From 2015: How a folding of time into gesture and process combine in paintings that wrestle with the disjunction between reality and representation

Painting stops time more radically than photography because it conveys relatively little sense of the temporal setting of its depiction. If we exempt its functional place in a depicted narrative, in which an event or act implies what follows it, the instant that a figurative painting represents does not transparently entail the time before or after, as a photograph does, because it is not causally connected to it. As if to compensate for this isolation, it defaults to the before and after of the accumulative time of the process that produced it, which is phenomenological, not illusionistic, and further obscures the depicted instant’s place in a temporal continuum. The gestural wing of us Abstract Expressionism – Pollock, Kline, de Kooning, etc – ramped up the dynamism of process’s trace to substitute for its foregoing of the illusion of depicted time. We can imagine the slash of a de Kooning brushstroke having continued on its course instead of stopping where it did, as we can imagine the legs of a horse in an Eadweard Muybridge photograph extending the trajectory of their trot.

Frank Auerbach reconciles the modernist disassociation of depiction and process by combining the enhanced process time of Abstract Expressionist gestural process with the depicted time of figuration. The two freezes – of image and process – are symbiotic. The momentum of gestural process resists depiction’s freeze, as though gesture could proceed where image stops. Process signifies a desire for continuance (every image calls a halt to what it depicts) as much as it embodies the vitality of the subject – as in both the artist (the ‘I’ of the painting) and what his painting represents. Unpredictably, given that few painters avow their work’s artifice so pointedly, the dynamism of Auerbach’s process hones our sense of the instant it depicts instead of obscuring it under traditional figuration’s protracted accretion.

And yet accretion was probably the defining characteristic of Auerbach’s early work, with its layers of black, white, red oxide and earth-coloured oils gathering, by the time a painting had reached completion, into a wrinkled and pitted crust. Material density generates an internal glow that seems to assume the qualities of either the artificial light under which Auerbach worked by night in the residential spaces in which many of the paintings were made, or the cool, wintry northern light that comes through the high windows of his studio. The gravity of these paintings is contingent upon the conversion of stodgy facture into light and formal structure. Grudgingly but decisively, paint is made to picture, its brute substance to convey a monumental stillness, but not stasis. Texture imparts the illusion of potentiality to a deposit we associate with the subject’s immovable weight. Depiction defies objecthood. The later four works in a series of six paintings entitled Head of E.O.W. i–vi (1960–1) are painted in black and-white, with the black used for eye sockets, the shadow of a nose and the receding curve of a neck forming excavations in the grizzled brilliance of the paint’s grey-white skin. Like reliefs, the surfaces literally reflect the curvatures, protrusions and depressions of the sitter’s head and shoulders.

© the artist. Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art, London

Around the middle of the 1960s, however, the paint thins and speeds up, as Auerbach begins to scrape off his failed attempts at completing a painting, instead of leaving them to progressively thicken its surface. The movement that is implicit in earlier work is channelled into the explicitness of gesture. Process takes on a performative dimension, as marks implying the drag of wet paint on a loaded brush begin to assert themselves over gesturally undifferentiated paint mass. Taking over the temporal reins from depiction, gestural process implies the limits of a merely pictorial representation of a subjectively perceived reality, as if the hand’s motion were pushing to liberate the image’s freeze. A series of paintings produced over decades and sharing a subject – a member of Auerbach’s family, a close friend, the view from outside his studio or across London’s Primrose Hill – communicate a diaristic impression, like a sequence of windows onto a world they comprehend as having aged between one portrayal and the next.

Reconciling modernist abstraction and empirical representation, Auerbach shifted the parameters of his immediate context. Among a group of London-based figurative painters, including Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Leon Kossoff and Michael Andrews, which emerged between the 1940s and 50s, he gained international recognition during the late 1970s and early 80s when painting returned to mainstream visibility, having been marginalised by a decade in which Minimalism and early Conceptualism had rejected traditional art media. Affiliated socially as well as artistically, these painters regularly appear in each other’s portraits. Their art shares a commitment to the empirical representation of subject matter that might be defined, to borrow a term of Jacques Derrida’s, as the ‘transcendental signified’; transcendental because it is a cue for representation that comprehends its referent as lying beyond the parameters of the language that represents it, a condition of which Derrida, for one, is sceptical. They reached maturity during the 1960s. To offset their work against linguistic deconstruction, the dominant theoretical position of the time, may help to highlight the refractoriness of their own positions within a contemporaneous context. Their ‘transcendental’ representations defied a deconstructive definition of the artist, the work of art and its subject matter as a triad of connected signs embedded within the circuit of an artwork. According to Derrida, ‘the thing itself is a sign’. The artist’s subjectivity and his subject matter are equally contingent upon the language that embodies them. But for Auerbach and his peers, to confine the subject to the bounds of language limited it to a generalisation. They assume the centrality of primary experience over the premediated imagery of the avant-garde of the time – such as 1960s Pop – for which the subject is always already a sign. They also rejected us modernist abstraction – Bacon dismissed abstract painting as mere ‘fashion’ – although its influence is detectable in the gesturalism of their idioms, even in the work of Freud, probably the most reactionary among them.

But in Auerbach’s art, the impress of modernist abstraction, in both its gestural and geometric manifestations, is clear, although the urgency of its historical proximity is put into relative perspective by his engagement with the entire Western painting tradition looming behind it. His historical sense combines the allusive modernist’s vigorous, even hostile, transformation of the past with the emulousness of the traditionalist’s homage. We can intuit the paintings he has been looking at – and until the 1980s drawing week in and out in London’s National Gallery – through compositional configurations that find their way, as if by osmosis, out of art-historical precedence into paintings of a subject and idiom remote from their antecedents.

© the artist. Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art, London

Bacchus and Ariadne (1971) is unusual in directly representing an existing painting: Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne (1520–3). It could be its primary-coloured skeleton, a severe distillation of figural dynamics to a linear network. A more characteristically tangential relation to art history is found in The Origin of the Great Bear (1967–8), which also began with a commission to interpret Titian. Although ostensibly a landscape based on drawings of Hampstead Heath, it gestures to two Venetian sixteenth-century paintings in London’s National Gallery: Bacchus and Ariadne and Tintoretto’s The Origin of the Milky Way (c. 1575), each featuring a circle of stars in a blue sky. The title refers to the myth, related in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, of Callisto’s transformation into a bear, then a constellation. The Titian-themed commission, the stellar conceit and the link to the Metamorphoses returns us to Bacchus and Ariadne, but Auerbach’s title and composition draws Tintoretto’s painting into the equation. The dragonlike form in the top left, which could be adumbrating the dark side of a cloud mass over the Heath, follows the contours of the serpentine cloud in the top left of the Tintoretto. Auerbach has suggested that it represents the descent of Jupiter from the heavens in the Callisto myth. The compositional momentum of the Venetian paintings, from top left to bottom right against a background of brilliant blue – Titian’s motley tumble of figures down a diagonally-sloping foreground, or Jupiter’s dive towards Juno’s breast in the Tintoretto – finds its counterpart in Auerbach’s yellow monochrome ground through which a concentration of dark shapes unravel, from right to left, as gestural impasto.

The circle of stars, translated by Auerbach into stubby strokes of sky blue oil, converts the mythological licence of the Venetians into a rhetorical manifestation of the gulf between a painting and the natural phenomenon it represents, by qualifying the yellow ground as a negative representation of the ‘brilliance’ of night (in the sense that orange often predominates in Auerbach’s paintings of Mornington Crescent at night), a pictorial conceit as fabulous – in an empirical representational context – as the Venetians finding stars in a daylit sky to visualise their myths. Unlike the 1971 painting, with its more mimetic relation to the original, The Origin of the Great Bear is a melting pot of allusions and perceptions – literary, pictorial, topographical and formal; an extreme example of Auerbach’s circuitous method of discovering likeness through otherness, in this case between the idioms of twentieth-century empirical landscape representation and sixteenth-century mythological painting.

A predilection for cultivating the maximum disjunction between a painting’s forms and the perceived reality they transform draws him to accord pivotal significance, in the modernist period, to Matisse’s 1900 15 period, which dwells on a rift between representation and reality in order to return us, at least in the portraits, to the specificity of a likeness. The lines dividing the geometric shapes of Matisse’s Head, White and Rose (1914) – a painting Auerbach has spoken of as central to his concerns – form an oblique metaphor for the head of the French artist’s daughter, Marguerite. Cubism, which the painting adapts to its purposes, purveys a relatively generalised depiction. A synthetic geometry is presented as the equivalent of a unique, organic subject. But the geometric structure is also a barrier between viewer and depicted object, the pictorial equivalent of the separation between a linguistic metaphor and the reality it illuminates. In metaphor, the remove from an object, provided by the object to which it is compared, refreshes the reader’s vision of it. But the portrait-as-metaphor must double as the resemblance of a simile in order to function as a likeness of its subject.

Auerbach’s art realises this paradox; that, in his words, ‘the living activity is something that feeds into an architecturally separate form’. Matisse’s exposure of the occult alogic of painterly representation is reinvented as an idiom of record in the British empirical tradition of Holbein, Hogarth, Constable and Sickert. Among modernist art and literature’s characteristic tropes was the transference of emphasis from an artwork or text’s referents to its writer/artist, from object to voice. Auerbach places a modernist turn on the tradition he adapts by emphasising that however objective a painting’s idiom, its only causal link is to the artist’s hand, not to what it represents. A painting is anchored to its maker before its object, to its subjective cause before its objective effect. Empirical representational method is subjected to the disjunctions of an abstract Modernism it would have rejected. When I talked to him in 1986, Auerbach claimed that he wanted his paintings to be “like nothing on earth, but like” what they represent. That conundrum is realised by proposing that the artificiality of a pictorial structure is commensurate with the accuracy of its representation.

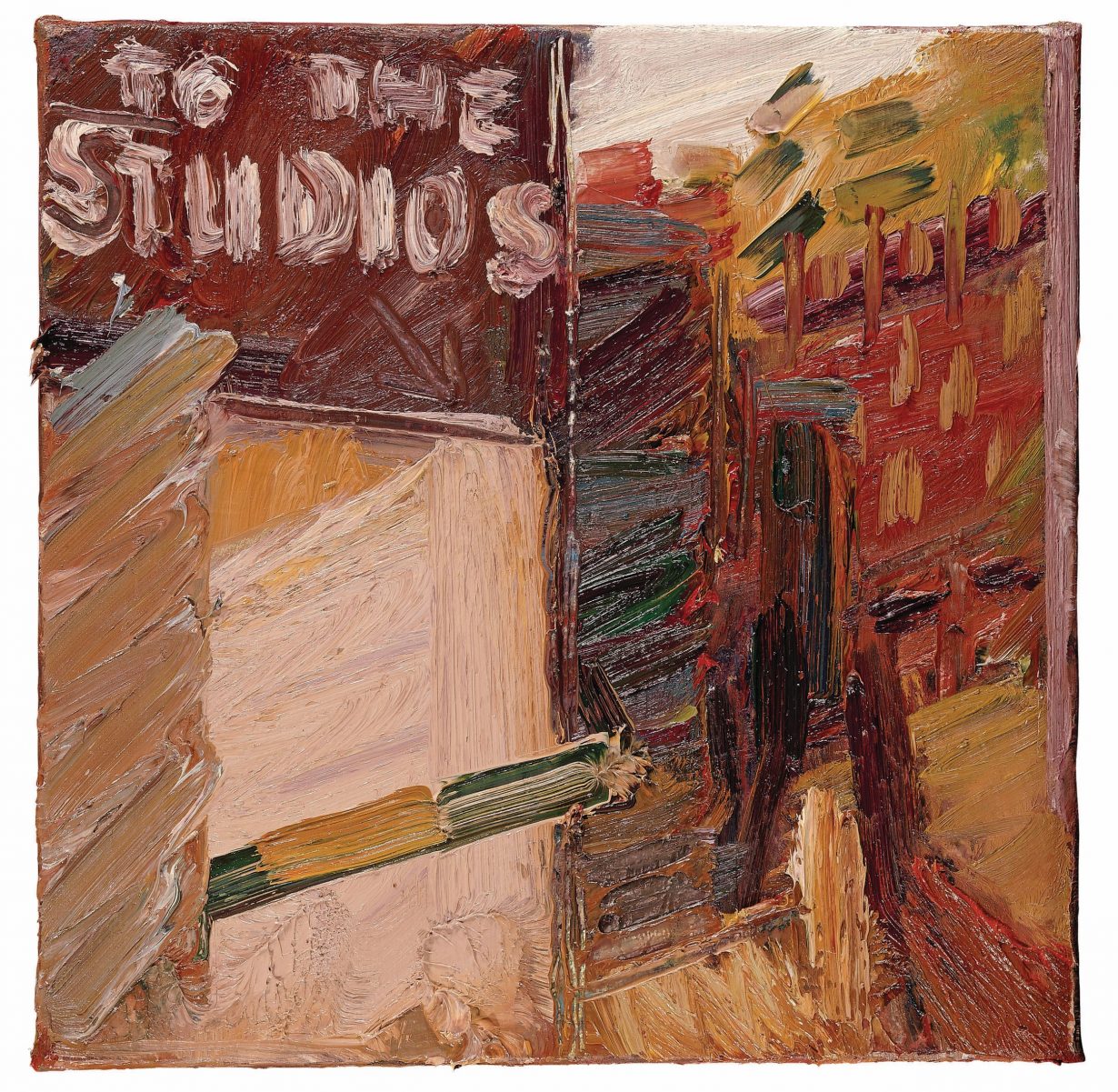

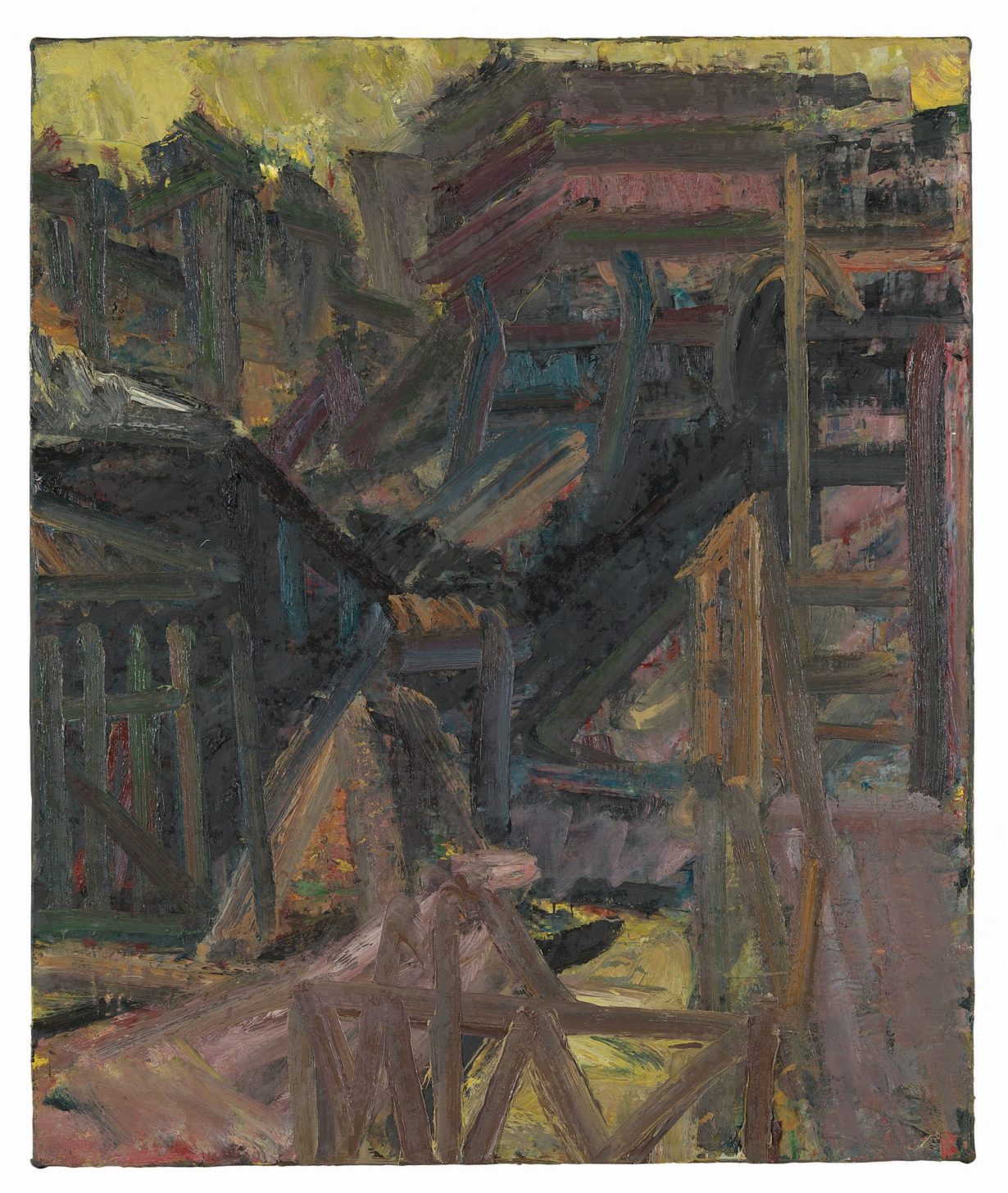

To the Studios (1979–80) raises a weave of gestural contour lines almost to the top of an upright rectangle, leaving a margin of yellowish sky so brief, the geometries of the canvas corners define it as shape before space. These geometries are the metaphorical equivalent of architecturally heterogeneous alleyways and roofs receding through a densely packed urban district. A dour spectrum of cobalt turquoises, chromium greens and greyish mauves evokes a degree of daylight and temperature – autumn/winter, early evening – through chromatic and textural invocation before imaging. Connotative colour is invested in a geometric structure that rejects, in its abstraction, the contingencies denotative representation implies. The painting issues a decoy, a synthetic abstraction that maintains that oil paint, applied with a large hog brush, must inevitably be artificially removed from the facts of the cityscape it claims to represent, therefore it may as well stress that difference. Geometric gestures subordinate depiction to process. Auerbach confirms this esoteric equation between abstraction and accuracy: ‘I do like a clear expression if I can get it – something that seems to lock like a theorem.’ A theorem is a mathematical statement that is not contingent upon empirical substantiation, and what could be more removed from his representational method and the naturalistic subject matter upon which it is focused?

The gate leading into the left side of To the Studios is a series of vertical strokes traversed by two parallel horizontals bridged by a diagonal. Bracing the rise of the cityscape, it is a cartoonish sign for a gate as much as a geometric cipher that replaces it. The composition’s pattern of interlocking gestures resembles similar geometric networks that appear throughout the series of paintings (1977–) – variously titled To the Studios, The Studios, The House and Next Door – based on the view down the alleyway leading to the studio (in Camden Town, north London) that Auerbach has occupied since the early 1950s. In the context of his oeuvre, these variations on a single composition extend a spectrum that, in sum, comprehends their shared inability to categorically depict what they all connote. They suggest that the scene that is unavailable to all of them lies somewhere between them. Compositional and chromatic discrepancies, viewed across the spectrum of the series, have the converse effect of making their common subject seem intimately familiar to us, although none of the differing versions provides us with a topographically reliable depiction. The axis of variations, revealing their mutual otherness from what they all represent, conversely measures the precision of Auerbach’s representation by implying how profoundly a composition is altered by his taking a fraction of a step to the left or right, or painting in different light conditions. Auerbach has claimed that to shift his easel an inch or two in relation to a stationary model profoundly alters a painting’s compositional variables.

The interwoven gesture and erasure that composes To the Studios has a symbolic function. Paint is scraped away with a palette knife to leave blurred traces visible through the strokes that qualify them. The blur of absence offsets gesture’s assertion of presence, a combined signifier of the subject’s remove from the pictorial structure. What we see ‘through’ the lattice of foregrounded gestures blurs into the image of absence, and by extension, pastness: a pastness that is first the literal pastness of an overpainted stratum and, second, the pastness of a superseded image. The overpainted geometries are, by definition, self-negating; abstractions inserted into a depictive space that can only assimilate them by denying its own logic.

© the artist. Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art, London

Auerbach has claimed not to be conscious of his geometrical ideograms as being of a separate pictorial order from the representations they structure, as though they constituted the struts of an armature that should be assimilated by the painting’s overall metaphor. The red and green zigzags of Primrose Hill, Summer (1968) are only ‘space dragons’ – abstractions that clash with their depictive context – if you insist on viewing the painting as conforming to a conventional landscape layout of sky and land zones divided by a skyline. But the painting’s ground heckles this reading. A yellow monochrome field, nuanced by gestural process, is etched over with lines that do not function diagrammatically, but as structural underpinnings so concise their generalisations are posited as penetrating specificities, distilled essences of collected perceptions. What we know of Auerbach’s process confirms this. A sequence of sketches is reduced to a geometric analogue that condenses the disparities of a series of separate viewings. He has described this process as traversing an axis from information gathering to the acknowledgement that ‘one can’t make an image’.

The monochrome yellow ground and geometric structure of Primrose Hill, Summer are modernist tropes superimposed onto an empirical representational template. But this apparent clash has modernist roots. Empirical objectivity, after all, was among the cornerstones of modernist method, with its imperative not to credit content that cannot be sourced from an identifiable fictional or artistic consciousness. Self-reflexively, Auerbach has a process designed to forge an objective connection to a referent default to gestures that testify primarily to his own trace, and by implication, to his subjectivity. This is a classic modernist inversion, a circling of subject matter (Primrose Hill) back to artistic subject (Frank Auerbach). Defaulting from image to gesture, the painting negatively qualifies the subjectivity of which it is a trace as solipsistic, producing what literary critic Denis Donoghue terms ‘a subjective metaphor’, ‘an attribute of the narrator’s mind and no one else’s’. Describing his process of drawing from the landscape, Auerbach transmutes his subject from objectively causal (‘projection on the retina’) to subjective terms (‘the mind’s grasp’): ‘One looks – tries to understand what one sees as solid matter in space – and then makes a pictorial image, not of the projection on the retina, but of the mind’s grasp of the material… There is no one-to-one relation of mark to object (such as lamppost, branch, puddle, etc). The painting is a single indivisible image of my grasp of their relationship.’ But the performative dynamism of this process strives to bridge the separation between subjectivity and the world by pitching pictorial geometries as universally applicable metaphors.

Auerbach’s attempt to universalise a subjective language may be essentially modernistic, but it is also characteristic of a strain of British empirical painting, distinguishing, for example, Constable’s commitment to the prompt of primary experience from Turner’s relative conformity to the natural spectacle of a Romanticism already pictorial in essence. Constable’s insistence on the circuitousness of the link between a painting’s language and what it mediates challenged the presumptions on which late- eighteenth-century landscape painting – which was his departure point – was based. Romantic sublime painting proposes an equivalence between natural and pictorial splendour. But the dark foreground of the lower third of Constable’s full-scale oil sketch for The Leaping Horse (1824–5) is a protomodernist exercise in translating palette-knifed gestural process, leavened by earth-coloured glazes, into a texture that conveys the sensory experience, more than the image, of soaked sedge and rotting timber glittering under a slick of dew. Process (glazing) is a sign more than facilitator of representation (dew). But in the 1825 exhibition version of the painting, these passages have been brought to order, made to bear a more conventional depictive weight. The formal occasion coerced a retreat from the full force of Constable’s initial perceptions.

© the artist. Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art, London

To emphasise the arbitrariness of the link between a painting and its subject is an index of subjectivity’s powerlessness to access the world. Juggling empirically objective and solipsistically subjective modes – with the former cast as a bridge across the divide between the painter and what he depicts – Auerbach produces a record of consciousness isolated by the schism between the subjectivity a painting embodies and the referent it can only denote by admitting that it lies outside its structure. The schism implies an existentialist heritage. Auerbach emerged during the early 1950s, as Sartrean existentialism – with its exploration, in a novel such as La Nausée (1938), of the heroic and absurd isolation of subjectivity from the world in which it finds itself – was in the ascendant. The extravagant buildup of materials that characterises the paintings of the 1950s and early 60s overloads the process end of the balance between process and image.

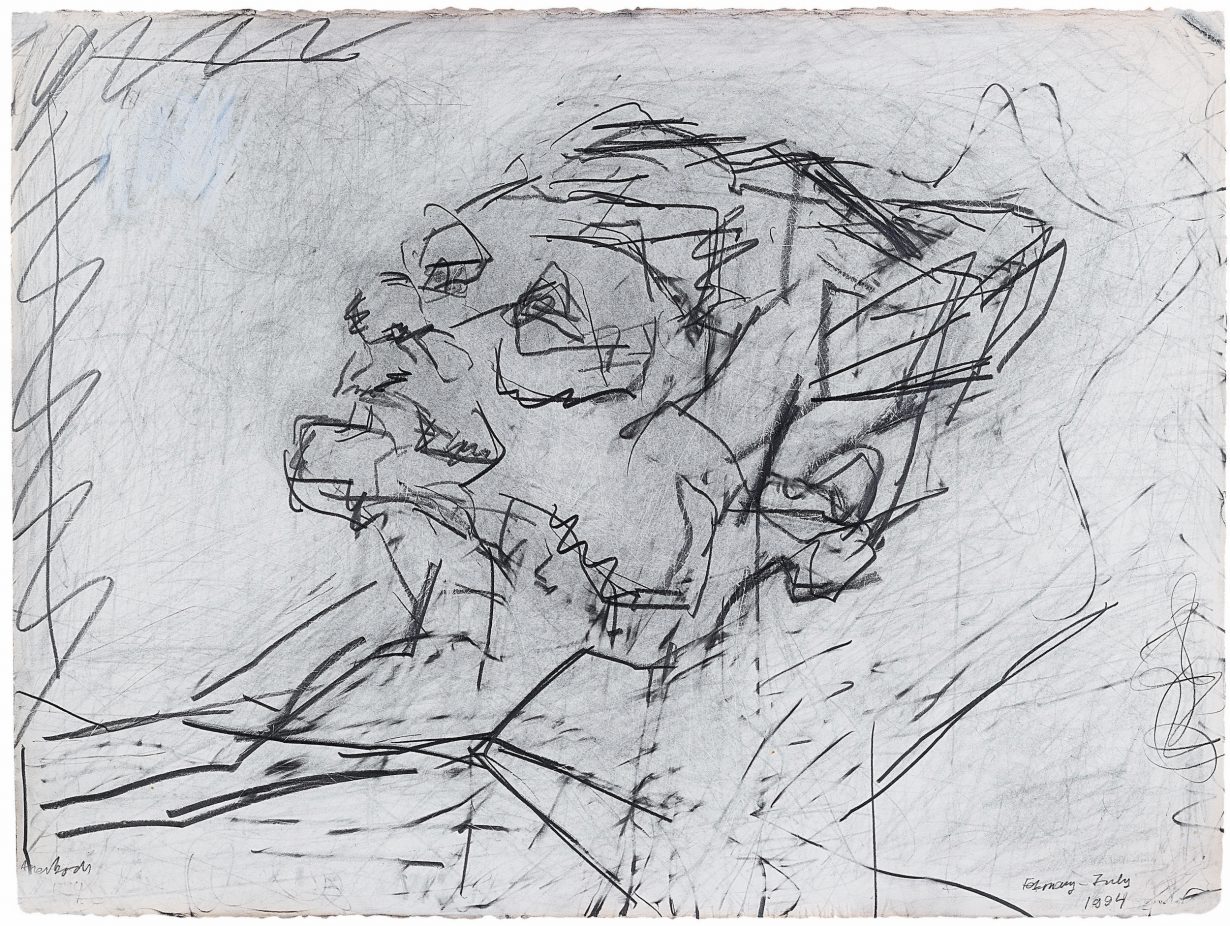

Process appears to be consuming the picture it articulates. The axis of representation – from artist to painting to subject – doubles as that between alienation from and connection to the external world towards which an individual consciousness reaches. Oil paint gathers into a relief that testifies to the breakdown, if not failure, of two-dimensional pictoriality. The swellings of ochre and earth-coloured oils that dominate Auerbach’s early portraits of Estella Olive West manifest an artistic distance between painting and subject as synonymous with the contingent one between a young man and his lover. But Auerbach proceeded, during the course of the 1960s, to attempt to objectify his methods, converting a materialistic process into a conceptual structure that not only embodies but connotes and emblematises its relation to the reality it invokes. In his portrait drawings, the distance between language and sitter is realised as a geometric aura surrounding a subject it can only surmise. The drawings are platonic in comparison to the paintings’ sensuous embodiments. Reclining Head of Julia (1994) encloses its subject’s bone structure in a web of fraught scribbles that would be caressing if they were not contingent upon the slight delay between a gesture and what it connotes. The web of marks is a snare that never quite touches its quarry. Auerbach has described drawing as ‘an immensely satisfying intellectual activity’, contrasting it with a painting process subject to the intractable contingencies of paint’s viscous entanglements.

© the artist. Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art, London

His portrait paintings are more ambivalent about the remove between gestural language and connoted subject. Material fluidity is an embodiment as much as a metaphor. The ochre mass of the head of Reclining Head of J.Y. M. (1975) manifests an equation between paint and human flesh that recalls Auerbach’s materially denser early portraits. The mauves surrounding the ochre’s deposit have been scraped back, thinning surround to background, as though the paint’s thickness were analogous to the physical proximity of what it represents. But the black line that zigzags between brow, temple, ear, cheek and jawline is a geometric superimposition, and the eye is as impossible to distinguish from the shadow of its socket as hair from flesh. Withdrawing into metaphorical abstraction, the portrait ghosts the individual it portrays. Its structural specificity can only recall the specificity of the person it cannot grasp. This testimony to the subject’s elusiveness makes the painting a statement not of possession but absence, of the subject’s presence beyond the language that pictures it, and therefore of an unmediated and unmediatable reality.

Seen in this light, the painting is a much more equivocal reversal of a Derridean deconstruction of representation than it first seems. For Derrida, ‘transcendent’ representation is a repression of language because it qualifies it as a mere accessory after the referent’s fact. As if conforming to this perception, Reclining Head of J.Y. M. avows its limitation to painting’s language, but only equivocally. Its illusion of physical volume represents a striving for the reification of a pictorial embodiment, but one that always comes up against the Derridean limitation of the signified to the sign. That limitation is here made synonymous with a Matissean gulf between language and reality. It is in that synonymity, by which abstractions connote a reality they can only elide, that Auerbach tasks a language that is eminently deconstructive with invoking the transcendental ‘presence’ that Derrida foreswore. But he charges that invocation of a presence beyond pictorial language to operate as a sign that something is not here that was. This is not the absence of a conventionally depictive record, such as a photograph, which pictures as present what its freeze implies is past. Reclining Head of J.Y. M. testifies to its subject’s absence even in its own depiction, and by extension in that of any painting, through a metaphor based, as Donoghue says, on ‘an occult likeness between things essentially unlike’. Depictive supersession is equivalent to morphological otherness. But the physical resistance of gestural process, with its illusion of presentness, to this double remove from the subject is itself impeded by the freeze that makes it a trace of gestures enacted in the past.

This give-and-take between the pastness of depiction, the presentness of process and the pastness of its traces makes Auerbach’s paintings difficult to photographically reproduce, an implicit critique of photographic representation. Photography transplants process into an illusionistic space that suppresses painting’s qualification of depicted time. Material presence becomes an image of presence, super-imposing a conventional axis between a representation and its referent onto paintings that question their access to their subject. Glenn Brown has attempted to recreate this photographic distortion in the series of paintings he has produced of reproductions of Auerbach’s portraits of ‘J.Y.M.’ (Juliet Yardley Mills). He casts gestural process as a grotesque figment suspended in photographic space, a tangle of gestural flourishes that have been assimilated by the depiction they were meant to hold at arm’s length. But Brown illuminates the originals negatively, by severing the empirically objective link between an Auerbach and its subject; its last-minute demand that a metaphor based on the unlikeness between itself and its object should assert their mutual resemblance. We recognise that the putative empirical representational link to J.Y. M. is lost to Brown’s depictively present images of Auerbach’s absenting abstractions. In contrast, by eliding, through metaphor, the subject his paintings are set on recording, Auerbach implies that their pathos lies not in claiming to return us to the past but in convincing us that it is gone.

This article was first published in ArtReview October 2015