If we could see art and institutional spaces through the eyes of children, what would we discover?

I’m at the Barbican Cinema watching a short film by Harun Farocki, but the mood today is a little different. You might put it down to the clientele. One audience member is rhythmically hitting the seat behind me, tap tap tap tap. Another, having fed hungrily through the section of 16mm animated shorts, has lolled their head back in a drunken stupor. Yet another has left their seat entirely and is mimicking the movement of bridges in Farocki’s Bedtime Stories (Bridges) (1977) like some kind of demented ballet. This is not the sort of behaviour I’ve come to expect from an experimental film crowd, but then this is no ordinary screening.

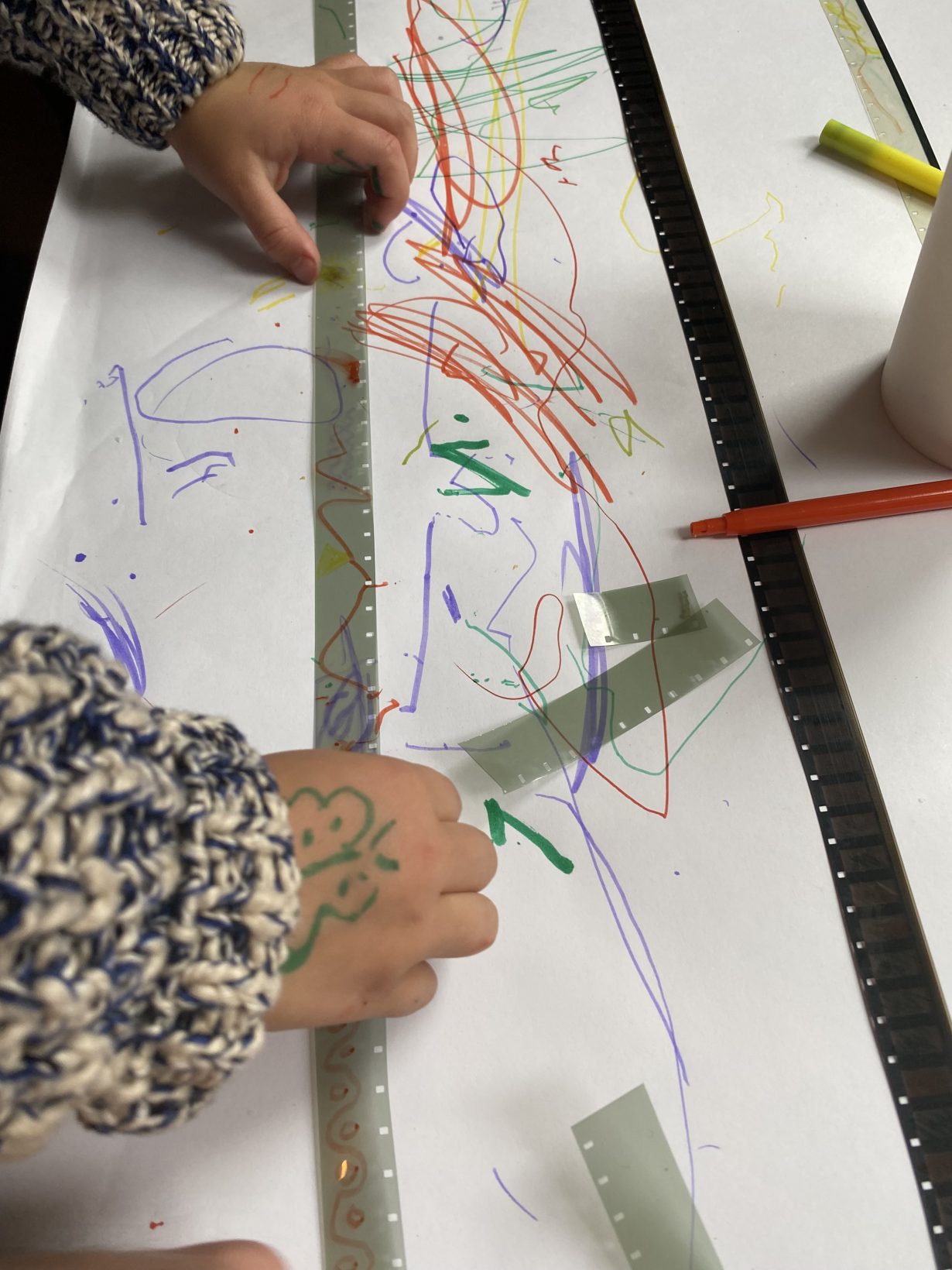

Curated by Hyun Jin Cho and Oliver Wright for this year’s Open City Documentary Festival (in collaboration with the Barbican’s regular Family Film Club strand), this one-off programme, titled Listen with your eyes, is bringing avant-garde film to Generation CoComelon, with audience ages seemingly ranging from newborns to eight-year-olds, along with their bemused carers. The screening kicks off with Thom Andersen’s mesmerising short Melting (1965), a structural film about an ice-cream sundae, and cycles through animated work by artists such as Norman McLaren and Stephanie Maxwell, as well as diary films including Lin Chuang’s tender home-movie montage, My Newborn Baby (1967). Barbican curators hand out rattles during the silent films so the children can make their own soundtracks, and a scramble for maracas quickly breaks out by the entrance. The event soon descends into chaos, with much of the audience bopping in the aisle to Margaret Tait’s hand-painted animation, Calypso (1955). Dancing and loud singing punctures the aura of quiet reverence that typically pervades artist film screenings, injecting some welcome anarchy. We end with a 16mm projection of animations made by the attending children in a pre-screening workshop using felt-tip pens on film stock. As I try to demonstrate the wonders of analogue film to my sweet-addled toddler, she makes a sudden lurch for the stage.

A strange process of defamiliarisation takes place when watching experimental films with young children. I found myself parsing the films (some familiar, others not) through the embodied reactions of a new and decidedly more interactive crowd. This seems appropriate for a mode of art practice often interested in how we perceive and make sense of images. I look for clues as to what they might find delightful or dull. Bright colours and dissolving shapes appeal to an eight-month-old, but bore the toddler, who comes to life in front of the magic trick in Ana Vaz’s hypnotic 2018 short, Amazing Fantasy.

In his now-classic 1985 essay ‘The Cinema of Attraction[s]’, film scholar Tom Gunning coined the phrase ‘the cinema of attractions’ to describe a mode of experiencing film outside of the dominant framework of narrative storytelling, favouring spectacle over story to ‘solicit the attention of the spectator’. This emphasis on display, Gunning argued, dominated cinema before 1906–07, when narrative started taking the upper hand, but reemerged in the filmic avant-garde and in other areas like the dance sequences of Hollywood musicals.

Soliciting the attention of small children is also the raison d’être of kids’ TV shows but garnered to different ends. A viral TikTok recently attempted to prove the intentionally addictive properties of the rapid-fire editing in shows like My Little Pony and CoComelon. Whereas these circulate within an attention economy that keeps children intentionally glued to their screens, experimental film can offer something a little different: a chance to actively participate in a different kind of viewing experience, engaging with films that make diverse demands on their audience. Experimental film’s fundamental accessibility has not always been understood in the popular discourse, with much of it mistakenly perceived as being difficult or overtly conceptual. Indeed, a great deal of this work actually makes a great fit for the curious minds of young children, with its tendency towards spectacle, wonder, visual tricks and gimmicks, and a preference for the short format. But it also offers an opportunity to parents and carers, who for a number of reasons are largely excluded from the hushed, self-selecting and rarefied world of artist film screenings.

Although the artworld may trade in the language of care and community, and film-industry nodes pontificate on widening access, the needs of working parents in the creative industries have been long overlooked – and art biennials and film festivals are a particular sore point. For example, it’s taken until 2019 for a major film festival to establish onsite childcare, and that is only thanks to a grassroots initiative set up by several women film programmers called The Red Balloon Alliance. Named after Albert Lamorisse’s prizewinning children’s film The Red Balloon (1956), it held its first festival daycare facilities at Cannes Film Festival that year, spawning further initiatives at major festivals in Berlin, Toronto and San Sebastián. But as Tiffany Pritchard observes in her report for Filmmaker Magazine, these have tended to be one-off initiatives, with festivals proffering the usual excuse of budget limitations. Some, like the London Film Festival, have never offered this vital resource. I can’t claim it’s related but perhaps it’s wearily familiar: after all, British culture has a long-standing tradition of hiding children from public and social life; just take the popularity of boarding schools among the upper classes. Unlike in most European cities, you’re unlikely to see any children at private views or live art events in the UK, although I still look out for them like some kind of rare bird species. This seems particularly galling in a country with the third-most-expensive childcare in the world. But if major film festivals can fund lavish, nightly drinks receptions at West End cocktail bars, they can probably afford to hire a couple of nannies and a plastic ball pit. While not necessarily a conscious decision to exclude art-worker parents, it speaks volumes about where their priorities lie.

When it comes to small, independent film festivals, where funding really is limited, this lacuna is more understandable but no less frustrating. Film festivals are critical working environments for those in the industry, and parents are having to make difficult choices, including forgoing attendance, when they could easily be accessing subsidised onsite childcare or attending accessible industry screenings. On the other hand, relaxed art events – commonly defined as those tailored for a neurodiverse, or nonnormative, audience – do not cost the earth and allow primary carers to bring children into their world, rather than parcelling them off elsewhere. While there was nothing relaxed about our trip to the Barbican, it felt special to have my family be part of a festival in which I was working as a freelance programmer, as well as offering my toddler a wider range of the cultural vegetables than the latest Netflix animated blockbuster.

As Hettie Judah notes in her polemic How Not to Exclude Artist Mothers (and other parents) (2022), a structural nexus of issues contributes to excluding art-worker parents, who are often but not exclusively mothers, from getting on with their jobs. Private views and one-off events, the latter typical of artist film screenings where film prints are often shipped over for a single night, are scheduled during bedtime. Miss it and you really do miss out. Artist residencies often exclude children from attending with their parents, and both major and independent art galleries still lack creches or feeding stations. Some of these issues are unavoidable (we’re not exactly going to start timing screenings to fit in with baby Tarquin’s bedtime schedule), but a lot of it can be easily rectified.

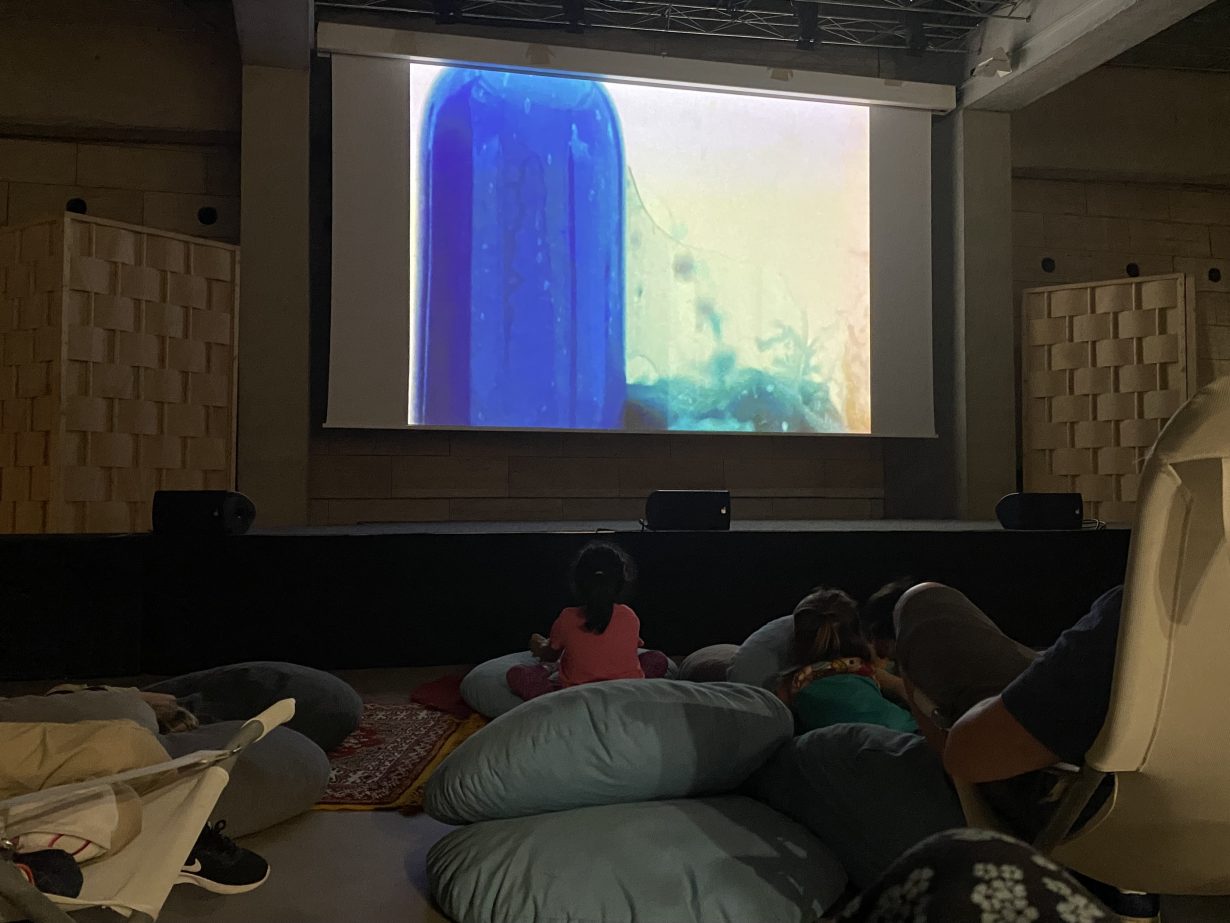

If you want to make artist film screenings accessible to parents, why not programme some work that everyone can watch? Events like Listen with your eyes are not new but still an anomaly in the UK artworld. During the 1950s, Amos and Marcia Vogel’s legendary Cinema 16 film society hosted a Children’s Cinema to show experimental work to young children that was not originally intended for them, something New York’s Light Industry recently revived. Stefanie Schlüter’s Living Archive for Children, with Children curatorial project has explored how to bring the extensive film collection housed in Berlin’s Arsenal to small children through travelling film programmes, including one held at Oberhausen Film Festival in 2012. The Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona regularly runs a free thematic film strand called 3/99, showing experimental film, including specially commissioned work by local artists, to anyone who falls between these ages. Lying on bean bags and deck chairs in the spacious basement of the CCCB, we collectively explore the presence of colour in the urban environment through vivid short films by Abbas Kiarostami, Amy Halpern, Avo Paistik and Isabelle Cornaro, among others. I was impressed by the respect with which the CCCB programmer treated her young audience. Having introduced the screening with the notion that not all films have overt narratives, she called the children onstage afterwards to chat about what they’d seen. The mics were off, and they sat together on the floor, and they talked. I wonder what they made of it all.

Sophia Satchell-Baeza is a film scholar, arts critic and programmer