A new look at the history of drag promotes a deeper understanding of sex and gender in Britain

The time-honoured artform of drag is reaching audiences like never before – the 2022 Netflix hit series Queen was made in Poland, currently the worst-ranking country in the EU in which to be LGBTI, which demonstrates the power of post-RuPaul enthusiasm for all things drag. As such, this academically rigorous yet very readable book should draw readers – especially considering that the UK, which consistently topped Rainbow Europe’s index of LGBTI-friendly countries until 2015, has dropped to 17th place, with antitrans rhetoric and long waits for gender-affirming care listed as reasons.

But those seeking an all-encompassing survey of British drag might be disappointed. Jacob Bloomfield sets some parameters early, focusing on male performance – on stage, screen, radio and record – between 1870 and 1970. He proposes that during this era ‘female impersonators’ (as such performers were once called) cannot be squarely understood through present-day characterisations of drag as a transgressive, queer artform; a turn that Bloomfield dates to the Stonewall riots of 1969, or closer to home, the ‘radical drag’ of the British Gay Liberation Front, established in 1970. Rather, by shining a spotlight on popular cross-dressing revues by ex-servicemen of the interwar period, or summoning the once ubiquitous figure of Danny La Rue (a glamourous darling of Royal Variety performances who, in one critic’s words, did ‘not have the menace of a freak’ and who frequently played to conservative mores), Bloomfield illustrates how drag has long been a complex yet ‘ordinary’ artform, historically straddling queer radicalism and mass entertainment along the way. The question is whether ‘ordinary’ is ever that simple.

It’s a question that seemed frequently to flummox state censors at the Lord Chamberlain’s Office. Some of their hilariously prudish comments could easily fall from the pages of a mid-twentieth-century social satire; a choice quote by one employee finds him so flustered by ‘the eternal subject of sexual intercourse’ he wishes ‘God had not created Man and Woman but thought of something else!’ – to which an arch queer response might be, ‘Quite!’. But the evidence shows that ‘respectable’ audiences ‘with great enthusiasm’ for drag-based entertainment have always outweighed a loud handful of conservative fundamentalists, such as those currently protesting ‘Drag Queen Story Hour’ events at venues across the country – including London’s Tate Britain. Despite the niggle of persistent anxieties, drag seems to have largely benefited from a rather British sense of insouciance about its ‘threat’, though to trust this would be a fool’s game.

As Bloomfield points out, much contemporary drag rejects the binary that ‘female impersonation’ suggests, but ‘even the most abstract forms of present day drag… prod spectators to consider gender’. The book wrestles with figures from drag’s history who now feel uncomfortably retrogressive, such as La Rue, who was apparently so keen to dismiss the label of ‘drag’ and assert his masculinity that a New York Times reporter described him as ‘a man impersonating a man impersonating a woman’. These figures are hugely significant to understanding the British relationship to sex and gender, and the ways in which its society has and continues to transverse the spectrum. Bloomfield advocates for this with notable attention to the British class system. If ever there were a nation that thrived on nostalgia, polite eccentricity and giggling over sex, it is, for better or worse, the UK, and Arthur Lucan, as ‘Old Mother Riley’, understood this completely. Where La Rue was the court jester playing to Middle England, Bloomfield hails Lucan for energising the figure of the ‘dame’ with comedic, emotional complexity and rallying his working-class audience as he took on the establishment in films such as Old Mother Riley, MP (1939). He argues that while Lucan was an ostensibly heterosexual cis man performing a regressive stereotype, he nevertheless brought Old Mother Riley’s womanhood, age and Irish ethnicity to the fore in a joyful, ‘unruly’ way that freed her from society’s conventions and restrictions, and to which his audience could crucially relate. A figure such as Lucan, derided as ‘lowbrow’ by both Tory politicians and the cultural elite, should not slip so easily from the queer lens. Bloomfield’s book is peppered with delicious quotes that nudge such ideas along, and one from La Rue is perhaps key to the book’s message; when a master of artifice declares, ‘I admire message theatre, but I haven’t got any messages’, trust that there is more to know.

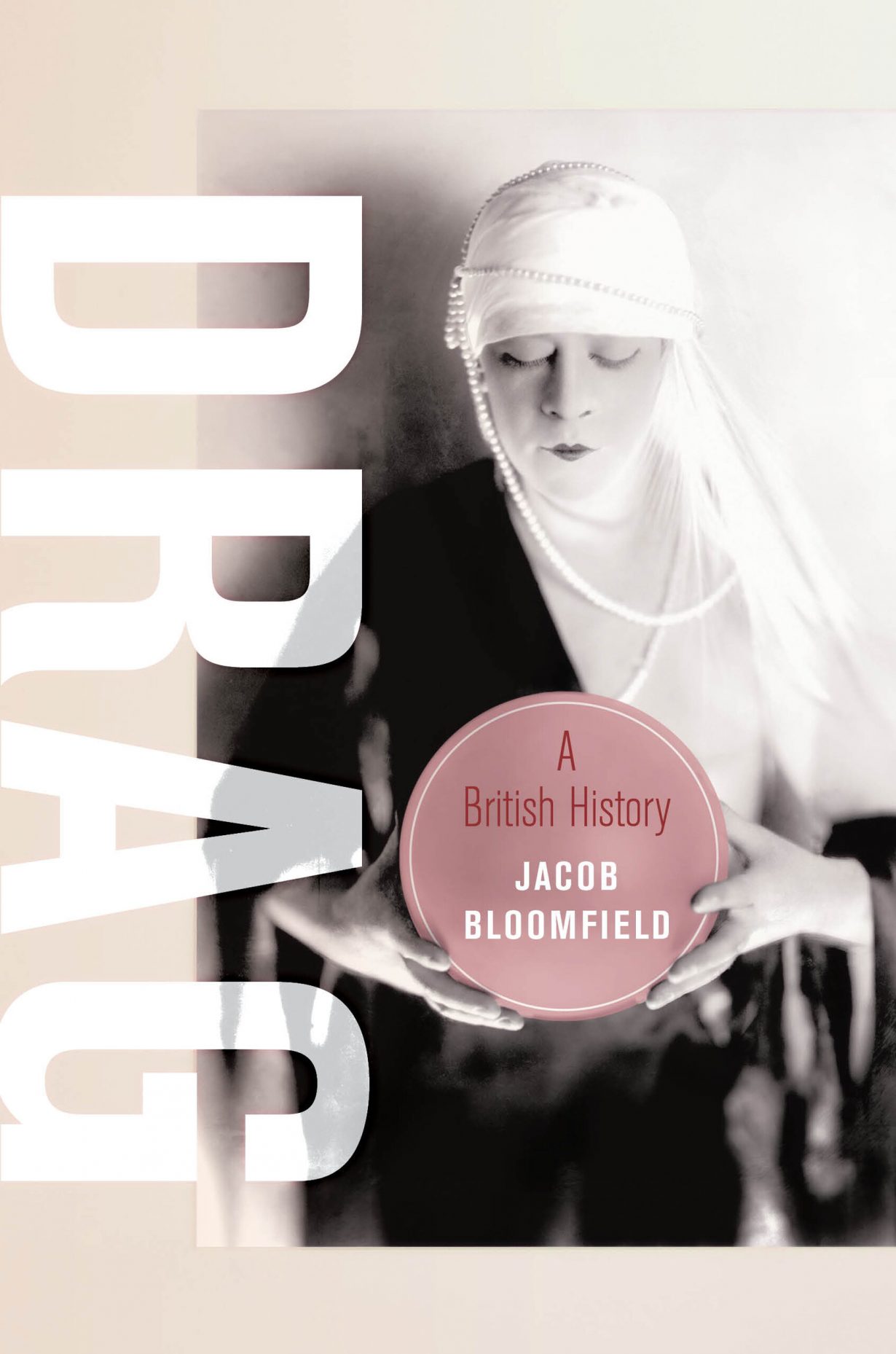

Drag: A British History by Jacob Bloomfield. University of California Press, £25 (hardcover)