A new collective is taking aim at the ‘institutional ableism’ of the artworld

“We’ve exhausted a lot of nice strategies – there’s nothing left but just telling the truth about what it’s like to be a disabled artist.” Edinburgh-based writer and performer Harry Josephine Giles is angry and determined; angry about the way those with disabilities are so often shut out of the contemporary artworld, and determined that something is done about it. “These extraordinary times are particularly isolating and dangerous for disabled people,” they continue, “but the anger and frustration is also because we’ve had decades of consultations looking at why disabled people aren’t represented in the arts. We’re sick of saying the same things over and over again. There’s consultation fatigue.”

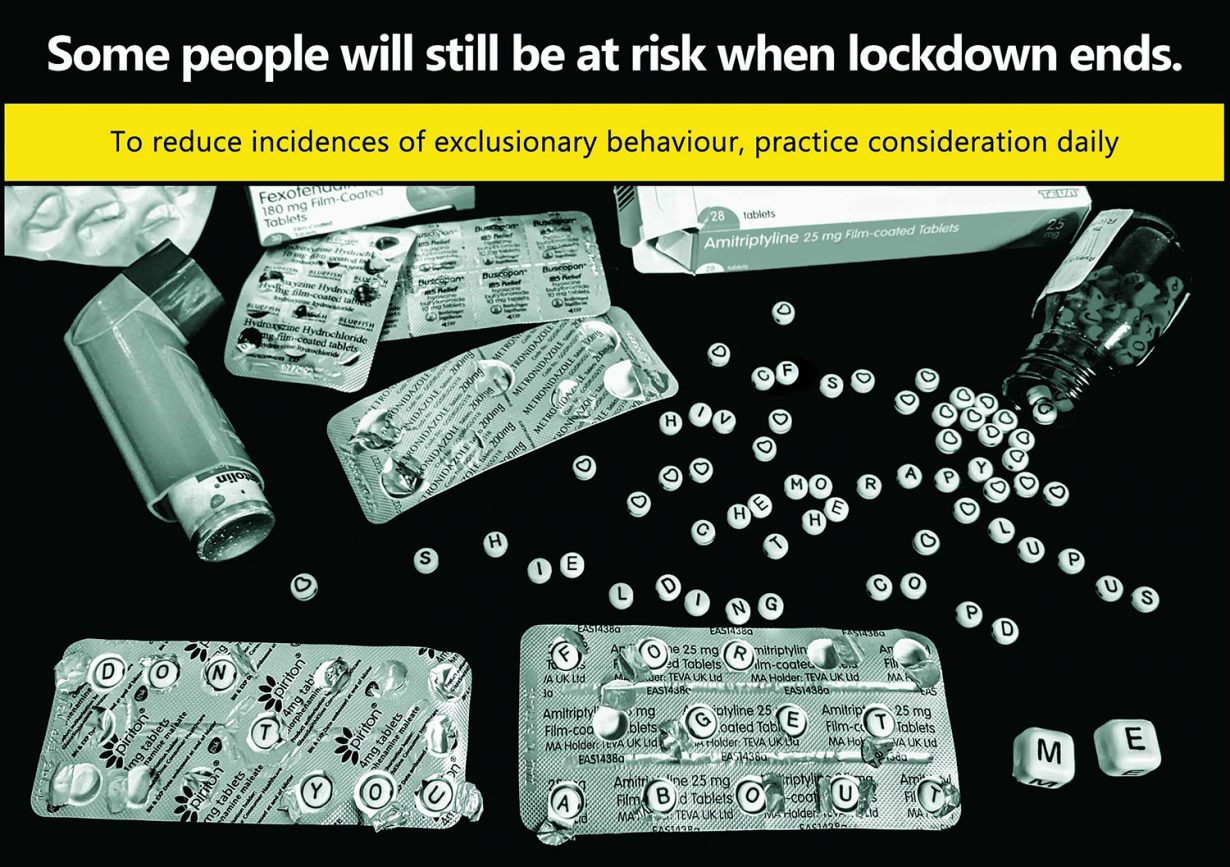

With digital artist and campaigner Sasha Saben Callaghan, Giles is the curator of Not Going Back To Normal, a ‘collective disabled artists’ manifesto’ featuring contributions from more than 45 artists. Conceived during the first COVID-19 lockdown, the project’s name is a riposte to the notion that a return to a pre-pandemic ‘normal’ is desirable for the disabled. As the original call for contributions puts it: ‘Before COVID-19, disabled artists were already routinely excluded from visual arts and galleries, were already often failed by the arts and cultural sector […] Normal was already no use to us, and we were never normal.’

Commissioned by a group of Scottish galleries and visual arts organisations including Edinburgh’s Collective (which has acted as producer), CCA in Glasgow and Arika (one of this year’s Turner Bursaries recipients), Not Going Back To Normal exists as an online gallery of artworks, texts and provocations. For the most part, these are shot through with fury at what is described as the ‘institutional ableism’ of the visual arts. Giles characterises the artworld’s funding system as premised on artists competing with each other for commissions, exhibitions, residencies and prizes. It’s a system, they believe, that many artists with disabilities are unable to navigate due to the physical and mental barriers inherent in an arts infrastructure built by the non-disabled. The collective approach of the manifesto project is, they say, a provocation in of itself, offering an alternative to this default position of “making artists compete with each other for small pots of money”.

“The curatorial approach was about including as much as possible rather than filtering a selection,” explains Giles. “So in a way it was the reverse of a normal open call – it wasn’t a question of let’s get this out and judge people, it was about making enough people feel supported and welcomed into doing this so that we can get the broadest diversity of perspectives.” Contributors range from widely exhibited artists such as Alec Finlay and Simon Yuill, to those who are yet to have an exhibition. What comes through vividly in the varied contributions is the messy and sometimes brutal everyday reality of living with a disability while trying to develop an art practice. Queer, chronically ill photographer Chris Belous writes about the ‘punishment’ of the benefits system – ‘Fighting for cash saps your energy and time – what’s left after a day listening to DWP hold music?’ – while Vince Laws’s artworks take a defiant, uncompromising stance: ‘If the System Cripples You, You Must Cripple the System’, announces one spray-painted A2 poster. These and other artists’ works feel raw, personal – they are telling, not asking.

While the artists who have contributed to Not Going Back to Normal are all Scotland-based or have strong links to the country, the issues they face are clearly replicated globally. In the US, for example, United States Artists has recently announced the Disability Futures Fellows, funded by the Ford Foundation and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, providing USD$1 million in grants to 20 practitioners over an 18-month period. Brooklyn-based multimedia artist Navild (niv) Acosta was one of the recipients. He told ArtReview that the award “feels like justice”. Asked about the wider significance of the initiative – which is billed as ‘the only national, multidisciplinary award for disabled artists and creative practitioners’ – he said: “It will likely take a lot more initiatives modelled after this one to carry much significance on a global scale… I can only hope it’s the very beginning of a change.”

In the UK, initiatives such as the disability arts commissioning programme Unlimited have continued to commission new works during the pandemic, and offer a route to funding for disabled artists – including some of those who have contributed to Not Going Back to Normal. What the manifesto proposes, though, is a more fundamental shake-up, rather than a system that mirrors the artworld’s existing commissioning structures. In their introductory text, titled ‘Creating the Impossible World’, Giles and Callaghan list five key demands, including that Creative Scotland – which has funded the project – should be ‘proactively seeking out disabled/D/deaf and neurodiverse artists to invest in, work with, and lead in its management and Board’, and that any organisation it funds should ‘demonstrate clearly how they will work accessibly’ while ensuring that its ‘workforce, commissioned artists, community participants and audiences’ should be at least 20 percent disabled (in line with the UK’s working age population). “The problem [for disabled people] is that we can’t afford to be artists,” Giles tells me. “We need an approach to arts funding that prioritises work that is happening at a grassroots level; work that is always more inventive, more productive, more diverse, more inclusive. There’s no top-down solution; there’s only a bottom-up solution.”