A reflection on the speculative potential of integrated access

The social model of disability says that what disables people are the barriers in society, not their impairment or difference. In the arts, disability access is often dealt with in practical terms, box-ticking the list of basic needs that a public space should cover – ramps, disabled toilets, lifts, corridor widths, light levels and hanging heights – but the scope of accessibility extends beyond physical adjustments and delves into the nuanced realm of communication. Access is also the translation of sensory experiences from the visual art into language, audio or text and vice-versa. The terms ‘integrated access’, ‘embedded access’ and ‘creative access adjustments’ are all variations on the notion that disability access can play a creative role in exhibition-making rather than an afterthought.

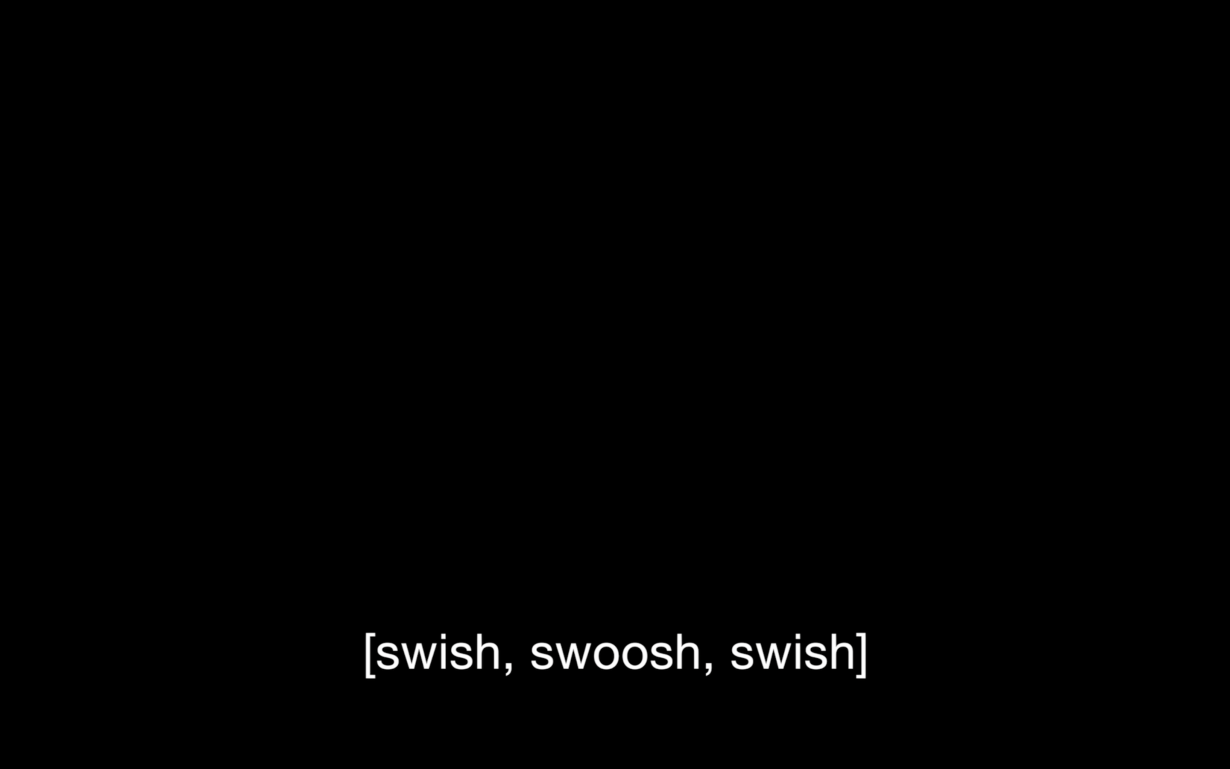

In Long Take, which opened at the ICA Philadelphia in 2023 and then travelled to Nottingham Contemporary, artist Carolyn Lazard addressed the relationship of the camera with dance by displaying a blank film with only sound and closed captions describing an audio track of a moving body and choreography instructions. Removing the visual element of the film questions sight as a primary means of aesthetic experience. This small shift challenges ableist notions of film and opens a can of conceptual worms, spurring something deeper about the gaze, the fetishised body and the right to opacity.

This is disability access as material, and many artists – like Lazard, Leah Clements, Park McArthur and Jessa Mockridge, to name a few – are moulding it to open up their practice beyond the realms of disability. Rather than treating captions, image descriptions, audio transcripts or plain text as accommodations, they see them as language-based materials to be explored.

As a curator working within a feminist ethical framework, I am interested in how this kind of approach to access might lead to a curatorial methodology that is ground-breaking for all. In a recent episode of the podcast ‘Curating Tools’, Sean Lee, curator at Toronto non-profit Tangled Art + Disability, discussed Yinka Shonibare’s 2007 statement during the London Disability Arts Forum debate at Tate Modern, where the artist asserted that ‘the disability arts movement is the last avant-garde’, succeeding feminism, queer and the Black arts. For me, intersectionality in the arts means trying to take down barriers and supporting not only diverse artists but also diverse audiences.

This curatorial method follows artists, who have been collaborating, self-organising and programming in ways that create a crip community and new vocabulary. ‘Crip’ is used by individuals to reclaim a position as disabled, sick or neurodivergent and in the domains of art and theory indicates an intersection with race, class and gender. Artist Jamila Prowse has been instrumental in bringing to view crip artists and access adjustments by leading workshops, writing and curating events, including ‘Hyper Functional, Ultra Healthy’ at Somerset House last year. Others advocate for disability access by providing practical resources that change the way the industry works. Take, for example, Lazard’s online accessibility guide ‘A Promise and a Practice’, which lists access adjustments for institutions; Leah Clements, Alice Hatrick and Lizzy Rose’s ‘Access Docs for Artists’, a rider how-to for artists and art workers; or curator Iaraith Ní Fheorais’s newly launched ‘Access Toolkit for Artworkers’, a comprehensive step-by-step to inclusive exhibition making. These documents are not just about requesting essential needs, they articulate crip dreams for improved communication and access intimacy – that elusive sensation when someone truly understands your access needs, as defined by writer Mia Mingus.

Last year at South Kiosk, London, I curated INSOMNIA, an exhibition of Leah Clements’s photography accompanied by image descriptions read out loud and played in the gallery in surround sound. The image descriptions (a textual aid for VIP/blind and neurodivergent individuals) were written by Clements in a poetic language to set an atmosphere that evoked the emotional and psychological impacts of insomnia-related sleep phenomena and sleep paralysis. Clements followed a proposition by artists Bojana Coklyat and Finnegan Shannon called ‘Alt-Text as Poetry’, where simply writing the alt-text (image descriptions used for back-end website metadata) with care and thought ‘shifts the process’. Clements builds on this to develop a process she called re-weirding where, instead of clarifying what is in the image, she used language to make the work more ambiguous, creating an atmosphere of paranoia like the kind that tricks our perception in the middle of the night. The recorded voice said things like ‘We can’t distinguish their face, but we know they’re about to look at us. A promise or a threat, something is about to happen.’ With advice from visually impaired performer Ebony Rose Dark and vocals by sound artist Vivienne Griffin, Clements created a work that guided visitors around the space, aiding abled and disabled people alike while heightening the eeriness of the show.

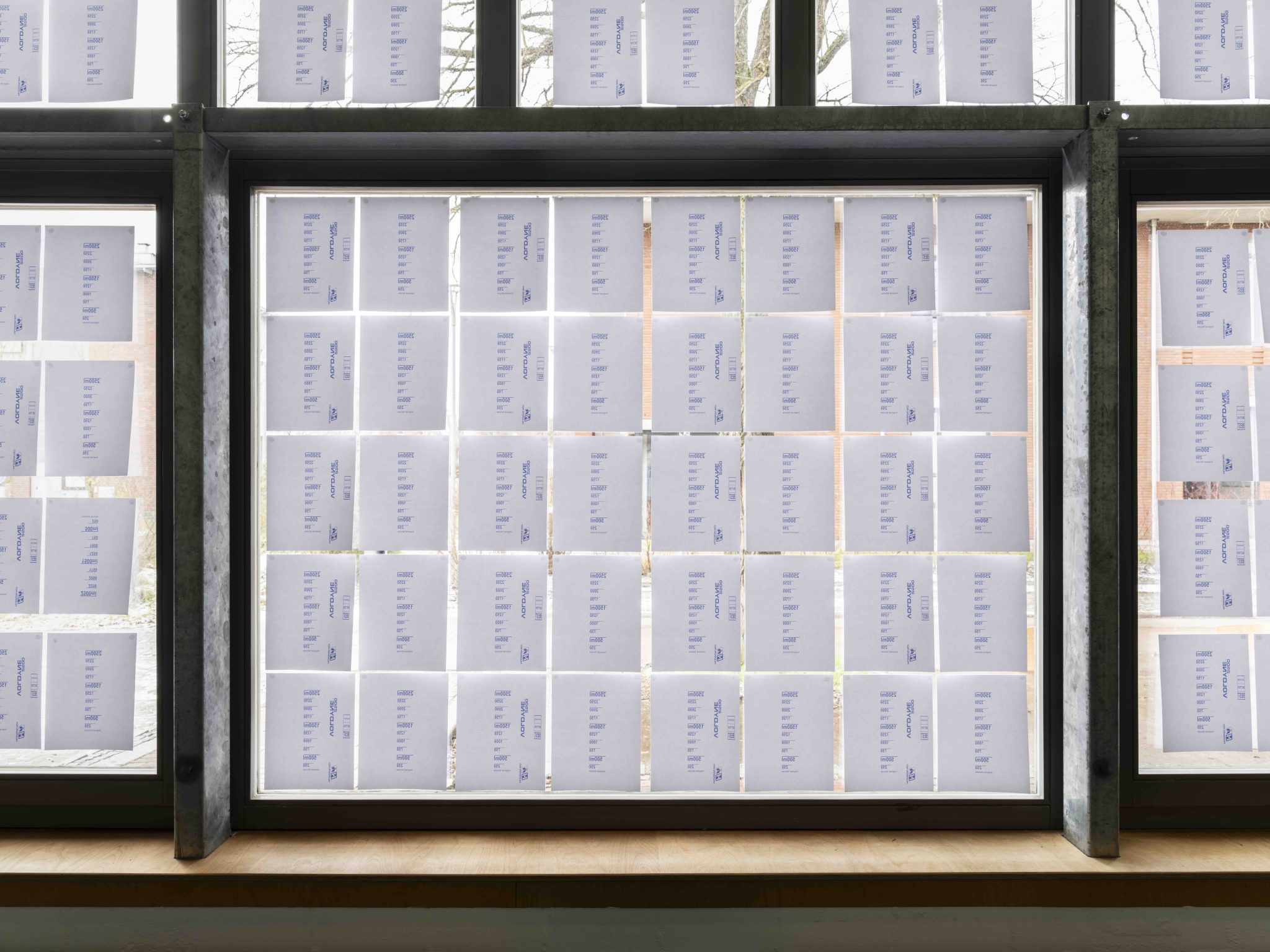

In keeping with Clements’s approach, McArthur’s current exhibition Twice at the Kunstraum Leuphana in Lüneburg examines the power of language-based transcription and description in a poetic and dramatic way. Developed with MA students from Leuphana University, the work descriptions in the show were written from the perspective of a visitor. Made for remote viewing over Zoom, the narrative transports the audience to the icy grounds of the university, conveying each embodied detail: ‘I move carefully, as it is slippery. … I breathe in the ice-cold air. When I breathe out, a small cloud appears. Both my body and the air flowing out of my lungs are warmer than all that surrounds me.’ The narrator’s voice serves the function of both a press release and a tour guide, but more than describing a corporeal experience of the exhibition, the artist and students employed this writing method to coax an awareness of breathing, introducing viewers to the exhibition’s central theme.

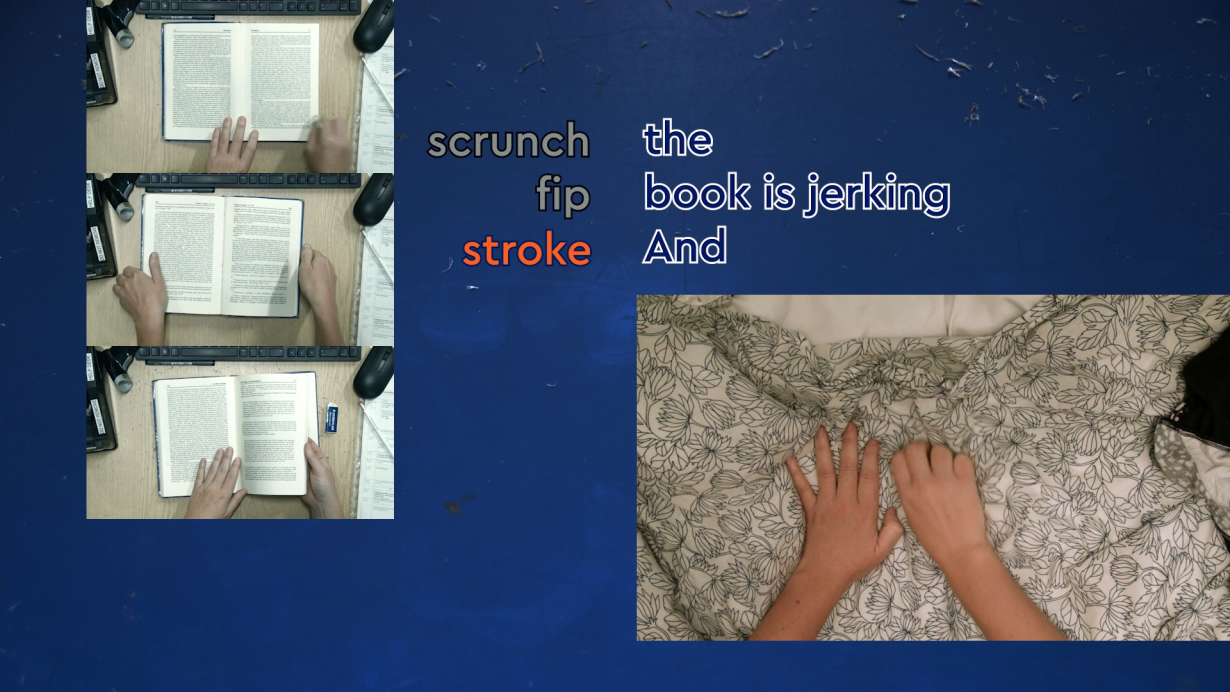

Expanding on the textuality of access, artist Jessa Mockridge draws on Laura Marks’s theory of ‘seeing as touching’, suggesting that in film the eye behaves like an organ of touch. Spivak_rub (2024) depicts a librarian’s hands rubbing out pencil marks in a well-worn copy of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s 1987 book In Other Worlds. Erasing these collective annotations is required for the digitisation of books for anyone who can’t access the library physically or who relies on screen readers. Spivak_rub dwells on the attachment readers feel towards those marks, diving into a fantasy about the previous reader, and increasingly sexualising the librarian’s gestures. She rubs, thumps, scrapes and jerks to the rhythm of animated captions that read ‘fip, fip, fip, flip, pinch, and stroke’, which quiver in time with the sound of her movements. Halfway through, the book is replaced by bedsheets but the hand motions and sounds continue. The text takes central space in the image and muddles up the senses, words for gestures are listed as audio descriptions; narrative spills over into the transcriptions; ‘She sounds tired but chatty’ is read but not heard. Mockridge received feedback from Collective Text, a disabled and Deaf artist-led organisation providing integrated and creative access. Like Clements, Mockridge found that practical adjustments can be creative not despite restrictions but because of them.

Thoughtful engagement with access takes time. The current setup for exhibitions frequently focuses on immediacy, presence and embodiment, primarily through visual experiences tied to institutional constraints and embedded ableism. Despite these conditions, artists like Clements, Lazard, McArthur and Mockridge engage in material experiences that are creative and sensorially inclusive. Curating is inherently concerned with the relationship between art and its public. Disability access, with its speculative potential for deepened and expansive experiences, should be a central focus.

Mariana Lemos is an independent curator from Lisbon based in London