Electric Dreams at Tate Modern reinterprets art at the dawn of the digital explosion as a harbinger for our current moment

Many visitors to Electric Dreams will have no recollection of society, or art, before the internet; before global content platforms, the mediating of opinion by social media algorithms and the virtualisation of physical experiences by VR. Others, like this writer, can recall the appearance of home computers, David Hockney experimenting with a Quantel Paintbox on TV and a first email account at art school. Either way, the recent wave of art-and-science and computer-art survey shows touches some cultural nerve: not just in serving up millennial retro-fascination for outdated tech and yesteryear culture, but reinterpreting this art as the precursor and harbinger of our current moment, in which technology and the network seem conclusively to have taken over.

There’s something to be said for reading history backwards like this. What were once discrete movements and moments – Op art, Kinetic art, Computer art, environments, happenings, video art and what used to be called ‘intermedia’ – Electric Dreams assembles as a four-decade runup to the digital explosion of the late 1990s. What comes through most is the complicated, contradicted enthusiasms among artists for two major themes – technology as a utopian enabler of human communication, and technologically produced art as a generator of new aesthetic experience, liberating art from the chains of its archaic forms and genres.

It’s fair to say that many of these artists were ahead of their time in their thinking, even if, where the show picks up in the 1950s, the technology was clunky. It opens with archival photographs of Atsuko Tanaka wearing her extraordinary Electric Dress (1956, reconstructed 1999), a robe made of tangled flex alight with dozens of incandescent coloured lightbulbs and tubelights, which Tanaka made while a member of the Japanese Gutai group. Produced as Japan’s postwar reconstruction gathered pace, and drawing out Gutai’s almost spiritual attachment to ideas of abstraction, matter and energy, the dress (or at least its documentation) hangs here as if anticipating every cyborg fantasy to come, not least in the hallucinatory biomechanoid sci-fi that Japan would produce by the 1980s.

Not far away is work by Op and Kinetic artists who emerged in Europe at the same time as Gutai, notably the West German Zero group. Here are those handbuilt machines made of motors, lights, Fresnel glass and other products of modern manufacture, made by artists who, from Europe to Asia to Latin America, shared similar visions of art as a dynamic noncontemplative experience, tuned to the new technological society. A standout here is Otto Piene’s installation Light Room (Jena) (2005/2017), a reprise of his 1959 Archaic Light Ballet; a disorienting choreography of shifting patterns of bright dots wheeling across the dark walls, projected from rudimentary lightboxes on the floor. A cosmic spectacle generated from little more than punctured hardboard and 60-watt bulbs, Piene’s room presaged the increasingly delusional futurism of the light-and-motion art that would grip the 1960s. Although that spectacularism slipped out of favour in art during the 1970s and 80s, it’s not hard to see it resurrected with a cultural vengeance in the form of ‘immersive art experiences’.

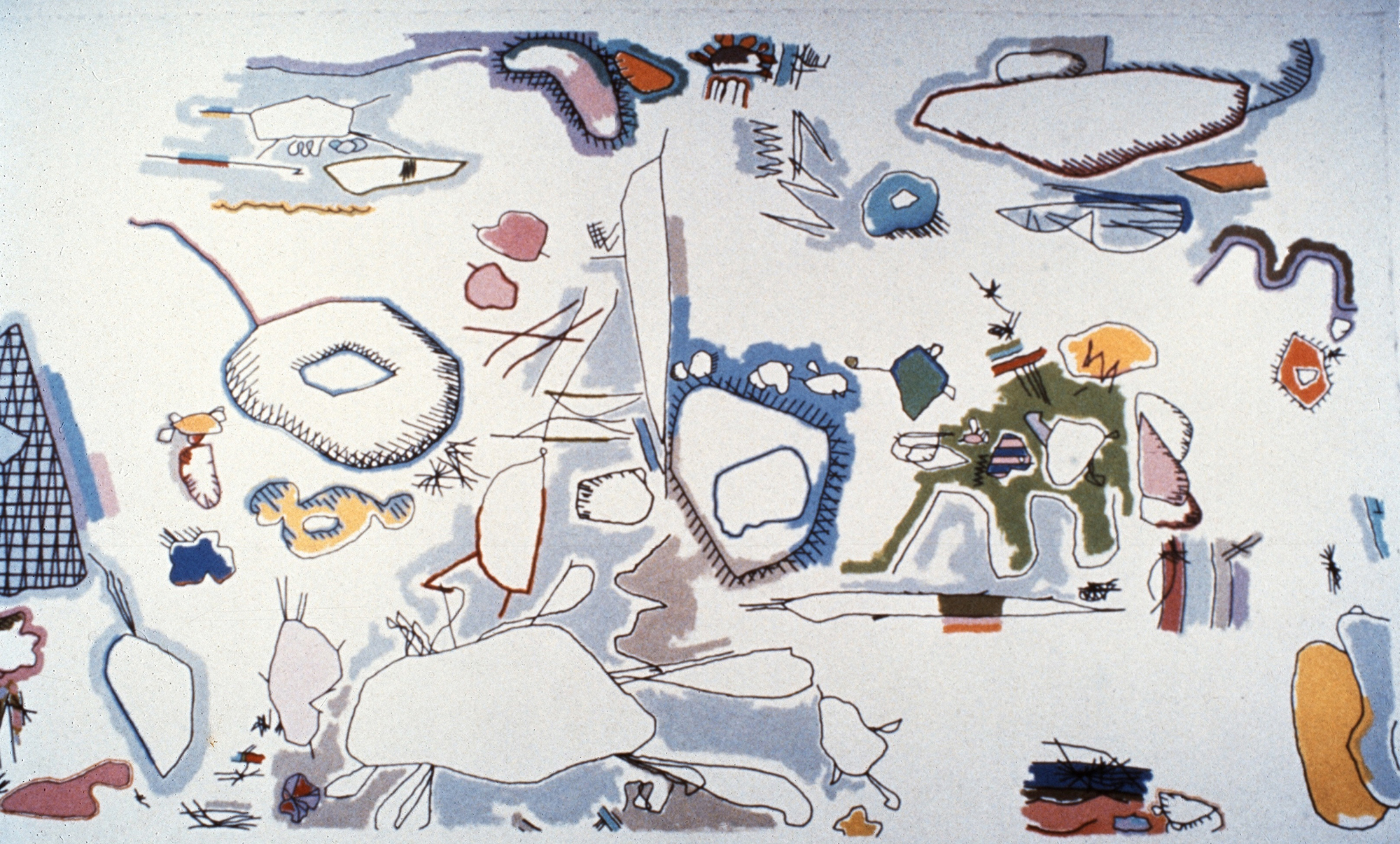

If the Op and Kinetic bubble popped along with the radical optimism of media-theorist Marshall McLuhan’s concept of a global village and the stalled revolutions of May 1968, the arrival of accessible computing during the 1970s spurred a new generation of artists to try to get the machines to make work, triggering a wave of plotter-drawn art, epitomised by Vera Molnár’s austere grids of increasingly disordered concentric squares (Transformations 1–21, 1976). Abstract painter Harold Cohen, for his part, spent his later years teaching his AARON program to draw. The peculiarly organic, floating coloured blobs on the huge canvas of AARON #1 Drawing (1979) suggest something of the lasting paradox of trying to make machines ‘see’ like humans, and how, post-Google DeepDream, machine vision relates to artificial intelligence.

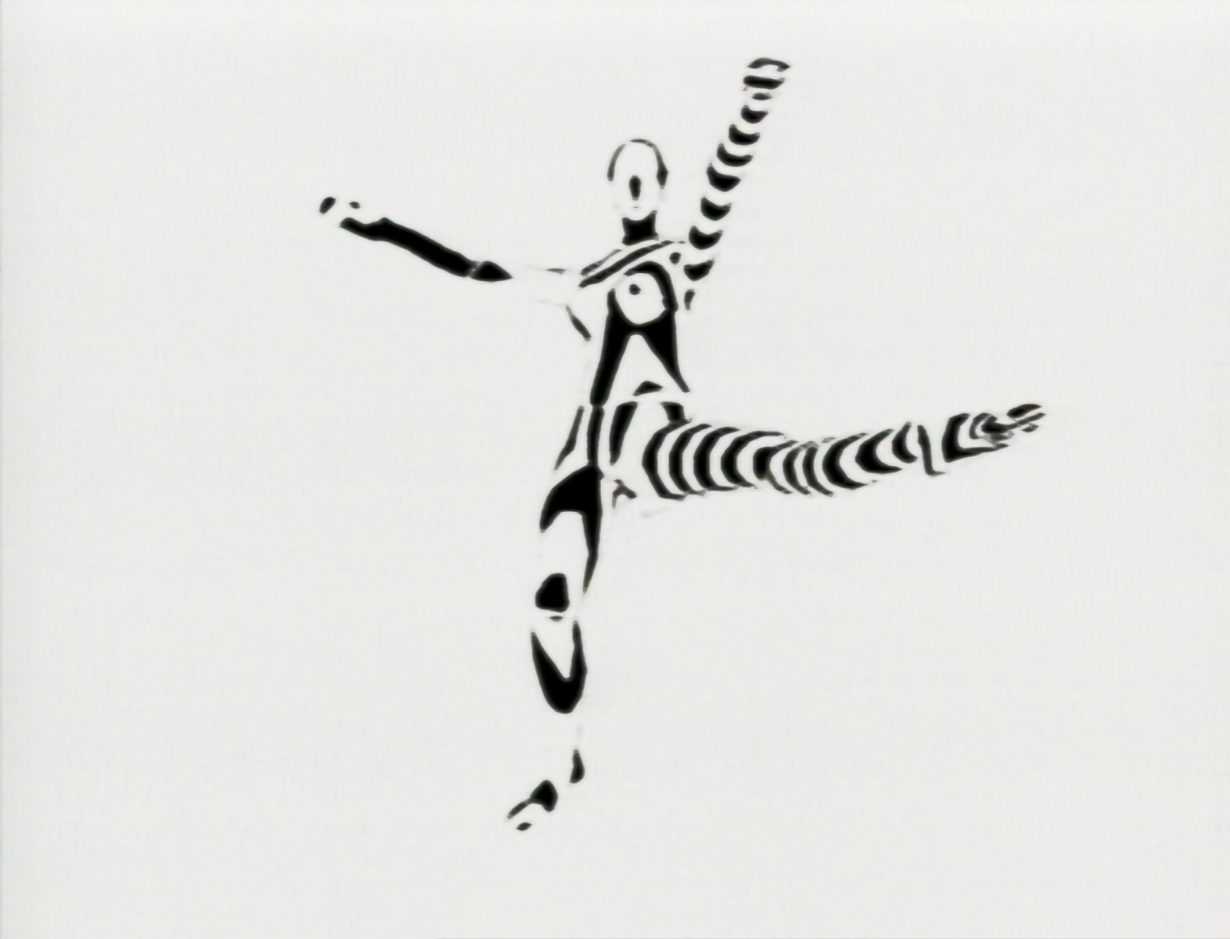

Where Electric Dreams starts to move into the era of a more recognisably contemporary digital culture, though, the stakes seem to be lower, as the technology becomes more capable and at once more banal. By the 1980s artists were advocating visual technologies that would eventually outrun them; Rebecca Allen’s CGI animation of a dancer’s movements (Steps, 1982) is elegant, but, along with her iconic album-cover graphics and animation for the band Kraftwerk, there’s a downbeat intimation here; that visual artists would soon have to confront the corporate juggernauts of the MTV media-era, and decide whether to take on visual technology as an adversary or an enabler. As the 1990s arrive, we find ourselves in the meditative, aloof, cod-spiritual darkness of Tatsuo Miyajima’s LED installations, his patterns of illuminated counters quietly winking through numbers 1 to 9 (Lattice B, 1990) – art no longer heralding the revolutionary fusion of aesthetics, technology and society, but rather offering a refuge from a culture in which aesthetic technology had become a form of power and control. (It’s worth noting a number of odd curatorial omissions: no LED ticker works by Jenny Holzer; the absence of Gustav Metzger’s trippy 1965 Liquid Crystal Environment; and nothing by the influential British artist-apostle of cybernetics Roy Ascott).

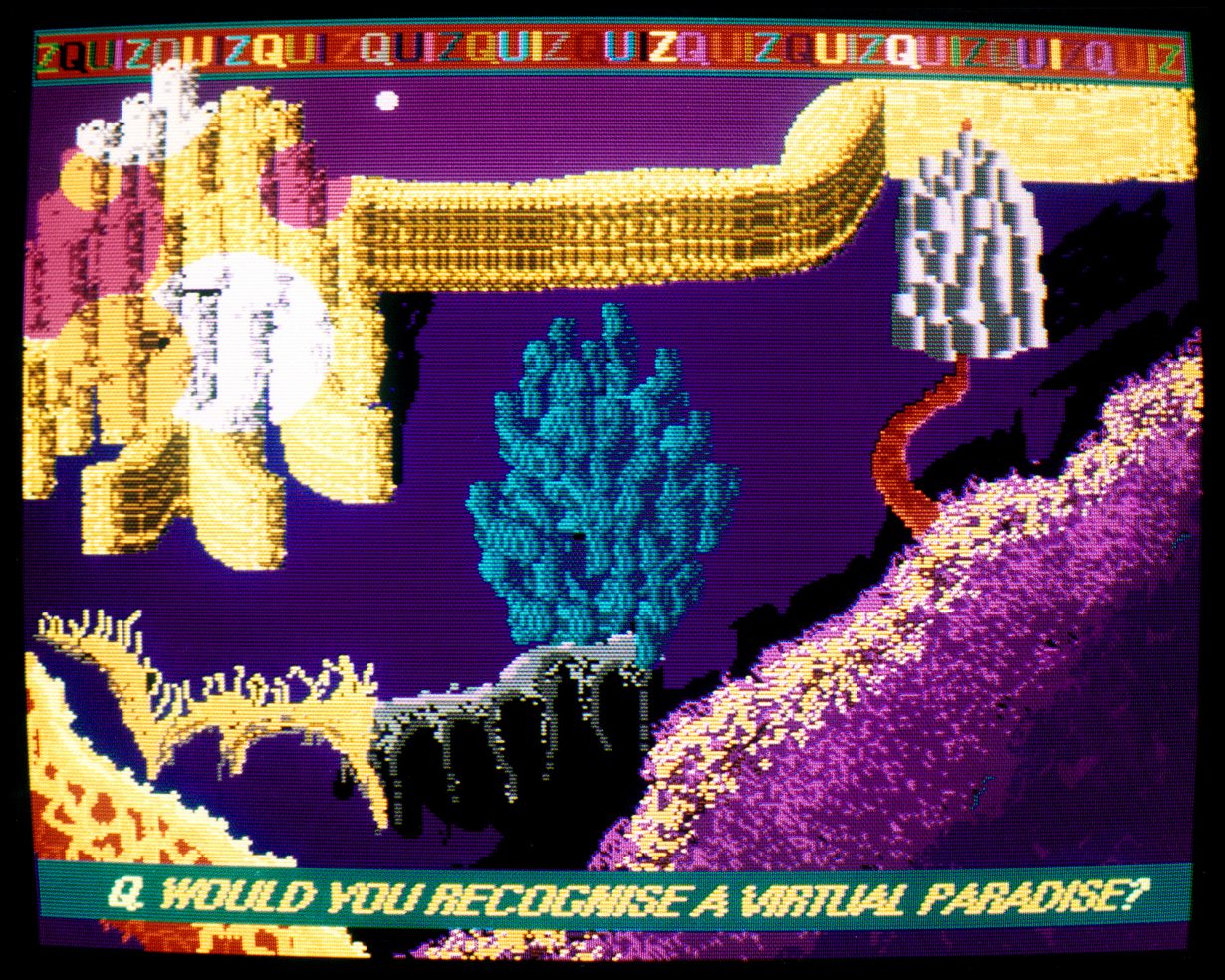

But the 1990s nevertheless produced artists hacking the ascendant digital culture, playing its absurdities back on itself; Suzanne Treister’s Fictional Videogame Stills (1991–92), photographs shown on Sony monitors, apparently cobbled together on her Amiga 1000, ape the lurid, 16-bit aesthetic of choose-your-own-adventure videogames. Above a pixelated landscape of a rutted path leading to a tree on the horizon, with an odd pink snakelike form running across it, is the question ‘Are You Dreaming?’ Another, a glitchy scene of what looks like a world of strange underwater corals, has a banner wondering, ‘Would you recognise a virtual paradise?’ They’re questions as pertinent today as in 1992, even if – in the era of AR headsets, AI generated art, drone swarms and the global panopticons and echo chambers of Big Tech – we’re in still less of a position to know what the answers might be.

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet at Tate Modern, London, through 1 June

From the January & February 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.