A group show brings together 14 artists and collectives from across South and Southeast Asia to consider image-making and community, and image-making in community

In one corner lies a pair of green khakis. A single taut thread extends from its frayed, holey crotch and is affixed to the wall with a bit of red tape. Curated by photographer Sohrab Hura, this group show brings together 14 artists and collectives from across South and Southeast Asia to consider image-making and community, and image-making in community. One imagines a gossamer web that connects all the other works and walls here and perhaps reaches across the Indian Ocean too: even as the region is doubly ravaged by the forces of COVID-19 and state-sponsored ethnoreligious violence, these are the ties that bind.

More overtly yoking the show together are two diaristic vignettes from Hura, about dealing with his mother’s declining mental health and the first roll of film he shot. They are scrawled onto the wall alongside chatty annotations about each artist – and Hura’s relationship to them – that take the place of any more formal wall labels. There is a sense that some or all of the participating artists could be swapped out and the show would read the same. This is not a bad thing, even as there’s a danger of artists being instrumentalised in service of what is functionally a Hura solo show. Rather, it feels like a screenshot of a dynamic, transnational scene in flux, captured at a particular moment in time.

A number of works feature further annotation. Photographs from Nida Mehboob’s ongoing Shadow Lives series chronicling the quotidian persecution of Ahmadi Muslims in Pakistan are paired with handwritten Urdu texts. And taking up much real estate is a selection from The Feminist Memory Project, a visual archive (launched in April 2018) from Nepal Picture Library. Between 1960 and 1990, the former monarchy outlawed Nepal’s democratically elected parliament and seized control of the government. The archive traces the life and experiences of two revolutionary women during this time, pairing family album snapshots and printed matter with bits of oral history and red connective thread to reconstruct an alternative history of the time.

31 x 46 cm. © the artist

Courtesy Ishara Art Foundation, Dubai

Today the Communist Party is in power, but a nearby work from Bunu Dhungana suggests that the feminist struggle, at least, endures. In its eight self-portraits Dhungana addresses the many violences germane to

being first a girl, then an unmarried woman in Nepal. She variously sports red significations of marriedness – a bindi, a sindoor, a ghumto

or marriage veil that strangles her – smears her face with lipstick, covers her head and shoulders in tilak powder or just screams barefaced.

© the artist

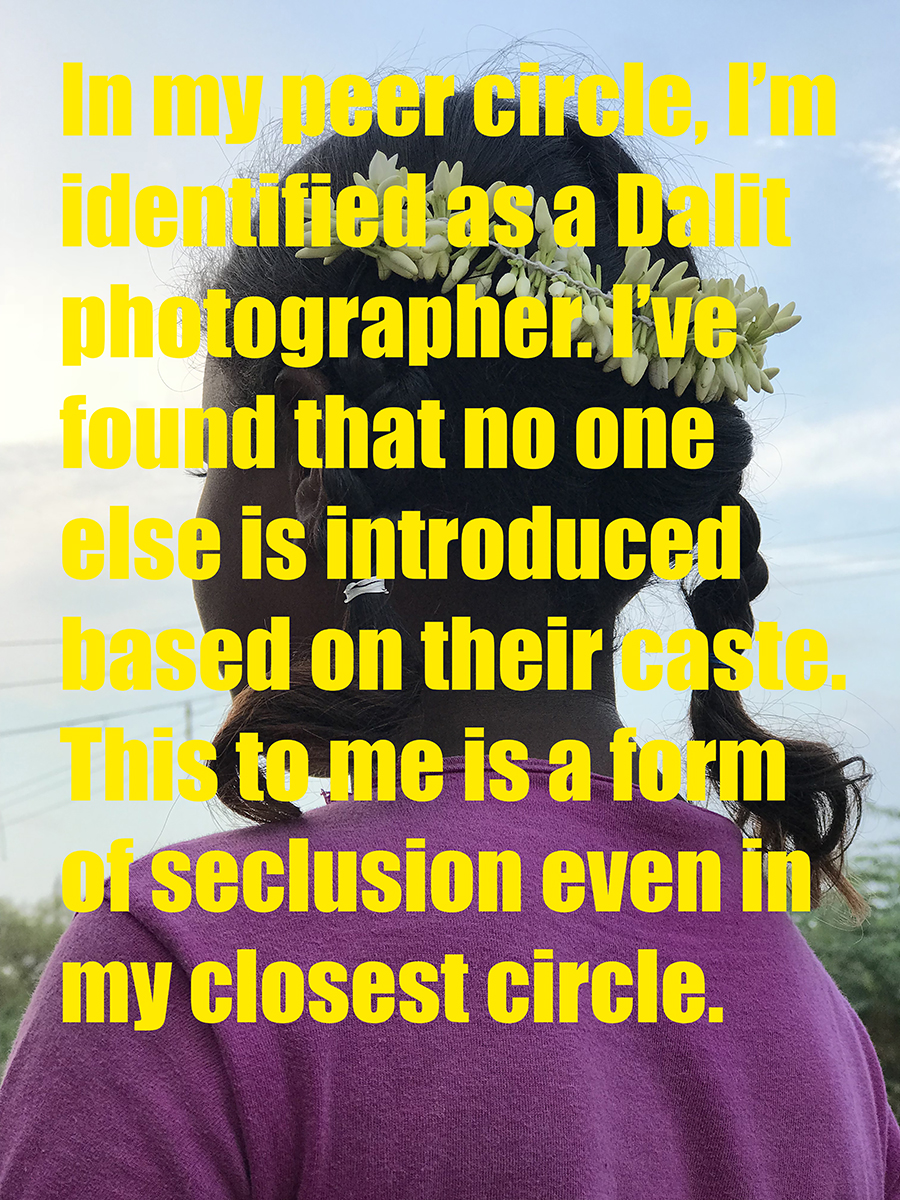

Especially powerful is Jaisingh Nageswaran’s I FEEL LIKE A FISH (2020). It features images of his daily domestic life overlaid with yellow first-person texts that link the isolation of the pandemic with the ‘ritual pollution’ or untouchability of the ever-active, ever-brutal caste system. ‘Being born in a Dalit family in the state of Tamil Nadu, I’ve known what it is to be socially distant,’ one reads. It continues: ‘We

live in a ghettoized community near the local cremation ground. My veins are loaded with the smell of burning bodies and I’ve always been truthful to that.’ It becomes especially poignant given all the images that are coming out of India right now: lines of bodies on stretchers waiting to be cremated and a country lit up with funeral pyres like a macabre Diwali map. In Sean Lee’s Two People, meanwhile, the artist uses photography to try to rekindle his parents’ relationship through touch, to quietly intimate effect.

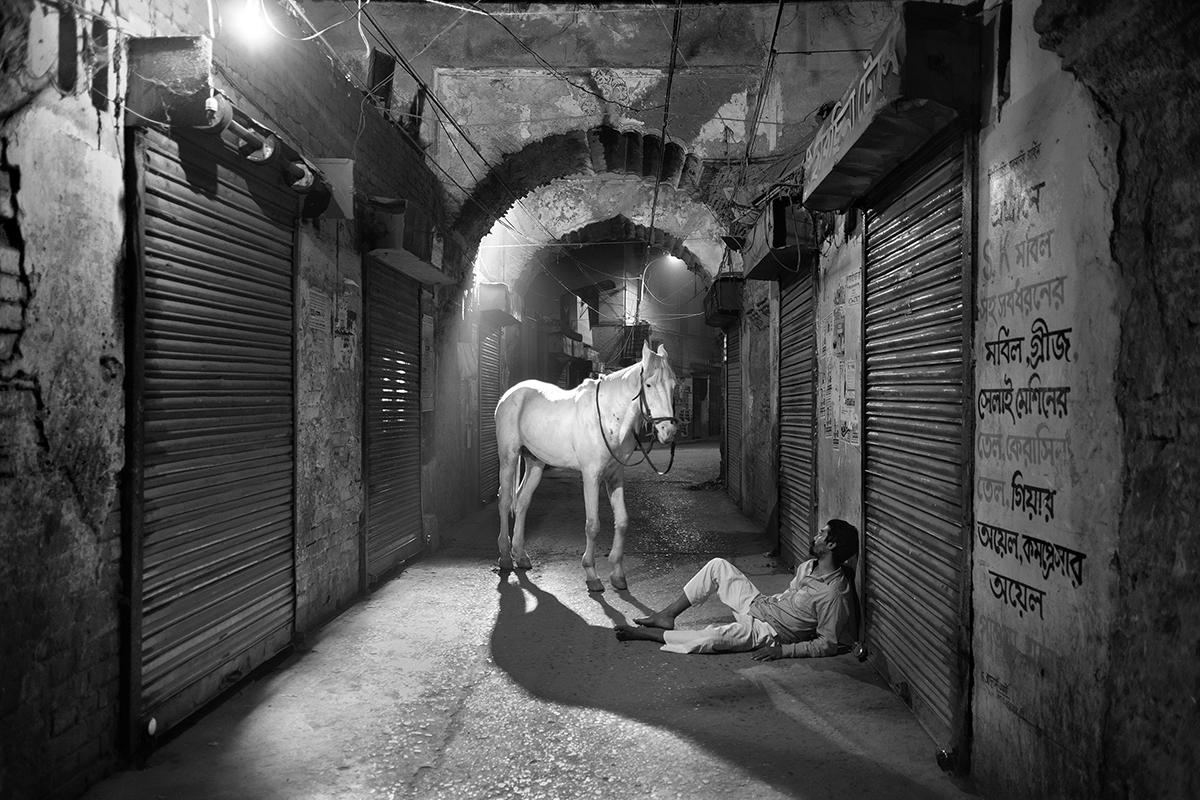

Another highlight is Munem Wasif’s beautifully elegiac Kheyal (2015–18), a short, dreamy film about finding stillness in the nocturnal heart of Old Dhaka. Its imagery – milk being poured over a white horse’s tail and dripping slowly off its fetlocks to pool onto an alley floor, eggs frying and flatbreads puffing – stays with you like a solar afterimage. Its sense of magic meanwhile is reflected in an L-shaped installation of photographs taken by children participating in photo workshops at Anjali House in Cambodia. Here too are images that linger: a lounging cow sporting a Louis Vuitton purse and a pot on its head, a couple and two rotund ginger cats asleep on a quilted maroon mattress.

There’s something nice, too, about articulating relationships to place and to each other that are not defined by borders or citizenship lists. Many participants are regulars on the Chobi Mela circuit, one of many events where people from across the region end up meeting in Nepal or Bangladesh or Sri Lanka, and – this show suggests – perhaps the UAE too. But still one wonders about all that annotation: why not let the subcontinent and all its images speak for themselves?

Growing Like A Tree at Ishara Art Foundation, Dubai, 20 January – 20 May