The exhibition puts ideas of memory and reality in conversation with the recent, earthquake-hit history of the Italian city

Shapes that remain in the visual field after intense light hits, or as the result of contemplating an image too long: these optical illusions ostensibly give Afterimage its title, but this 26-artist group show – held at the recently opened branch of Rome’s MAXXI museum in the Abruzzo region – isn’t centred on the visual per se. ‘Afterimage’, here, refers to a trace of an event that persists enough to trigger an emotional coda, settle a memory or give time to rationalise. An afterimage is also an alienating moment of superimposition between a memory momentarily imprinted in the retina and the surrounding reality. The balance between an event’s strength, persistence and transience allows this exhibition to call into question, indirectly, the recent history of the city of L’Aquila, the region’s capital hit by a tragic earthquake in 2009 – a terrible wound followed by a tiring and not yet completed period of social, economic and urban reconstruction.

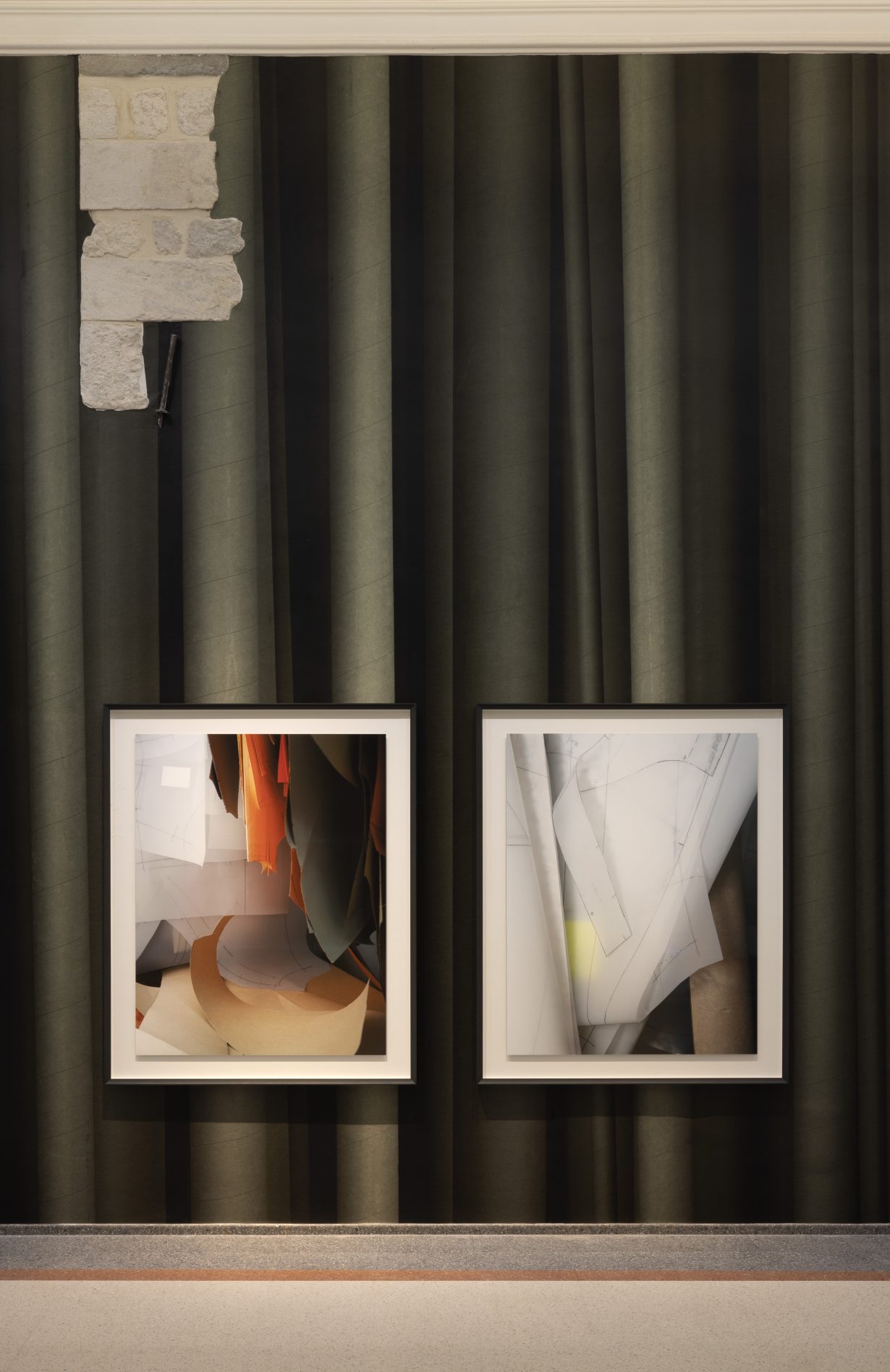

The restored palace that houses the museum, Palazzo Ardinghelli, is a notable example of the local late baroque, sitting on previous Renaissance constructions lost in a previous earthquake in 1703, though the exhibition’s curators, Bartolomeo Pietromarchi and Alessandro Rabottini, avoid turning this echo into a ‘theme’ to burden the multiple suggestions elicited by the concept in the works. In extracts from Ana Miletić’s Materials series (2015–), for example, the show’s theme of transformative resilience takes the form of handwoven textiles based on photo- graphed acts of repair in urban space (roofing, fencing, wrapping) taken in Zagreb and Sisak after earthquakes that occurred in 2020; Benni Bosetto transfers memories from collective history in the installation Saturniidae (2022) – large iron necklaces hanging from the walls that refers to a craft tradition of producing auspicious toy amulets for infants; Stefano Arienti has transformed photographs of the surrounding mountain landscape into tapestry through a digital process that destroys the original image to give it a second life; Thomas Demand, in a permutation of his long-running Model Studies series (2011–), focuses on the paper patterns the late French-Tunisian fashion designer Azzedine Alaïa used to construct his influential garments and pushes the archival material toward a seductive geometric abstraction.

In other cases, the overlap between past and present is conveyed through practices that cross historically distinct technologies of representation (such as Frida Orupabo’s representations of bodies collaged from colonial image archives, or Mario Schifano’s ‘Inventario (Inventory)’ series from the early 1970s, in which he transposed television images onto photosensitive emulsion on canvas, adding details with enamel paint). But Afterimage is not a nostalgic show – the state of constant change is invoked as an instrument producing the present and the future: as with the carousel of mutated creatures inside iPads in Massimo Grimaldi’s Scarecrows (2021–22), or in the hybrid figures captured in the process of remixing in Pietro Roccasalva’s The Skeleton Key II (2007) and Marisa Merz’s Untitled (2009–10). Or, more openly, He Xiangyu’s Asian Boy (2019–20) a pensive, underdressed and hunched sculpture that, in context, suggests the titular youth facing, alone, untold futures and possibilities.

Afterimage resonates with meditations central to the histories of art: the technologies of representation (photography, audio recording) that have often served as a challenge to the passage of memory and time; the role of the modern(ist) artist in dialoguing with, distilling and analysing – more or less critically – what surrounds them (as in the words of Charles Baudelaire: ‘Modernity is the transitory, fugitive, contingent; it is but one half of art, of which the other half is the eternal and immutable’); and the long-debated status of the museum as an institution that determines what enters a stable ‘history’. It’s tempting to imagine one Latin-speaking poet as the (occult) inspiration of the exhibition: Ovid, born less than 40 miles from L’Aquila, who, in his major work The Metamorphoses (8 AD), handed down and renewed many classical myths, influencing future generations, infecting them with awe and wonder, and making transformation itself his protagonist.

Afterimage at MAXXI – L’Aquila, through 19 February