“Understanding how to communicate with a dog and get in the mind of a dog has taught me a lot about empathy… And that bleeds into a lot of things”

Upon entering the exhibition Crip Time at Frankfurt’s Museum für Moderne Kunst in 2021, visitors immediately found themselves between two sculpted lifesize dogs standing on their hindlegs facing each other, paws outstretched. Seeming to be frozen in action, the animals looked like they could step or spring towards each other – or the viewer – at any moment; visitors navigated the space according to the dogs’ placements.

The work is called Dancing with London (2021) and was created with polystyrene foam, Celluclay and epoxy putty by New York-based artist Emilie L. Gossiaux with exactly this intention: “When I make sculptures,” she says, “I think about the choreography of them in relation to how the viewers will approach and interact with the work.” Beyond their positioning with the audience, the sculptures also represent the daily choreography between Gossiaux and her guide dog: London is a recurring visual motif in her practice, and, for the past ten years, has been a constant companion in her life.

Since Gossiaux lost her vision in an accident in 2010, she and London have built a relationship that the artist described earlier this year in The Paris Review as being ‘like a marriage’. Although her sculptures, drawings and paintings prior to 2020 explored interpersonal relationships through the lens of memories and dreams, nary a human – aside from herself and her partner, Kirby – has been seen in her work since then. Rather, she now translates her and Kirby’s kinships with London to visually explore the potential of interspecies relationships: what humans can learn from animals and how to think about our existence from an anti- Anthropocentric perspective.

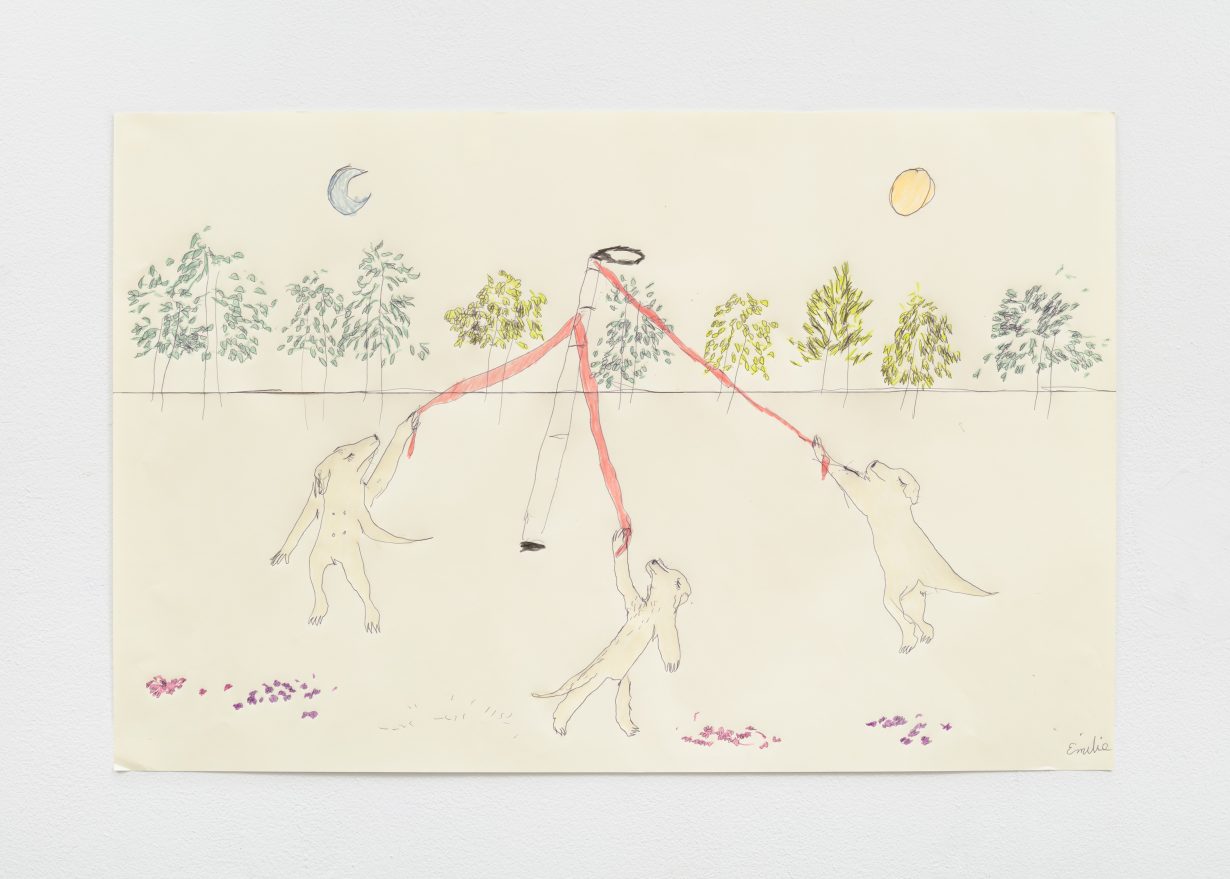

When I call Gossiaux, who received her BFA from Cooper Union, New York, and MFA in sculpture from Yale, New Haven, she is preparing for her first institutional solo exhibition, at the Queens Museum in New York. The show, opening later this year and titled Other-Worlding, will revolve around The Whitecane Maypole Dance (2023), an installation that, she explains, will feature “three lifesize Londons dancing on their hindlegs holding onto ribbons that are dog leashes attached to a maypole, which I drew to resemble my white cane. They are in a valley with trees behind them. In the sky, a sun and a crescent moon hang side by side.” Before talking about the symbiology in the installation, which is based on her drawing London, Midsummer 1 (2022), we go back to the beginning: why London features so prominently in her work, Gossiaux’s decision to leave the human figure largely behind in favour of creating “super-beings” and how she adjusted her practice after losing her vision.

The Human-Animal World

In works like The Valley of Magic (2018), a line drawing showing the butts of two naked people who are lying side by side on their stomachs, Gossiaux explored interpersonal relationships. “Since I lost my vision, I always had this longing for community,” she says. She also explored community by way of collective memory: in recreating Botticelli’s Birth of Venus in a 2018 diptych painting of the same name, “I was playing with people’s memories of recognising something, and my memory too,” she says. But during grad school her practice shifted away from interpersonal relations and towards interspecies relationships. It was at this time that Gossiaux “first started to consider how deeply important my relationship with London is”. So, I ask, what made you start to consider your relationship with London in an artistic way?

“In New Haven, being in a new place with new people, there was a feeling of isolation, and London became a constant. In my apartment my bed was close to the ground, so London would walk up onto the bed every night. I would wake up with her head on my hips, my shoulders or the same pillow next to me. I was craving that kind of closeness and intimacy, and I really began to appreciate London as a person.”

But then, in 2018, London got sick: she began losing teeth and bleeding in the gums; a vet found tumours growing in her mouth. When waiting for the biopsy results (they were negative), Gossiaux remembers, “I couldn’t even talk on the phone I was crying so hard. It was difficult to imagine and understand London’s mortality – it hit me like when you’re a kid and think about death for the first time and realise it happens to everyone. This was the first time I realised how much she meant to me, and what not having a companion would be like. That’s when I began to draw in my sketchbook these memories of us dancing together: when we came home from the studio at night, London and I would dance together in the apartment.”

Shortly thereafter Gossiaux made her first Dancing with London sculpture, based on one of those drawings from her sketchbook, and London has frequently appeared dancing ever since. Why is London almost always seen dancing?

“There’s something about an animal walking upright, to me, that is very significant,” Gossiaux says. “I talk about hierarchies in relationships between animals and humans, and breaking down that hierarchy or at least blurring it, so that the animals and humans are both walking upright. So, it’s about London having that movement, that action, of dancing and being so free. That’s also how I think about dancing personally: I love dancing. That freedom of movement is really significant to me.”

From then on, her subjects oscillated between the animal and human worlds, with works like the 2019 series E. L. G. Familial Archives (Outerspace) exploring familial relationships and memories by way of sculpting body parts in clay and inscribing them with her tattoos, her dad’s and her sister’s as she remembers them. But come 2020, she and Kirby became the only two humans to be depicted – and always with an animal. Was it a conscious decision to leave other human figures behind?

“It did become a conscious decision, especially during the pandemic. Prepandemic, London had grown used to me sometimes going out without her, so when all of a sudden Kirby and I rarely left the house, the connection between us became more intense. Also, going back to nature, I would have dreams of being outside with London in forests, among trees and dirt and grass, the sky and the bugs, and it created a sensation of longing. London, as an animal, drew me closer to that feeling of longing, that imagination and that dreamworld.”

In the ten years you’ve been together, how has your relationship with London affected your understanding or perception of the world?

“Since London and I first met, I have begun to understand the animal world more. Sometimes I put myself in her perspective or in her body, trying to understand what it’s like to be a dog or an animal; to get in tune with her pleasures and desires. Understanding how to communicate with a dog and get in the mind of a dog has taught me a lot about empathy – instead of getting frustrated, I empathise. And that bleeds into a lot of things, like empathy for other people and other relationships.”

Creating ‘Super-Beings’

Being in sync with the animal world led Gossiaux to create what she called “super-beings” in an interview with Platform. One such example is her 2021 sculpture True Love Will Find You in the End: comprising two figures holding hands, one figure has London’s body and Gossiaux’s head; on the other, the body parts are reversed. “I morphed our bodies together as a self-portrait,” she says. “When I had this idea, I had just read Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation [2017], by Sunaura Taylor. It felt like [it encompassed] everything I had been thinking about with my relationship to London, with the animal world more generally and with nature.”

What really stood out to you in the book?

“The chapter that has stuck with me most is about circus performers at the beginning of the twentieth century. The performers had disabled or disfigured bodies with physicalities similar to animals – like seal arms or chicken feathers, or skin that looked like an alligator’s. Instead of feeling exploited, the performers embraced their identities and loved being on display; it was a joyous experience. That’s interesting to me, because when I walk around with London, she becomes part of my identity as well. It’s like, ‘When Emilie shows up, you can expect London will be at the party too.’ But I don’t think about myself or my relationship with London as ‘I’m dependent on the dog’, or ‘the dog is leading me’. That I’m wholly dependent on the dog for getting around is a misconception that people have about a guide dog and a handler’s working relationship with each other, and this misconception takes away my sense of agency.

“So, I started to think, ‘Is this how people see me?’ And at the same time I started to really appreciate Sunaura talking about how, when she was younger, she would pretend to be a dog and bark at strangers; how she always wanted to be an animal, and that we are all animals fundamentally. After I read that book, I started to think about other aspects of my identity that I share with animals.”

The following year, Gossiaux created Alligatorgirl (2022), a series of drawings and sculptures merging human figures with alligators. Did Sunaura’s book also inspire your Alligatorgirl works?

“Yes, but that character came from a lot of different things. I’m from New Orleans, and across the street from my house was a canal where I often saw alligators. I loved going there and getting really close to the water to look at the turtles and alligators. The alligator then gained new significance after Hurricane Ida in 2021, when I read articles about alligators moving freely around the suburbs because there was so much water. There was one really big alligator and officials found the remains of a man inside it.

“At the same time, I was also thinking about climate change and the ways humans have continuously destroyed natural habitats through deforestation and building homes and cities around forests, swamps and wetlands. For better or for worse – obviously for worse – the alligators are becoming closer to human environments. I’ve read other stories where people are completely ignorant of that, and they interact with alligators in dumb ways. It’s like, ‘It’s your fault you got eaten by an alligator.’

So, my sculpture Alligatorgirl has a human face inside an alligator’s mouth and it’s like, ‘Did she eat the human? Or are the human and the alligator becoming a single being?’ It’s dark, but that’s my sense of humour.”

A Tactile Process

Gossiaux’s working process, primarily with drawing and sculpture, relies on tactility. She draws with ballpoint pen on an instrument called a Sensational Blackboard, which raises the lines as she draws so she can feel the image in real time; she then colours the raised-line drawings with Crayola crayons – which are organised in envelopes with braille labels to indicate colours – due to their waxy surfaces. But this wasn’t always the case. How has your drawing practice changed over the years?

“Drawing used to be a struggle for me,” Gossiaux says. “I really did not like drawing classes in high school, but I loved printmaking and etching. Drawing in that way, with just one line, became a lot clearer. So, when I got to Cooper [Union], before I lost my vision, I developed my style by making cartoony and kind of childish line drawings. That became a practice I enjoyed for myself – I could be on a tiny page in a little world and draw cartoony. When I lost my vision, I struggled to find that satisfaction in drawing again. I didn’t get it until I picked up the Sensational Blackboard, pen and paper – that was around 2018, and it clicked instantly. Drawing in that way allows me to draw the way I’ve always drawn in my sketchbooks.”

Ceramics only entered her practice after she attended a class in Minneapolis, while she was at BLIND, Incorporated, which she describes as a “kind of bootcamp for blind people to get their independence back”. Why did you start working with clay?

“I had always hesitated to work with clay because I thought of the medium as having limitations, or that classes would be about making teapots and mugs. But I took a class in Minnesota anyway, and I had a great teacher who was very perceptive when I wanted to make sculptures of animals and body parts – and then it clicked.” It clicked not only because of a helpful teacher but also because Gossiaux found that elements of working with clay related to painterly processes – and before losing her vision, painting was her “thing”, she recalls. “With painting, if I didn’t like it, I could paint over it or wipe it out,” she explains. “And with clay, if I didn’t like it,” she says, “I could start over or I could amend it.”

Were there other similarities you experienced between the mediums?

“There are also wonderful painting techniques that can be applied to the surface of clay, and I hadn’t thought about colour in a long time. Colour, to me, in sculpture was not important. But using colour in clay made it more of a sculptural technique than a craft or technical skill. And I don’t think of myself as being technically skilled in clay – it’s something I approach as a sculpture or a painting.”

London, Midsummer

Returning to her forthcoming exhibition, we’ve already addressed London dancing, so, I ask, what’s the significance of midsummer?

“The maypole and midsummer dance are a celebration of summer, which has its own symbiology as a celebration of femininity, or the maiden’s dance. And personally I think of femininity, the divine and nature as being connected. When thinking about nature, I also think of London, because I feel more connected to nature and the animal world through her. This also leads me to autonomy and agency: London is my guide dog; she gives me autonomy, and so does my white cane.

“So, with this installation, and three drawings that will also be on view, I am thinking about London and the birth of summer as a celebration of femininity and nature. I have taken the midsummer maypole icon as my own, turning it into a white cane, and the three Londons dancing as a symbol of freedom. It’s about London’s agency and my freedom of movement.”

Other-Worlding is on show at the Queens Museum, New York, through 7 April 2024