From Black beauty and feminine power to the spirit of the Haitian Revolution and the return of Stranger Things, our editors on what they’re looking forward to this month

Feminine power: the divine to the demonic

The British Museum, London, 19 May – 25 September

Historically, while women have often lacked power (social, political), feminine archetypes of power are an enduring presence in world mythologies. Iconographies of eroticism and temptation, as much as nature, nurture and care, have for centuries accrued in the image of women. Meanwhile, contemporary culture is more mixed up than ever about how men and women should negotiate questions of power and empowerment, and whether feminine and masculine even define what men and women are. So the British Museum’s Feminine power: the divine to the demonic presents a timely – and likely hotly debated – survey of artefacts and artworks representing ‘female spiritual beings in world belief and mythological traditions around the globe’. With the current gender wars and the latest attacks on womens’ reproductive rights in the US, it’s unlikely Feminine Power will be received as a neutral, even-handed take on bygone cultures. J.J. Charlesworth

BLACK VENUS, curated by Aindrea Emelife

Fotografiska, New York, 13 May – 28 August

In the early nineteenth century, Saartjie Baartman, an enslaved woman from the nomadic Khoekoe group of southwestern Africa, was brought from the then-Dutch colony of South Africa to London and put on display in ‘freak shows’ organised by Alexander Dunlop and Hendrik Cesars. She was exhibited in private wealthy homes as well as public fairs around other parts of England and in Limerick, Ireland, in 1812, because of her steatopygic body-type – one that resonates with the form of the Paleolithic-era Venus figurines. For this, she was nicknamed the ‘Hottentot Venus’, her body turned into caricature as much as it was racialised, fetishised and dehumanised. Baartman died in Paris in 1815, having been exhibited in further shows across Europe and used as a subject of scientific racism. Her remains were on display in Paris’s Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle until 1974. Her story is the catalyst for BLACK VENUS, an exhibition by 17 artists whose works celebrate Black beauty, reclaim Black womanhood, and highlight the layered and nuanced narratives of Black lives today. Contemporary works by artists from around the world including Tabita Rezaire, Zanele Muholi, Kara Walker, Deana Lawson, Widline Cadet and Amber Pinkerton, will be shown in dialogue – and interrogation – with archival depictions and representations of Black women dating back to 1793. Curated by art historian and writer Aindrea Emelife, BLACK VENUS invites visitors to confront the long history of racial and sexual objectification of Black women’s bodies: ‘By looking at early images, we identify the beginning of the othering of Black women. In a contemporary age, where Black women are finally being allowed to claim agency over the way their own image is seen, it is important to track how we have reached this moment.’ Fi Churchman

Stranger Things 4

Netflix, vol.1 streaming 27 May

Probably one of the last few reasons why I haven’t cancelled my Netflix subscription yet, the fourth season of Stranger Things will be released at the end of this month (only the first five episodes, the further four coming out 1 July) and based on the trailer, it’s about to get even more apocalyptic. The show’s brilliance from the start has been its schizophrenic lacing of teen-bonding and ’80s Americana nostalgia with conspiracy theories, aliens and doomsday horror. Yet the former has given ground to the latter with each new season. In Season 3 a shopping mall opened in town; evil Soviets tried to open a portal to the Upside Down; there was a strange case of possessed rats and missing fertiliser; and the Mind Flayer’s power over the town of Hawkins grew stronger, taking over more and more hosts to do his bidding. With a reported budget that exceeds that of Game of Thrones and The Mandalorian combined, Stranger Things 4 promises to be nothing if not spectacular. Louise Darblay

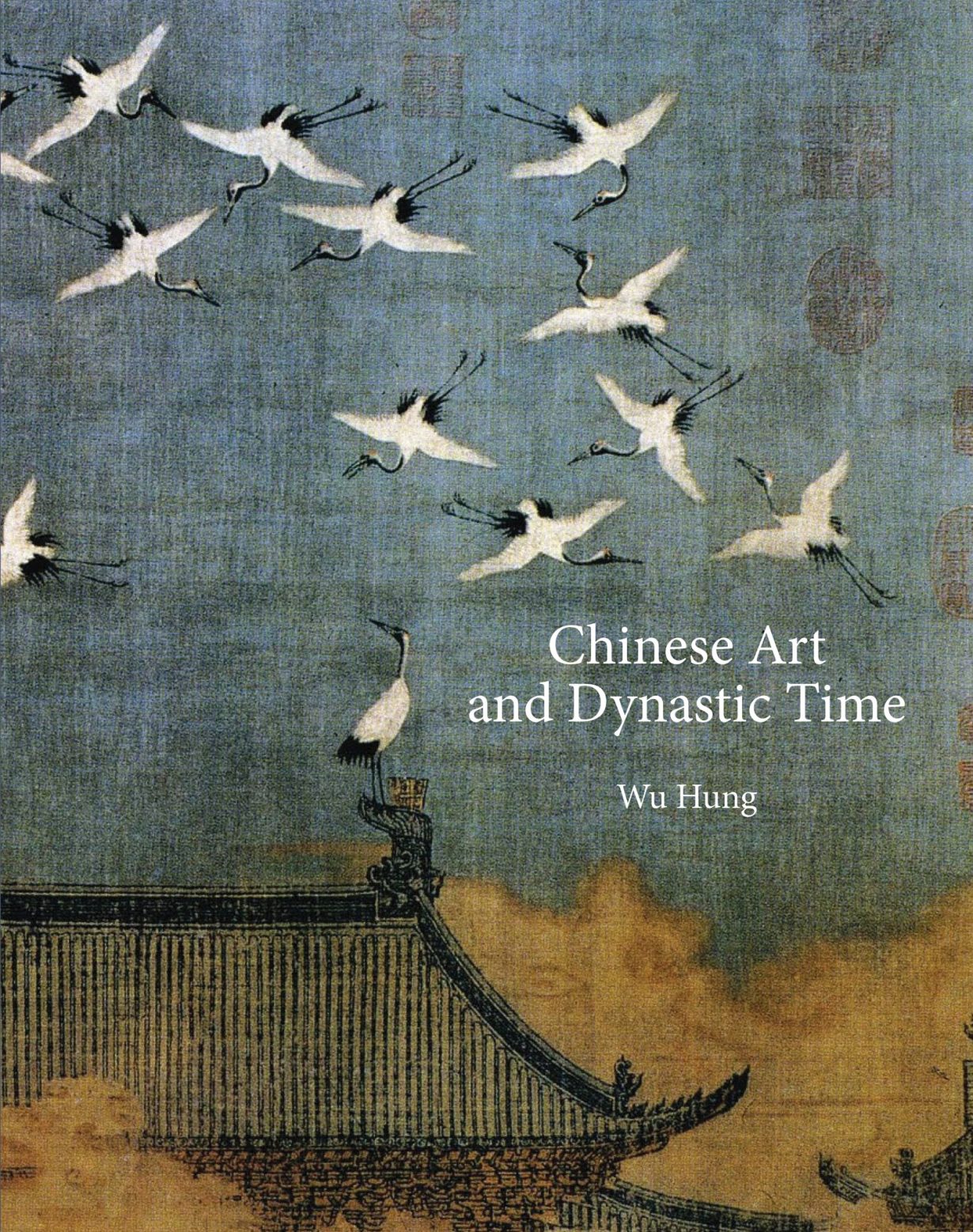

Wu Hung, Chinese Art and Dynastic Time, 2022

Princeton University Press

I’m looking forward to getting stuck into doyen of Chinese art history Wu Hung’s latest book (which began life as his 2019 A.W. Mellon Lecture series at the National Gallery of Art, Washington). Here he critically examines the use of successive dynasties as an organising narrative and conceptual tool for telling the story of Chinese artmaking over millennia. How has the notion of ‘dynastic time’ come to shape Chinese art, and our view of it? And what happens if we challenge this deep-rooted periodisation of Chinese art history? En Liang Khong

Martine Syms: Neural Swamp

Philadelphia Museum of Art, 14 May – 30 October

Power and identity, or maybe how power shapes identity, buzzes around Martine Syms’s razor-sharp interrogations of how selfhood survives the encroachments of digital culture. Neural Swamp, a new commission here in its first US presentation, unravels the experience of being Black and being a woman, in a multi-channel video installation whose three protagonists – former pro-golfer Athena, her assistant Dee and narrator Jenny – act from a script generated in real-time by AI. Dwelling on how mediating technologies that promised connectivity and togetherness have in fact driven estrangement and dysfunctional relationships, Neural Swamp wonders how far technology will reinforce the divisions and inequalities that already define contemporary life. J.J. Charlesworth

Cecilia Lisa Eliceche & Leandro Nerefuh, Panamérica, I Work and I give faith! Act 1 – Haiti or Ayiti

Boavista Gallery, Galerias Municipais, Lisbon, 21 May – 19 September

The French colonial settlers of Haiti were happy to allow the African people they had enslaved to conduct vodou rites. It was, the thinking went, a harmless way of creating manageable homogeneity amongst the many ethnicities they had captured, sold and forced into labour. After sunset on 14 August 1791 a large group of enslaved people had gathered for one such ceremony: legend has it that a spectral woman appeared, encouraging those present to rise up against oppression. The people got organised. Bwa Kayiman, the site of this meeting, became not just synonymous with the Haitian Revolution, the first successful revolt against the trade, but also proved inspiration for enslaved groups across the Black Atlantic to fight against tyranny for hundreds of years thereafter. The event is also the inspiration for an ongoing collaboration between Argentine choreographer Cecilia Lisa Eliceche and Brazilian art historian Leandro Nerefuh. Here they present the latest iteration of the project in the form of an installation and series of performances that examine not just the politics of anti-colonial resistance, but its spiritual underpinnings too. Oliver Basciano

Beyond Words: French Literature Festival

Institut Français, London, 16–22 May

For a little post-Brexit ointment, check out the Institut Français’s French Literature Festival. The week-long event features established and emerging authors from the literary scene paired with UK-based counterparts, including novelist Hervé Le Tellier, whose latest Goncourt-winning novel The Anomaly (2020) merges speculative fiction with a touch of Oulipo experimentation, discussing fact and fiction with science writer Brian Clegg; Algerian writer Kamel Daoud and Booker Prize-winning Ben Okri considering the legacy of Albert Camus’s The Outsider (1942) on the 60th anniversary of Algerian independence; novelists Marie Darrieussecq and Deborah Levy discuss weaving life and the world around them into fiction; and a talk by Fatima Daas, whose first novel, The Last one (2020), was published in translation with HopeRoad earlier this year. Reflecting the ever growing crossover from literature to cinema, there will be screenings of critically acclaimed films based on literary classics such as the 2022 Golden Lion-winner Happening (2022), inspired by Annie Ernaux’s semiautobiographical novel L’Événement (2000) – a gripping and intimate tale on woman’s right to choose, at a time when such rights are increasingly under threat – and Lost Illusions (2021), an adaptation of Balzac’s serial novel (1837-1843) about a young poet’s journey through the corrupt worlds of art and journalism. Plus ça change… Louise Darblay

Nick Cave and Warren Ellis: This Much I Know To Be True

Cinemas from 11 May

Millennial reflections on technological disempowerment and the fragile self stand in stark contrast to the more tragic, existential perspective of Gen-X rocker, Nick Cave. “In time we find out we are not in control. We never were. We never will be”, intones the prophet Nick, in the trailer to this documentary view of his and longtime collaborator Warren Ellis’s work on the songs of their two most recent albums, the mournful and elegiac Ghosteen (2019), and the apocalyptic Carnage (2021); suffering and catastrophe may be all around, but, as the increasingly spiritually inclined Cave suggests, there’s still a self, or a soul, to hold on to in the midst of it. J.J. Charlesworth

Abbas Akhavan: study for a garden

Mount Stuart, Bute, until 2 October

Abbas Akhavan’s show at London’s Chisenhale Gallery was a deeply evocative dive into materiality and trickery, folding in ancient and modern time in its earthy recreation of the ruins of ancient Palmyra, perched on top of a curving ‘green screen’ (I wrote about it here). For his first exhibition in Scotland, the artist continues his interest in probing artifice and reality – through the visual histories of the architectural folly – by placing a series of works around the gardens and within the sandstone crypt of Mount Stuart on the island of Bute. The pieces also include an audio work experienced across the neo-gothic mansion’s grounds that ‘oscillates between the wonder and revelation of sight and the classification of birds’ and a film situated in a glass pavilion. En Liang Khong

Secret Snacks

Haymarket and Chinatown (with 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art), Sydney, 9 May – 31 October

As a perennial niffler of snacks, I love a tasty recommendation. What I do not love is when someone tells you about a delicious packet of e-number laden crackers or chips or biscuits, only to reveal that these are nowhere to be found within a one-mile radius. Beyond my bi-monthly trek to the giant Chinese supermarket on the outskirts of London (where you can buy produce wholescale if you wish, and to which my cupboard dedicated to Nissin Demae Ramen – sesame flavour – can attest), sometimes I just want to know where to get a packet of Oishi prawn crackers or spring onion-seasoned Pop-Pan around the corner from, say, the office. There must be other likeminded people out there because Australia-based ‘More of Something Good’ (MSG, geddit?), an initiative founded in 2020 by graphic designers Studio Mimu to help encourage snack-seekers to venture out and support Asian businesses, offers up a directory of Asian foodstuffs that can be found at cafes, restaurants and supermarkets around Sydney, Melbourne, Perth and Brisbane. Each recommendation is given by an artist local to the area, combining personal anecdotes about their favourite snack with an illustration and its location plotted on Google maps. In 2021, MSG partnered with Sydney’s 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art for a Lunar New Year-special called Secret Snacks; focusing on 4A’s neighbourhood of Haymarket (where the city’s Chinatown is located), that edition of Secret Snacks was a fairly modest one – with just four contributors over the span of a month. This year, however, 4A is reviving the format and promising an extended run of six months during which time it will invite artists who are presenting work at forthcoming exhibitions to participate. If you’re in the area and feeling peckish, you’ll know where to go. Now, where’s my nearest pork floss bun? Fi Churchman