The disabled experience is increasingly visible in the artworld, yet an ableist political landscape is constantly on the attack. This affects us all

At Goldsmiths CCA in London a few Sundays ago, the Feminist Duration Reading Group held a collective reading of extracts from my book, Ill Feelings, a firsthand chronicle of illness contested by the medical profession and a history of mother–daughter relationships through the lens of art and literature, four years after it was published. Back in 2021 there was a feeling of hope swelling within the anglophone disabled community that the pandemic, a mass-disabling event that disproportionately affected disabled people, might also bring about positive change. People would have to listen to crips, we thought, and turn to them for their knowledge of mutual support and care. Yet in 2025 we found ourselves reeling from the Labour government’s announcement of the biggest cuts to disability benefits on record. Politicians are calling the cuts a ‘shake up’, to make them sound lively rather than what they are, which is life-threatening. These welfare reforms, intended to save the state £5 billion, will penalise disabled people and increase the number in poverty. Almost half of working-age claimants will lose their award, including over three quarters of those with arthritis and other regional musculoskeletal diseases, half of those with multiple sclerosis and a third with cancer.

I wrote Ill Feelings to counter the myth that disability is biological and individual, arguing that ableism, a form of societal oppression, is what shapes the disabled experience, not the sick body. I wanted to resist the kind of sentiment that every disabled person, regardless of their condition, diagnosis or impairment, has heard from people in their life: that if they tried harder, if they really worked for it, they could choose to be better – more well, more productive – than they are. When I was young, my mother (with whom I share an illness, myalgic encephalomyelitis, or chronic fatigue syndrome) was told we had a ‘shared hysterical language’, that we were conspiring to make ourselves, and each other, sick. Thirty years later, Keir Starmer invokes the ableist stereotypes of disability to defend profoundly dangerous cuts to welfare, claiming that disability benefit fraud is rampant and decrying ‘worklessness’ as a ‘lifestyle choice’.

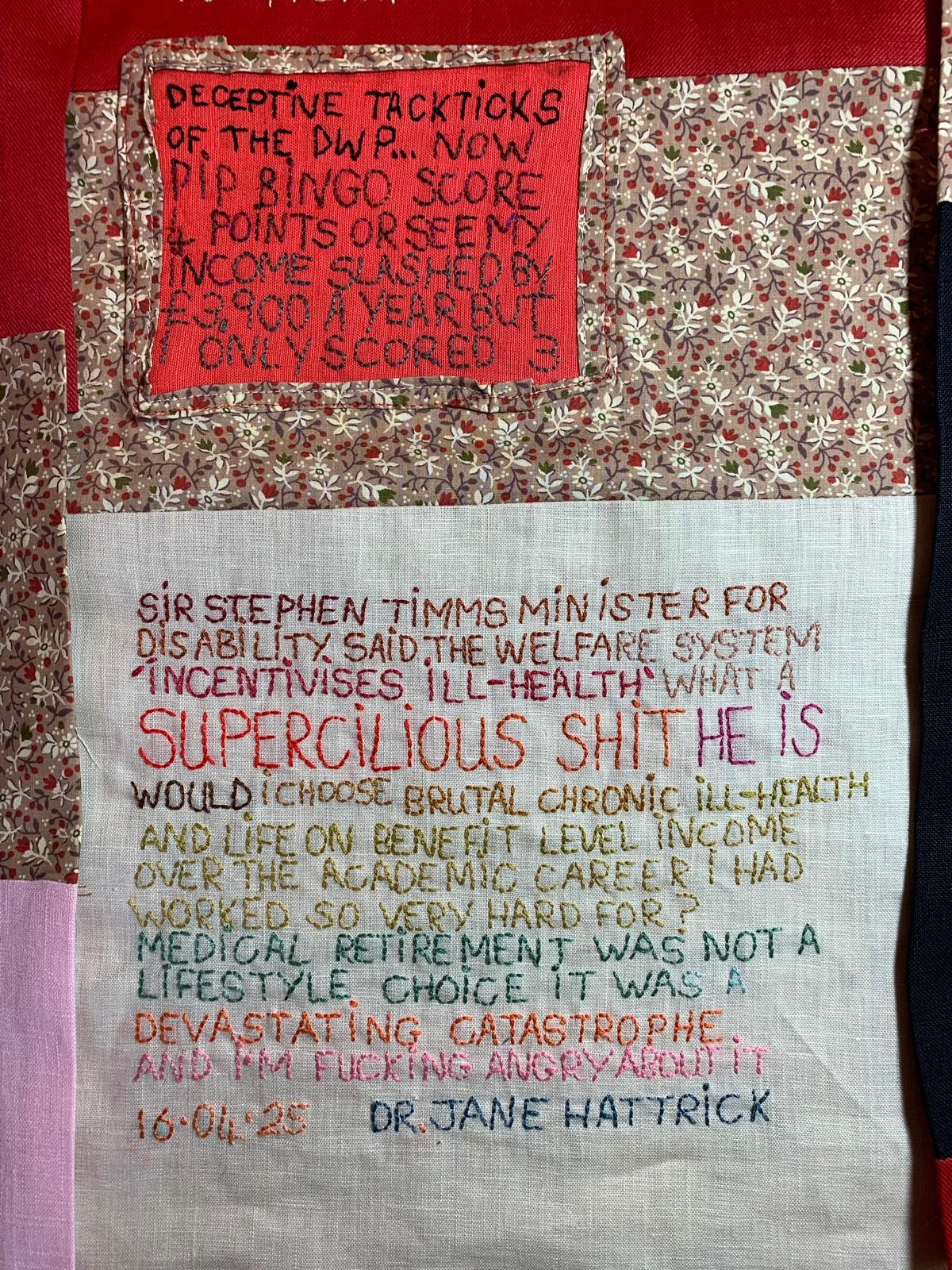

The UK’s disability benefit system is already punitive and demoralising, designed to deter you at every stage. The government’s so-called improvements will exacerbate an already traumatising process. Personal Independence Payments are awarded using a points system, for which an assessor will establish what you can and can’t do across several ‘daily living’ categories, from preparing meals and washing yourself to understanding verbal communication. This already does not serve people with fluctuating conditions, who might be able to wash themselves or cook a simple meal one day and not the next. The government’s ‘shake up’ requires that only those who score a minimum of four points in at least one activity will be eligible for the daily living component of PIP, in addition to the existing eligibility criteria. My mother doesn’t have any fours because she told the assessor she could sew, despite a huge decrease in her mobility since contracting COVID-19. She will lose £75 a week. The assessor took a point off for mobility because being able to sew suggests ‘adequate upper limb movement dexterity and grip’. Stitching is her form of LGBTQ+ activism and connects her to other people in the community. When my mother told the assessor she could sew, what she meant was: sewing is all she could do.

I told the Feminist Duration Reading Group that my mother was “rage stitching” – slowly, with lots of breaks, so her hands aren’t in too much pain – as part of East Anglian artist Dolly Sen’s ‘Lorina Bulwer Legacy Project’. Bulwer was interned in the ‘Female Lunatic Ward’ at Great Yarmouth Workhouse during the 1890s, where she stitched a livid autobiography, littered with the names of the people who had wronged her. Words and letters are picked out in different colours, depending on the background fabric, and some are underlined for emphasis and clarity – they were meant to be understood. Bulwer’s stitching might have only been encouraged as a form of distraction, a keeping quiet, but her embroidered scrolls materialise a commitment to her own existence.

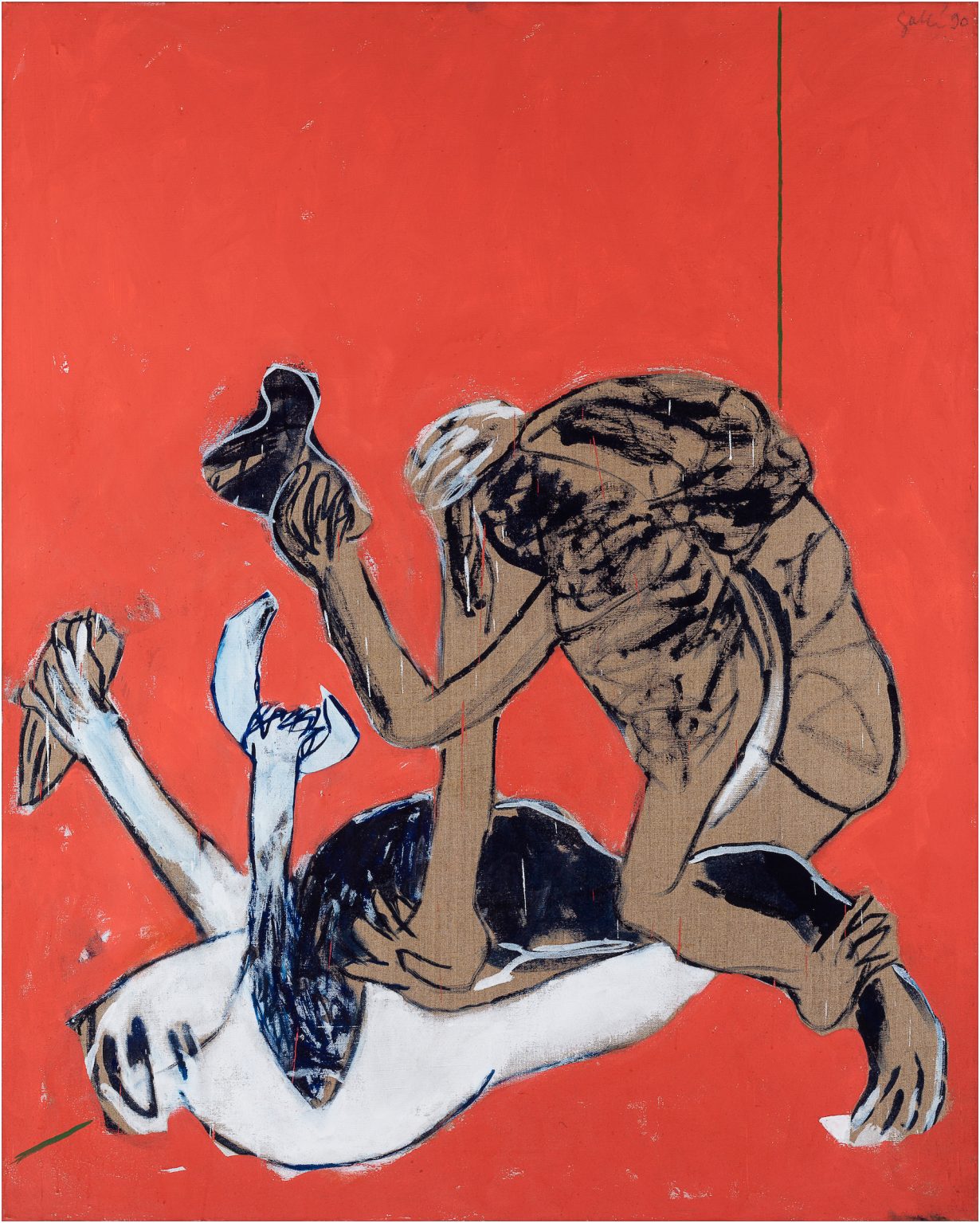

In the neighbouring galleries at Goldsmiths CCA that day were works by the German artist Galli, in the exhibition So, So, So: drawings, largescale neo-expressionist paintings and index card works, mostly produced during the 1980s and 90s in West Berlin within growing countercultural movements advocating for queer and disability rights. Her genderless figures are wounded, deformed. They inhabit bare rooms, everything comfortable emptied out. The works are remarkably physical, visualising the vast effort used to produce them, and through this physicality violent and sensual imagery emerges. The figure in Kentaur (für Schari!) (1990) is all hooves and arms, one of which holds a paintbrush. Another arm reaches back to extract a knife – or plunge it deeper into their flesh. Body and knife and walls hum with red. In her drawings, creatures are obliterated by pencil marks. As a person of small stature who lives with severe health and mobility restrictions, Galli doesn’t represent the disabled experience as distinct. Her works explore something universal: the body as a site of struggle and oppression. Human, animal and myth merge and transform, fighting against these categories and binaries. As the artist has said, ‘The body as a battlefield – that applies to everyone.’

At the same time, London’s Whitechapel Gallery has staged Visceral Canker, a survey of Donald Rodney’s work, also from the late 1980s and into the 90s, before his death due to complications with sickle cell anaemia in 1998. An influential figure in the BLK Art Group in the UK, Rodney worked across an array of mediums, often incorporating the imaging techniques of modern medicine. Rodney’s works show how the medical gaze is inextricable with racial violence. In largescale photographs, his body is shown up close, highlighting long ridges of over-stitched surgery scars; because of his race, the gallery text tells us, he was regarded by surgeons as able to withstand more pain – more trauma. As evidenced by images of his hair taken through an electron microscope (Flesh of My Flesh, 1996) alongside those of fellow artist Rose Finn-Kelcey, there is nothing different about his body at a molecular level. Elsewhere, My Mother. My Father. My Sister. My Brother (1996–97), a miniature house made of slices of his own skin, left over from surgery and pinned together, is too fragile to be shown in exhibition form. Instead, we see it cradled in Rodney’s hand in a largescale photographic print (In the House of My Father, 1997). The work refuses the individualism that medical interventions prescribe by connecting his experience to his family – sickle cell is an inherited disease that largely affects people of African, Caribbean, Mediterranean, Middle Eastern and Asian ancestry.

In hospital, the medicalised body is made vulnerable, each part imaged by scientific equipment: X-ray, scan, ultrasound. In Rodney’s work, like Britannia Hospital (1989), these technologies are used to visualise the intersection of racialised and medical violence. From bed, Rodney worked in oil pastels on X-rays, which could then be put together to form largescale portraits. Beyond drawing on medical imaging technologies (sometimes literally), Rodney also made the hospital a gathering place for his close-knit group of friends and artists. Autoicon, the last work in the Whitechapel exhibition, was finished by his friends after his death, and his partner also enabled his art practice and its legacy through her care. Interdependency is part of the work, as it is part of all our lives.

Not all support systems are supportive – some work to suppress. 1880 THAT: Christine Sun Kim and Thomas Mader, which recently opened at the Wellcome Collection, also in London, refers to the year of the first international conference of deaf educators, held in Milan, during which a group of mainly hearing people agreed to suppress sign language and Deaf culture in favour of speaking and lipreading. Kim and Mader memorialise the conference and the stigmatising consequences of oralism in sculpture, film and installation. The patronising act of ‘looking down your nose’ is reversed and literalised, made ridiculous, as a suspended sculpture asks you to Look Up My Nose (2025). An red inflatable nylon arm (ATTENTION, 2022), waving as it inflates and deflates, points at a damaged wall – hoping, perhaps fruitlessly, that we’ll notice. Meanwhile Zines Forever! DIY Publishing and Disability Justice, also on view at the Wellcome, displays zines created by disabled zine-makers. With titles like ‘Bed Zine’ and ‘thoughts on crip value in a capitalist land’, the collection presents artmaking as a way of creating and maintaining community and mutual support. (You can read the zines in the bed provided, with up to three other people.) Some of the zines reckon with the disability benefits system, such as ‘My First PIP Assessment’ and ‘Sick note culture’. ‘Will we ever see justice for sanctions, deaths and institutional violence towards disabled people from austere UK Governments?’ asks @HiddenInkChild, whose zines explore ableism from a sick and trans masculine perspective.

Accessibility is built into these exhibitions, which visitors can access using audio description, British Sign Language video guides, relaxed openings and visual stories available online. Much of the work of making art institutions more accessible continues to be facilitated by artists themselves with largely unpaid labour. Following their hugely influential essay ‘Sick Woman Theory’, Johanna Hedva was inundated with invitations from art institutions to participate in events, as these spaces looked to trade on Hedva’s cultural capital with little to no consideration of accessibility. In response, Hedva began the process of using an ‘Access Rider’, a document outlining their access needs. ‘At best, it has meant that I’ve served as a learning experience I did not particularly want, nor was I paid, to be,’ Hedva writes in How to Tell When We Will Die: On Pain, Disability, and Doom (2024), a book that defies, as they put it, the sick memoir genre editors wanted them to write ten years ago. ‘Worse, I’ve been ignored, argued with, chastised for being difficult, and disinvited because of that document.’ For Hedva, accessibility is part of a revolutionary proposal of ‘all-out institutional change’. They call for disability access to be seen as the political movement it is, and ableism as ‘the most integral component of all oppressive ideologies’, from white supremacy to transphobia. In their solo show at TINA in London last year, works on paper were pinned to the walls by large knives, while blown glass sculptures dripped black goo from their vulvalike lips onto the carpet – they were angry, uncontainable.

In 2022–23, an estimated 16.1 million people in the UK had a disability – 24 percent of the total population. Most people will be disabled at some point in their life. And if there’s one salient point from the work presented across multiple institutions this spring, it’s this: disability is not a separate category of personhood. Welfare is one way of recognising that everyone has needs, that all of us live interdependently rather than independently. Individualism – and by extension the falsehood that some of us don’t want to be well, don’t want to work, don’t want to get better, don’t want to overcome our limitations, but also, principally, that some of us don’t need anything from the state or each other – is a capitalist myth that creates the conditions for dispassion and profit. A person who needs support is less of a person; they are a drain, a burden. These art practices do not treat the illness experience, or the d/Deaf experience, or the disabled experience, as something unique and separate. It would be incorrect to assume their work defies their physical limitations. Disability is not something to overcome – and it is not a choice. We must resist the systems of oppression we all suffer under, together.

Alice Hattrick (they/them) is the author of Ill Feelings (Fitzcarraldo Editions) and the coproducer of Access Docs for Artists, made in collaboration with Leah Clements and the late Lizzy Rose