“So much of the institutional language about caring concerns the physical maintenance of objects. But when there’s some other intangible function, there is no space for this to be considered.”

The best artists often have doubts about whether their work has succeeded. That worry is not usually as existential as Gala Porras-Kim’s concern, though. We’re in South London looking at a large paper marbling work, a swirling landscape of yellow, orange and green ink. “I don’t actually know how to contact the afterlife,” Porras-Kim tells me. This is her earnest attempt, however, using ‘encromancy’, an early form of ink divination, to communicate with the spirits of citizens of first-century BCE Shinchang-dong, an area of present-day Gwangju, whose bodies have ended up in the city’s National Museum. That the resulting abstract print has a geographical feel is a good sign of its success, I offer: Porras-Kim had asked the dead where they would ideally have their remains kept, given that they had been removed from their original burial places and have, for centuries, been in storage and, more recently, on display in Gwangju’s institutions. Typically for her work, the Colombian-born, Los Angeles-based artist is displaying alongside her marbling work a copy of a letter she sent to the museum regarding the skeletons in their collection. ‘We, as living people, will have to negotiate between our desires to think of them as historical objects, and the respect for the individual person and their desires for their afterlife,’ the artist writes. Of her divined map, she says, ‘The actual place remains illegible to us, and might not even exist on our planet.’

The work, titled A terminal escape from the place that binds us (2021), is part of Porras-Kim’s ongoing interest in the dual function or status of objects as they pass through history and are institutionalised by museums. When actual human bodies enter such collections, those questions of status and transformation are heightened. “In different countries, they have different laws over human remains,” she explains. “When does a cadaver become old enough to become an object? At that point can it be removed from wherever it’s been left? Can it be owned? How do you decide? I’m interested in contract and regulation, and how specific regulations provide the framework through which we view an object.” A work presented at the 2021 Bienal de São Paulo features a handprint made in ash on a tissue. Here the letter, addressed to Alexander Kellner, the director of the Museu Nacional in Rio de Janeiro, queried the idea of trying to restore the remains of ‘Luiza’, the oldest human fossil in Latin America, an object/person mostly destroyed in the fire that gutted the institution in 2018. The letter’s subject line (and title of the work) pithily notes: ‘Leaving the institution through cremation is easier than as a result of a deaccession policy’.

Porras-Kim and I are talking ahead of a new exhibition at Gasworks, at which both of these recent biennial projects are being shown, alongside new works. Naturally, as an artist who explores the legal and moral status of museum objects and offers a critique, and indeed some possible answers, to current debates around national collections, institutional care, restitution and decolonisation, her attention in London has turned to the British Museum. As Gala- Porras points out, it is, for better or worse, “the boss of collections”.

“My overall project is how specific a subcategory of objects, whose original function might still be ongoing, are living and stored in different types of institutions,” she says. If we think about what the purpose of a museum object is – its current function – it would be as a tool to help us understand a particular historical period, or to demonstrate how a specific society lived or continues to live. Yet most of the objects in institutions such as the British Museum were not created with that aim; they were conceived instead for either a very practical purpose (all those urns, weapons, clothes) or a spiritual one (statues for veneration, religious icons and offerings). “Those functions did not have an end date built into it, so what happens when that object gets accessioned into a collection? It’s a question of priorities. In the British Museum there’s so much Egyptian stuff, which was fascinating because the Egyptians planned really well for their afterlife. If you have a civilisation of people that had planned to live on forever, then in their theory at least they do. We need to take that into consideration. I mean, firstly we have no idea whether they are wrong or not, but also they are living on, at least in our memory. It is just a different type of living.”

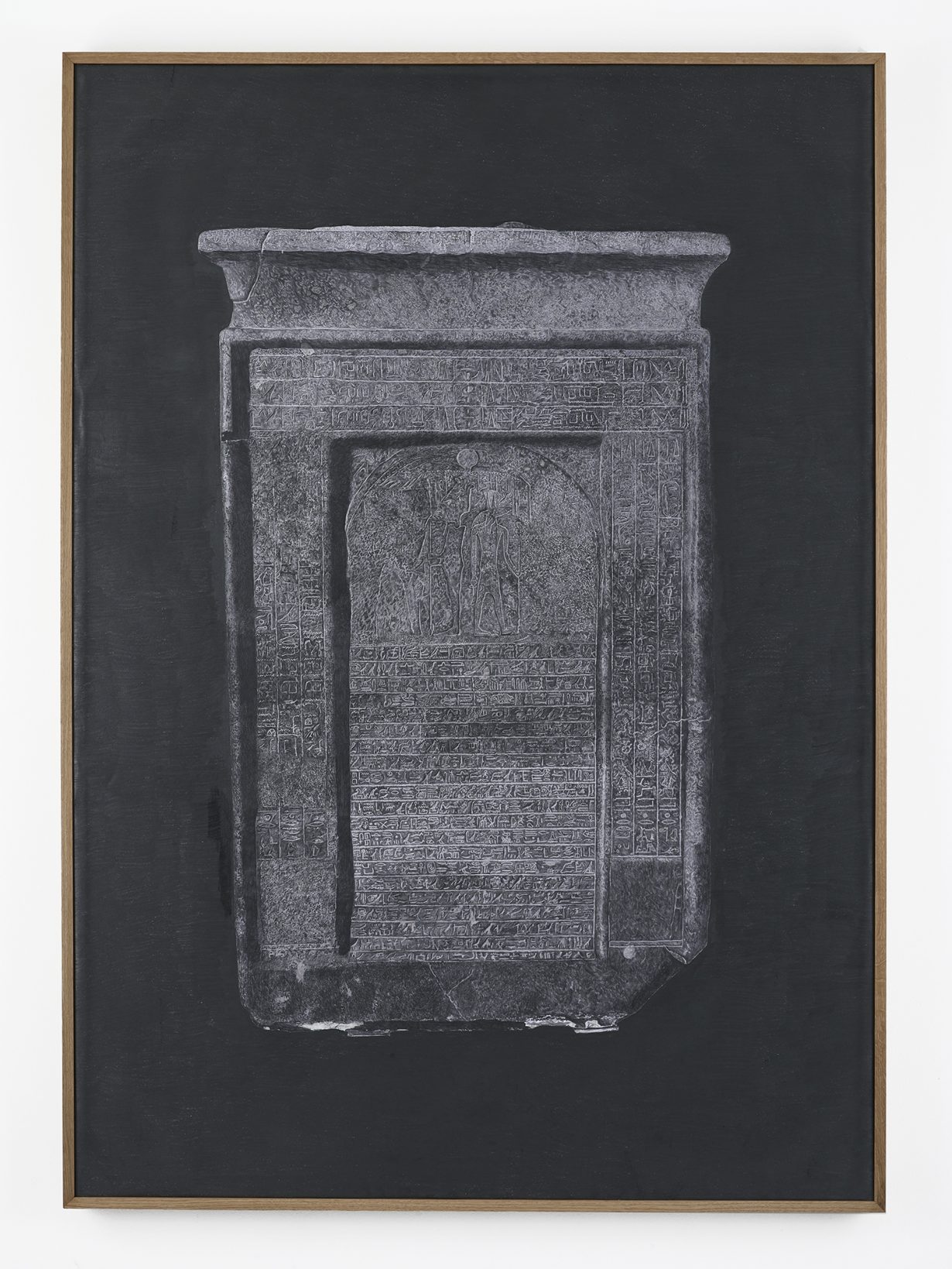

replica of sarcophagus EA71620, 106 x 228 x 89cm; and Mastaba scene, 2022

graphite on paper, 269.5 x 183.5cm. Courtesy the artist and Gasworks, London

Sunrise for 5th-Dynasty Sarcophagus from Giza at the British Museum (2022) is a scale reproduction of one such ancient Egyptian object from the museum, except Porras-Kim’s version is on a turntable that allows the tomb to be pivoted approximately 25 degrees. In Egyptian tradition the dead faced east to the rising sun when buried. “It is supposed to be facing a specific direction, and [at the British Museum] it’s not. The work is just a proposal to rotate the sarcophagus, so it’s still on view, except now it’ll be facing the right way.”

“It is a question of care,” she continues. “So much of the institutional language about caring concerns the physical maintenance of objects, like the conservation and preservation of the physical things, but when there’s some other intangible function that might have a priority over the physical object, there is no space for this to be considered. Could there be a department within the museum tasked with looking after the spiritual aspect of an item in the collection?”

Porras-Kim wrote to the British Museum’s curator of bioarchaeology, asking just such a question. ‘Since [the dead] have expressed and determined the way their material and spiritual parts were to be kept, this provokes several questions about their current existence in the museum – out of their final resting places – and a closer look at their condition in the current and ongoing after- life,’ Porras-Kim writes, admitting that it ‘could seem daunting to understand so many people’s eternal plans’. Yet a gesture such as the artist suggests – merely shifting the angle of one exhibit – seems to offer a wider recognition of an individual’s rights or a lost civilisation’s historic agency, however long ago they may have passed into history.

Sometimes, though, the impetus to care for the original spiritual or ritualistic function of an object risks undermining its physical care. Harvard University’s Peabody Museum has a collection of around 30,000 objects that were removed by the American archaeologist and diplomat Edward H. Thompson from the Chichén Itzá cenote, a sacred Mayan sinkhole on the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico, in the early twentieth century. The objects were likely placed there originally as an offering to Chaac, the Mayan god of rain and thunder. The museum stores these artefacts in a temperature-controlled environment, free from all damp. “The current idea of conservation, which is meant to keep things very dry, is in opposition to what their original relationship with the rain might have been,” Porras-Kim says. “The current methodology of the institution is getting in the way of that other type of caring. It’s not one or the other, I’m not saying these things should be thrown back, but maybe we can think about how much rainwater this specific object can be exposed to before it gets damaged. I think it’s so much about gestures. We have to acknowledge that its status as a historical object is not its only function.” For Precipitation for an Arid Landscape (2021) Porras-Kim combined copal, a clear resin from the copal tree and one of the main materials found in the sacred cenote, with dust taken from the museum storage in which the Mayan objects are kept, to create a slab of material that might serve as a proxy for the exhibits. Wherever the work is shown, curators must douse it with rain collected during the exhibition’s run. It too is accompanied by a letter to the exhibiting institution. I ask her if anyone has ever replied to these missives, mostly addressed to senior members of staff. Rarely, she says, but she does talk to researchers and registrars constantly.

ink on paper and document, 186 × 267 cm. Courtesy the artist

“The registrars or just people within museums are often so excited to talk to me because they recognise that I want to talk about stuff that they too think about, but that the institution provides no space for… Lately I’ve been reading a lot about ledgers, the beginning of things. There’s an existing cataloguing structure that only allows for pre-set subcategories. If you describe an object through those labels, then spiritual life doesn’t even exist. There’s no columns on the Excel sheet for that kind of information, so it disappears once the object is accessioned. They are classified in a very scientific way. But cultural objects are forever in flux; how do we reflect this empirically?” Porras-Kim says she began to be invited to make projects within museums as part of the recent drive for institutional self- reflection. “But they don’t have to bring in an artist. Just put an anonymous comments box in the staff lunchroom and then once every couple of months have a totally free discussion.”

In 2017 the artist became interested in a collection of burial figurines and vessels from Colima, Nayarit and Jalisco on Mexico’s Pacific Coast, dating from between 200 BCE and 500 CE, held by the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art. In the museum’s catalogues, and in the display captions, they were grouped together under the name of their collector – and donor to the museum – Proctor Stafford. At LACMA itself, as part of her participation in that year’s edition of California art festival Pacific Standard Time, Porras-Kim offered, through a series of drawings, an alternative indexing method, ordering them simply by scale. Alongside these drawings she showed a series of ceramic works, made in the style of the Mexican objects. Each was fitted with a GPS device, allowing the artist to track the objects as they continue their journey out of the museum, perhaps into a private collection, and life beyond. “When an institution says it wants to learn and teach people about objects, they often just focus on one original story,” she says. “We don’t get to hear about all the other actors on its historical paths very well. What would be interesting to me is interpretation that said how much tax write-off a collector got for donating something. What have been the various functions the object has performed before it arrived in the museum? Those things are interesting.” When the project moved to a solo exhibition at Labor, a commercial gallery in Mexico City, Porras-Kim researched all the locations where these burial objects were known to have been before ending up in the museum, and produced another series of drawings showing them in the cave where they were found, and on domestic mantelpieces. I wonder about the future lives of Porras-Kim’s works, as they enter the opaque world of the contemporary-art market.

There are many who might argue that gestures don’t go far enough, that these objects must be returned to where they were taken from. The artefacts at the Peabody, for example, were smuggled out of Mexico, and in the 1920s the Mexican government tried to recover them. (Harvard University did return some items in the 1960s and 70s.) Even if many of the exhibits in the world’s museums weren’t looted as such, the history of colonisation and imperialism means that they are often symbolic of repression and power struggle. Which could also be an argument for keeping them in place.

“You can’t escape history,” Porras-Kim says. “We have to think instead about how the objects inside a collection can change the building around it. Like the mummies, for example, their presence turns the British Museum into a literal tomb. Let’s treat it as that. It’s still a museum, but that is its secondary function. Everybody is trying to decolonise the museum, but okay, then you’ll have to remove the whole thing. How do you have a decolonised museum when the building, the city, the country, itself comes from that history? History is additive, so this building could have been colonial made, but you can change it and add to that. Things can be multiple.”

Gala Porras-Kim’s solo show Precipitation for an Arid Landscape

is on view at Amant, New York, through 17 March, and Harvard Radcliffe Institute, Cambridge, MA, through 2 July; her exhibition

Out of an instance of expiration comes a perennial showing

is at Gasworks, London, until 27 March; her exhibition Correspondences towards the living object can be seen at the Contemporary Art Museum St Louis from 25 March to 24 July