Eschewing the trappings of biographical fixation, a recent retrospective narrates the formal development of the artist

The work of the African American abstract painter Ed Clark, who died in 2019, emerged out of, and then outlasted, an era in which art was concerned with its own historical development. Today, the dominant approach to writing about and curating art is to focus on biography, understood both as cause of, and interpretative framework for, an artist’s oeuvre. Eschewing this outlook, this retrospective produces a narrative of its subject’s formal development, told confidently but sparingly in a succession of rooms dedicated to different periods in the artist’s career. On each canvas Clark grapples with the constraint that he imposed on himself when, in 1956 in a loft in Montparnasse, he adopted the push broom as his preferred instrument for applying paint on a canvas.

It was in Paris that he encountered the work of the Russian-born painter Nicolas de Staël who was, alongside Cézanne, Clark’s greatest influence. What he seemed to have admired in de Staël, who produced images of footballers made up of thick strokes in which the bristles of the brush were legible, was the idea that the singular movement of a mark made on a canvas could become the subject of a painting. This is a possibility that Blacklash (1964), one of Clark’s early experiments with the broom, reveals to be exhilarating and terrifying. A bloodred block frames the left side of the canvas, producing an ominous sense of order. Running parallel is a black block, which juts out in a stream of tentacular lines. Some spit out reds and oranges, the product, perhaps, of flicks of paint from a broom suddenly halted. The combination of these elements is a bravura performance: Clark manages to depict frenzied, almost slap-dash, movements alongside lines made with the precision of a laser pen.

That this necessitated placing the canvas on the floor, Jackson Pollock-style, meant that his paintings had, in his words, an element of physicality. But this was an element that Clark sought to restrain, almost as if he were leaning on the brush and pulling himself away from it at the same time. In Locomotion (1963), Clark moves between two modes of using the tool: in the top left corner, delicate lines separate turquoise and black. On other sections of the canvas, bright oranges, blues and greens – dragged along by the sheer speed of the painter’s movement – blur atop a white underlayer visible beneath the thin paint.

Although Clark hung out in the same bars as Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko, he was a relative latecomer to Abstract Expressionism: Pollock died in 1956 and five years later critic Clement Greenberg was already giving talks with titles like ‘After Abstract Expressionism’. A movement that even its acolytes proclaimed to have been running on fumes by the 1950s would perhaps seem irrelevant today. But what makes this show compelling is its attention to the internal variety within a genre often understood to be monolithic.

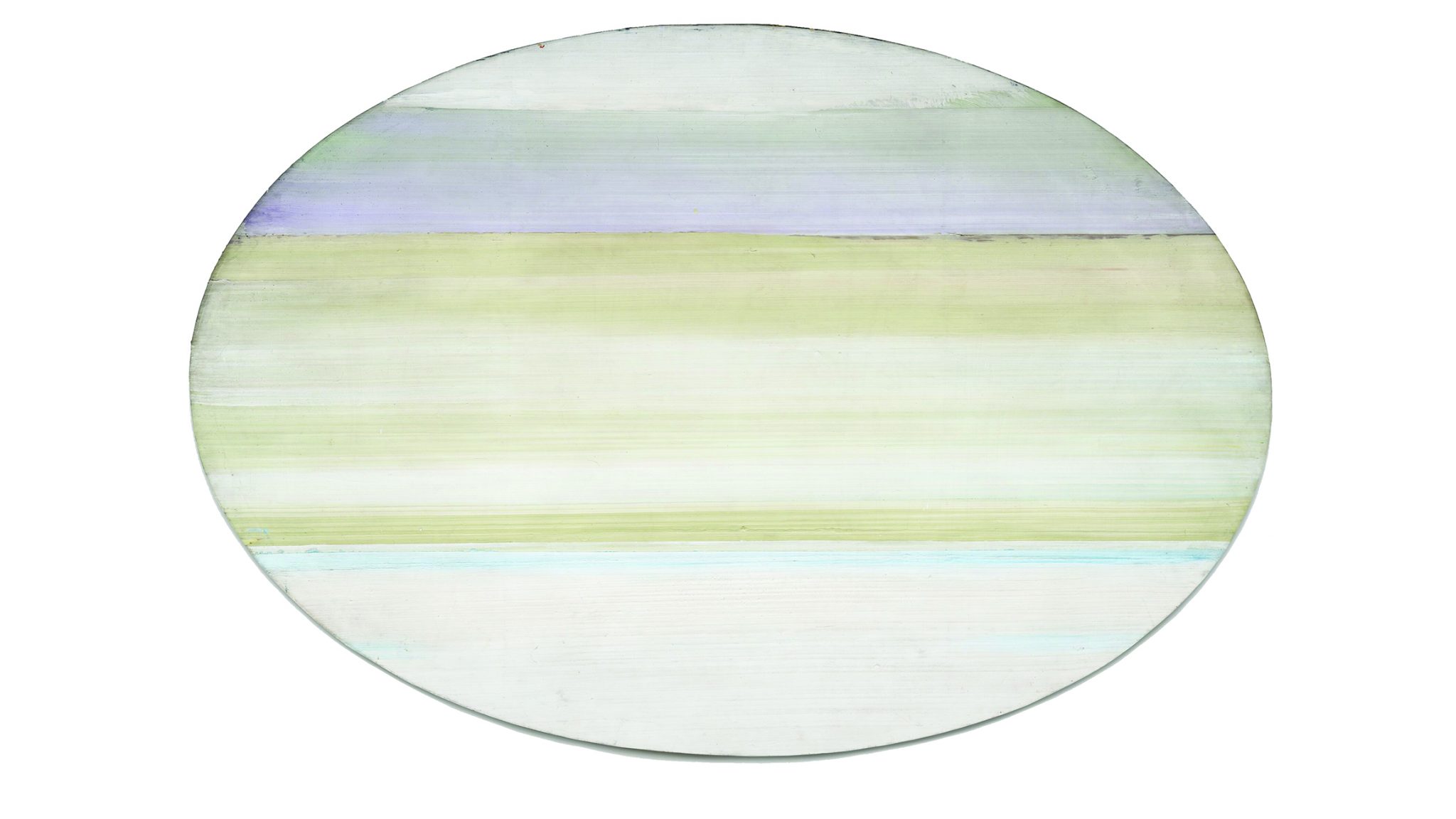

In the subsequent rooms, the use of the broom to create rough violent patterns with paint and the play with the canvas’s shape – as in the irregular shaped Untitled (1957) – was supplanted by more controlled compositions and conventional canvases. The paintings that represent Clark’s output from the 1970s to early 80s, most of which were completed in New York, are exemplary here. Ife Rose (1974) and Blue Umber (1975) both show the artist attempting to insert control and precision back into his work more forcefully than in previous paintings. It is as if in a battle between the dominant forces in his art, a Cézannesque sense for colour and a de Staël-influenced painterliness, the former has won out. In Ife Rose, precise horizontal lines constrain his brushstrokes, and in Blue Umber he adds to these an internal oval frame. The effect of this more regimented style is to focus the viewer’s attention firmly on colour, which when combined with horizontal lines appear to be zooming past like multicoloured cables seen from the window of the tube. The period of wild experimentation turns out to have been an interregnum, followed by geometrically precise paintings still completed with the broom but in a spirit closer to Piet Mondrian than Helen Frankenthaler. This is a story free from the biographical drama prevalent within discussion of postwar art, but this show is all the better for it.

Ed Clark at Turner Contemporary, Margate, 25 May – 1 September