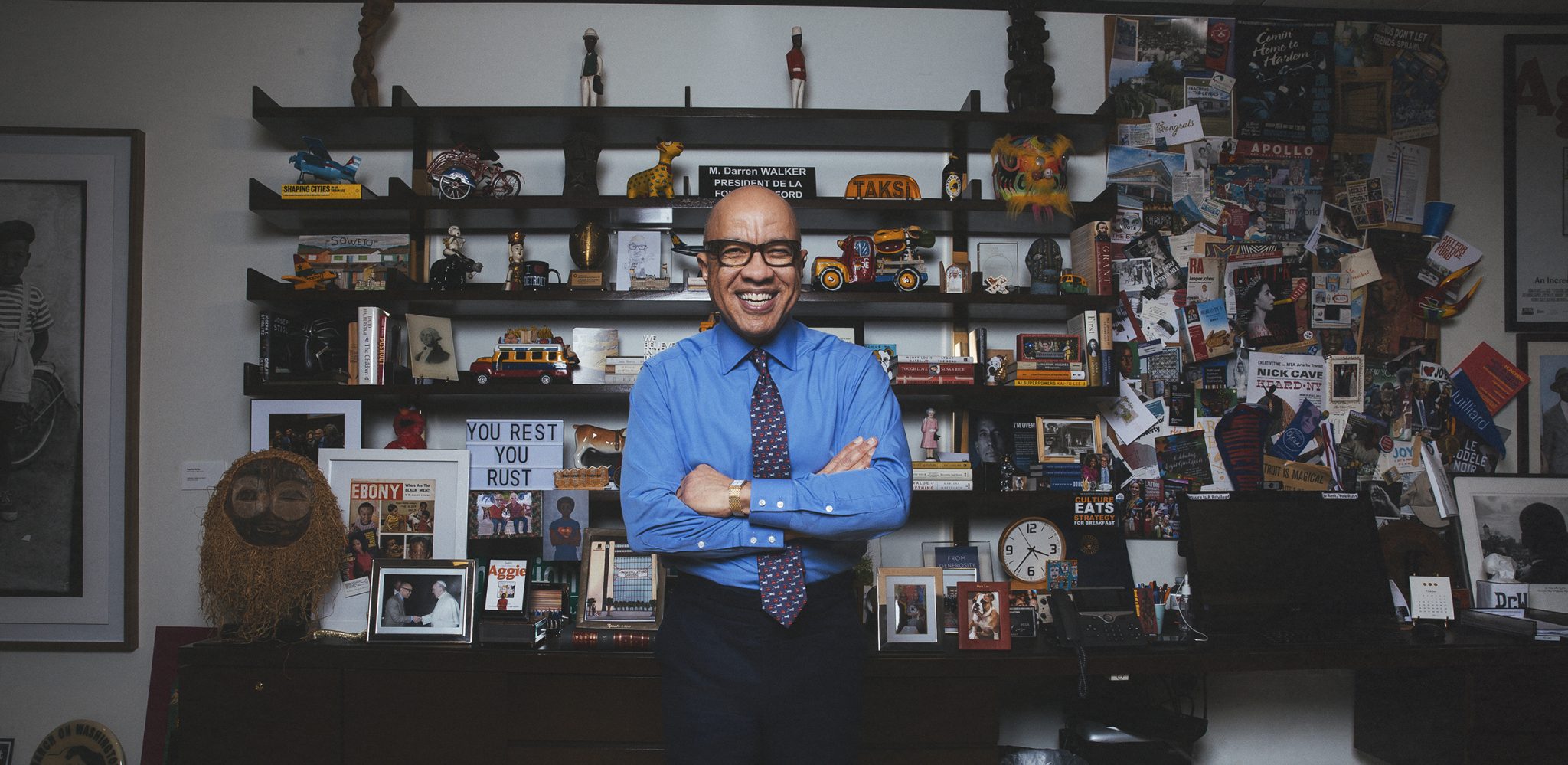

With a background in finance and philanthropy, Darren Walker serves as president of the Ford Foundation, a private US organisation created in 1936 by Edsel and Henry Ford, but now completely separate from the Ford Motor Company, with a mission to advance human welfare. The foundation is the second largest in the US, with an endowment of $13 billion. The Ford Foundation supports a number of arts organisations and states that it is ‘imagining philanthropy to catalyze leaders and organizations driving social justice and building movements across the globe’.

Tom Eccles You came on as the president of the Ford Foundation seven years ago, and since then you have really shifted its mission towards a focus on issues of social justice and equality. How has that shift and focus impacted your thinking about the arts and what you support in the arts?

Darren Walker I think our focus has shifted to addressing inequality in all of its forms. Social justice is a philosophy that we bring to philanthropy and philanthropic practice. It’s why I talk about social-justice philanthropy, which is a particular kind of philanthropy. The focus on inequality has resulted in having an analysis of the ecosystem of art and culture in this country and the way that ecosystem manifests forms of inequality.

It does this in the way it does in most other systems in our country, through the lens of race and gender, class, geography. People are often marginalised, discriminated against and have, for generations, been left out of the narrative of art and culture. At the end of the day, one important function of the arts is to tell us who we are as a people, and to playback for us the narrative of America. We know that the arts have not fully engaged in that narrative, that the arts have, in many ways, served to perpetuate partial storytelling of American history and culture.

What we are interested in for today is ensuring that the full, rich, vibrant, diverse story of a culture in America is told. In terms of a grant-making strategy that leads us to disproportionately fund organisations that reflect people of colour, indigenous people, people who have historically been marginalised. You can look at our most recent initiative, America’s Cultural Treasures [a national and regional initiative to acknowledge the diversity of artistic expression and excellence in America and provide critical funding to organisations that have made a significant impact on America’s cultural landscape, despite historically limited resources], as a manifestation of that view, our largest arts initiative in over a decade.

At the end of the day, we expect that probably $200 million will be raised [as of September, monies raised already totalled $156m]. The board is contributing $81m of that, but the remainder is coming from other foundations around the country. There will be probably 50 to 100 grantees, ultimately.

TE You spoke at one point about the Ford Foundation being interested in looking at the metrics of its results. What are the metrics you use in terms of thinking about organisations that you will support?

DW I want to be really clear, some of the most important things in the world that ensure fairness, diversity, justice, equity, cannot be put on a spreadsheet. I am actually not a proponent of trying to create mathematical equations to understand the value of art. I do, however, believe that we need to understand the impact we’re seeking.

One of the changes at the Ford Foundation since I’ve been president is that most of our grant-making is general operating support. We don’t do significant amounts of project support that we can isolate in our grant and track that specific project, that specific exhibition or that specific intervention. We support what I call the three I’s: ideas, individuals and institutions. When you support institutions, with general operating support, you’re supporting the strengthening of the institution. The metrics for that are metrics that measure the quality of leadership, the strength of their board, the financial resilience, and whether those things improve over the life of your grant, and can the improvement be reasonably attributed to your grant? There are ways of measuring that.

But I think it was Oscar Wilde who reminded us that many of the most important things in the world cannot be measured. And the things that we measure are often not important.

TE Around three years ago, the New York City Mayor’s Office initiated Create NYC under Tom Finkelpearl. It’s an initiative that really questions boards of the city’s museums. Who are their audiences? What is the diversity on the boards and in the staff? They made it clear that they were not going to talk about funding in relationship to that, but it was a red flag that was set out there, indicating that this was going to be looked at over the next few years. Do you think that’s been effective or will be effective?

DW Absolutely. First, I commend Tom Finkelpearl for that initiative. I think part of the initiative was to, what I call, surface, name and frame the issue. Because the city had never actually established a dialogue about this with the grantees who received city funds. It put clear strategy requirements in place for every organisation to have a conversation with the board to demonstrate a plan of engagement. To actually conduct a census of their staff to understand the demographics, some census of their audience. These were important interventions for the city to encourage.

I think the initiative has been successful to the extent that it has helped change the conversation. I think some organisations were already on the journey and this just helped; I think others have gotten on the journey. As you know, so much has changed in the last few months, I think that there are many other vectors of pressure that boards and leadership of museums are feeling and that it’s not really the city that is putting the heat under these institutions anymore. Those other vectors include, most prominently, the staff, artists, stakeholders who are patrons and supporters and who have an interest in the museum. These are the people who are really publicly and on social media challenging museums to do better.

TE Does the velocity of the current ‘reckoning’ surprise you?

DW I think the velocity has not surprised me. Because the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement sought and successfully achieved an impact in, literally, every dimension of American life. There is no industry, no sector, no domain of American life where a conversation about race isn’t happening. I don’t expect that museums would be immune from that. The velocity is, in part, the intensity and the energy that emerged from the marches in the streets, from the discussions in corporate boardrooms and within museum boards and many other places where influential people gather. For the first time in this country there was a reckoning with the reality of racism. Because before the murder of George Floyd and the Movement for Black Lives this summer, racism in America remained deniable by white Americans. Deniability was an option.

The Floyd murder, I believe, took deniability off the table. It is no longer possible to say that there is not some systemic racism in our country rooted in our history of white supremacy and our history of a racialised caste system that we have ignored and, in many ways, sought to erase. This is the work of culture. This is the work of the arts to address the historical erasure of narratives that are unpleasant and challenge the idea of American exceptionalism, and now align with our romanticised view of who we are as a people.

TE I remember hearing Fred Moten and a number of other great speakers at a talk just days after the election of Donald Trump. What struck me was that the speakers felt that there’d been violence done to their own body, through attacks rooted in language. It made me feel that I needed to rethink this in terms of the difference between violence and harm. Do you think that in this moment the definitions, liberal definitions of what offence is, what harm is or what violence is have changed?

DW I believe that there’s a recognition of the harm: things that may not have been perceived as harmful by whites in the past are acknowledged now as harmful. Look at the Guston controversy. I am a believer that there is never a wrong time for art. There is never a bad time to show a painting to engage the public. But, for the first time in my life, I agreed with Kaywin Feldman’s [director of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC] recommendation to the trustees of the gallery when she raised the issue of the harm and pain of the imagery, irrespective of Guston’s antiracist and courageous engagement with that toxic imagery.

Historically, Guston’s words were enough, considered enough by the art intelligentsia to allow what is clearly painful, harmful, toxic imagery to many people, certainly, to many people of colour. That is not to say that Black people cannot absorb and observe imagery that makes us uncomfortable. African Americans and people of colour have lived with imagery that makes us uncomfortable for our entire history in this hemisphere, so it is not that we are snowflakes and unable, it is that context matters.

The context of October 2020, is that we are living in a time when at the highest levels of our society, white supremacy is being legitimised and valorised, imagery of lynchings, of clansmen is being appropriated by people who seek to do harm. Black people and others are truly feeling a level of pain that many have never felt. Because it is the compounding vectors of the pandemic that have disproportionately affected African Americans: the economic fallout and those who are most likely to suffer from this – the low-paid essential workers, who are then most vulnerable from having to work in the middle of a pandemic – while the rest of us can sit comfortably in our homes and work virtually; and the political climate, which feels hostile.

It is the confluence of all of this that, in my mind, led Kaywin to make that recommendation to the trustees. We, of course, supported it because I think she was bringing us a message, not only from the staff of the National Gallery but from others, particularly, other people of colour who had never been engaged.

This was actually less a decision about Guston and more an indictment of the lack of preparedness of museums like the National Gallery to exist successfully in a new future. It was about how old playbooks and old ideas need to be updated and cannot be slavishly adhered to. As I said, most of the criticisms were from people who felt like me, “What do you mean? Right now, we need Guston more than ever. We need art more than ever. There is never a bad time for art.” That’s what I would have said a year ago, but the context matters.

While some critics would say that what Kaywin did was cowardly, I would say it was courageous. Because, ultimately, we will be able to map out an exhibition that is seen in the proper context, hopefully, in an environment where racism and the kind of white supremacy that we’re seeing in this moment will have subsided.

TE It contradicts my thought. Because I was reading about all of this and thinking, “OK, who would actually have the authority to stand up and say no to the show?” Given a consensus around Guston, I thought, “Well, the only person who has the authority to say this is definitely Walker.”

DW I don’t have the authority. I’m one person who brings up an opinion. I’m not naive. I understand that I speak from the platform of the Ford Foundation. Therefore, I want to be thoughtful and reflective as I was when I said what I said publicly – a simple statement: that context matters.

The context in this country around race has fundamentally required us to excavate this convergence of race and art and representation. Who narrates? Who is the audience? When people say things like, “The audience will understand this” – you’re insulting the audience. Who is the audience? We know who historically has been the audience and if that’s the audience you’re talking about, you’re right – if you’re talking about the audience of white elites, who have traditionally been the gallery’s visitors. Because the reality, sadly, of the gallery’s history is that it has not been a place that has welcomed the people of colour.

In the National Gallery’s history, it has staged only three exhibitions by African Americans. Among its staff, most people of colour are the guards, the art handlers, the movers, the porters, the people in administrative support positions. There is not a history of African Americans being in senior professional roles. There is no African American curatorial staff member and yet you are going to put paintings up of black men being lynched that are 96 inches square, in the largest gallery of the museum and you haven’t talked to any Black people in the building about what they’re going to see when they come to work every day. I’m not saying don’t do it. I’m saying, we need a process that is more consultative and we need curatorial sensibility that understands that it is not just the curator’s idea that matters.

That is a new phenomenon. Because most curators were not trained to believe that the views of other people really matter that much. Now, I’m generalising a bit, but curators have been rewarded for being the singular force behind the idea and the relationship to the artist. Not for bringing a group of African American staff into the auditorium and having a conversation with them about what they think about this painting, and how to best present the painting, and how to best engage people like them.

TE So what’s in question is the very structure of the museum?

DW Yes. This is my point. This is why I love Guston and I regret that people have conflated the more important question here, which is ‘What is the future of our museums?’ My view is that the future is not bright if museums continue to be the museums of the past. In a more diverse and increasingly sophisticated international multicultural America, museums are challenged. Because the role of museums in society has been to narrate the American story, to narrate American identity and to hold a mirror up and say, “This is who we are.” That’s been the work of museums and not just in America, but in civilisation as a whole.

Until recently, there was a pretty well-established idea of who we were. It was a Western-European hierarchical, patriarchal etc, society. That idea wasn’t being debated ten years ago. Back then it was demanding to know about the lost African-American modernists who we now know about. No one ten years ago was asking these questions about Alma Thomas and all sorts of artists who have been ‘discovered’ in recent years. Because now the idea of who we are is in the process of changing.

That generates a level of contestation and discord and dissonance that makes a lot of museum professionals uncomfortable. Because it highlights their culpability in sustaining a system that reinforced the racism, the exclusion, the patriarchy of the past.

TE Two recent cases stand out (but there are more). The chief curator of the Guggenheim [Nancy Spector] has resigned as did the senior curator of the SFMOMA [Gary Garrels], both under different circumstances. You’re starting to see a domino effect hitting the people at the very top. When I came to New York, they were gods. Is it in the very nature of this change to call for a radical rethinking of the leadership of our museums?

DW Yes. It does call for that and it calls for we progressives to not be so arrogant as to think we don’t need to change, and that we don’t contribute to the problem by our own arrogance and our own insularity. We progressives are also culpable in creating this system that has excluded far too many people and far too many artists and far too many stories.

TE If you’re a middle-aged curator, relatively high up in the hierarchy of a museum, you’re going to start to feel very defensive right now… A lot of people are going to feel very defensive right now…

DW Yes. I want to be clear and fair. I think there are a good number of white curators who worry that they may not be being seen and treated fairly by their critics, and who may, rather than engaging, withdraw from the journey that we all have to be on. That would be a shame, because we need those curators to be on the journey. We need not engage in a cancel culture or an unwillingness. We progressives shouldn’t be intolerant.

Those people like me who want museums to change don’t want to become intolerant of others who don’t see our view. I do want the people who want to be in allyship to see that there is a lot of room to work together. This is not about trying to call out people, at least not from where I sit. I think it’s a mistake to vilify individuals unless they truly deserve to be vilified. I think there is too much gratuitous mean-spiritedness in these discussions. I think we do need to tamp down the incendiary rhetoric.

TE I was thinking about Garrels, who I should say was not a personal friend. The New York Times called me and they said, “Garrels has made this mistake in a meeting where he was presenting an impressive turnaround for SFMOMA in terms of actually committing to buying work and acquiring work and showing work in a very different form than they’ve done historically. He made a comment at the end. Then this accelerated into the notion that he was a white supremacist.” I said to them “Gary Garrels is not a white supremacist.”

DW No, he is not a white supremacist. The unfortunate thing is that good people have gotten caught in bad systems. What I mean by that is, we have in this country an ecosystem, a museum ecosystem that has flaws and racism embedded. That is the context through which a remark like that is interpreted, and it can be interpreted in a way that attributes racism to the speaker. I don’t think that Gary is a racist, that’s absurd – I know him. He has operated in a museum system that is racist. We need to understand why the system makes us all vulnerable. Therefore, have to name that issue of the systemic and that we are all a part of that, and we all have a role to play.

I think what happens is, museum leaders are often unwilling to engage in that higher order recognition, and focus on initiatives like, “We’re going to buy more African American art,” which we do need. That’s right. But there has to be something bigger and more important than simply saying, “We’re buying more African American art.” Museums have bought African American art before. We’re familiar with the idea of putting the work of Black people and objectifying and fetishising the creativity of African Americans and Africans since Picasso. I mean, this is not a new phenomenon, so you’re not going to necessarily win a lot of friends by just saying, “We’re going to sell this important painting and buy some Black art.” That is not, alone, a reason for exhortation.

TE When you came to the Ford Foundation, you sold a number of works and then replaced them. Right?

DW You mean the Ford Art collection? Yes. We sold the entire collection. The history there is that we had the Ford Foundation Art Collection from what Henry and the leadership acquired in the early 1960s. There were over 400 works, all Europeans and some Americas but mostly European, all but one artist, Sheila Hicks, male, and I recommended to the trustees that this collection was not aligned with our value and our mission for the twenty-first century. They agreed. We deaccessioned, we’ve sold that at Christie’s, and took the proceeds and acquired by now about 300 works, mostly by people of colour, women, indigenous, queer, very international. The first piece that we bought was the large Kehinde Wiley portrait of Wanda Crichlow that is in the lobby of our building.

TE I thought it was interesting that you also pushed back on a current trend, given the COVID-19 situation and financial difficulties, that museums have been given a green light to sell artworks in order to fund operating costs. You were quite a lone voice in saying, “I think there are other ways of doing this, without deaccessioning to pay for operating costs.” Am I right?

DW I said that for some, deaccessioning was an appropriate strategy. For others, they have the wherewithal without the necessity of deaccessioning. What I believe is that there is no cookie-cutter formulaic way to approach this question of how to address the operating budget deficits in a crisis like a pandemic.

There are some museums that have very little endowment, that have very little operating cash flow, and for them, where they have debts, I have no problem with what Christopher Bedford is doing at the Baltimore Museum of Art [the plan, involving the sale of works by Brice Marden, Clyfford Still and Andy Warhol to raise funds, is currently on hold]. I don’t think MoMA needs to do that. Because MoMA has got a board that without selling one piece of art can absolutely underwrite their budget deficits.

TE Are you optimistic that museums in the United States will meet the challenges of social justice and equity within the next ten years?

DW Let me just be very clear. I am very bullish on museums in this country. Because there has been an awakening, unlike anything I have ever seen, among museum leadership and museum boards. While the response has been sometimes clumsy, and there have been missteps, I believe that most museums in this country are led by people who want their museum to serve all the people in their community, and who are committed to true diversity, to telling the full story of American art and culture and creativity. Yes, I am very, very optimistic about America’s museums.

Tom Eccles is executive director of the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York

ArtReview’s Power 100 – the annual ranking of the most influential people in art – is out now