Steyerl challenges us to recognise the vast scale of AI’s ubiquity and also to realise its ‘artificial stupidity’

When Marshall McLuhan attempted to categorise media along a ‘hot’ and ‘cool’ spectrum in 1964, artificial intelligence was still in its infancy, of interest primarily to programmers and sci-fi enthusiasts. That AI could produce media was an unfathomable idea. Whether hot (film, radio, photographs) or cool (telephone conversations, printed cartoons), McLuhan believed media was ‘an extension of man’, of our eyes and ears. Today, his distinction between hotter, more passive forms and cooler, more participatory media comes across as dated. Our modern attention spans are simply overheated. When social media feeds can be scrolled through at a feverish pace, everything seems to run hot. Is it a coincidence that the dichotomy between a ‘cool’ past and the ‘hot’ present also mirrors the intensifying rate of climate change?

This thermodynamic language is employed throughout Medium Hot: Images in the Age of Heat (2025), a new essay collection by the artist and filmmaker Hito Steyerl, to scrutinise the technological forces accelerating entropy in both the virtual and natural worlds. Steyerl has worked closely with artificial intelligence and machine-learning technology in her artistic practice, years before AI broke through to the mainstream. Her multimedia installation This Is The Future (2019) used AI to produce a series of digital plants, which bloom and evolve based on predictive algorithms, and her film Animal Spirits (2022) contained computer-generated animations. Medium Hot details Steyerl’s image-making experiments from 2017 to 2024, when her increasing familiarity with AI led Steyerl to fixate on its deleterious consequences, as the technology began to seep into every aspect of the media landscape.

Medium Hot’s title riffs on Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool (1969), a film about a television cameraman who becomes mired in the political turmoil he is tasked with documenting. Wexler’s cameraman is a proxy for television’s cool disaffectedness. The character is so callously inured to any kind of firsthand violence that his first instinct is to record it. The film probes the ethics of TV production by incorporating real-life footage alongside fictional scenes. In doing so, Wexler (who was a cinematographer before he was a director) appears to implicate himself in the act of image-making.

To a similar extent, Steyerl raises unresolvable questions about the future of image production in the age of AI, which she believes is increasingly ‘inseparable from da/mage-making’. This kind of pluralistic wordplay is typical of Steyerl, and reflects the multivalent quality of her intellectual project. As AI becomes incorporated into most tech products, creative workers are at risk of becoming dependent on ‘proprietary pipelines’, Steyerl argues. Their ability to work, as well as their personal data and projects, will be inevitably linked to big tech companies like Adobe and Google. Of particular concern is how any content on the internet, regardless of copyright protection, can be absorbed into training data without the creator’s permission. As a result, artists may find themselves unwittingly fooled or forced into the AI ecosystem. Take Adobe’s terms of service, updated last February, which suggested that user content may be used for machine learning, leading to alarm among its users.

Steyerl’s essays tend to follow a deterministic structure, beginning with a narrow focus on a single idea or concept before branching out towards its broader political and technological implications. She returns throughout to the natural resources and human labour that power AI’s virtual infrastructure. AI’s computational capabilities are not siloed to the virtual realm, Steyerl reminds us. The technology has a hefty energy footprint, something that Big Tech has worked to hide. Medium Hot addresses the exploitative and energy-intensive acceleration of the AGI (artificial general intelligence) ‘arms race’, as Steyerl puts it, that is rapidly increasing the carbon footprint of corporations like Microsoft, Google, and Apple; how AI-based tools by military software providers are being tested, refined and deployed in war zones; and how AI’s seamless interface is maintained by an underclass of human workers performing ‘cheap clickwork’, sometimes directly out of conflict regions like Syria and Palestine. ‘While data-based cultures are stagnant, they still move everything else around them,’ Steyerl writes. ‘They heat atmospheres, move people, and burn through resources.’

No doubt these systemic analyses are persuasive, wide-ranging and deeply researched. But in striving to be comprehensive, Steyerl can also needlessly circle around crises. In her ‘Mean Images’ essay, for example, she briefly mentions the AI firm SenseTime, which produced the surveillance software used by the Chinese government to monitor Uyghurs, in a discussion on the eugenicist history of statistics and its role in facial recognition technology, before moving on without further interrogation of the state-sanctioned atrocities it has enabled.

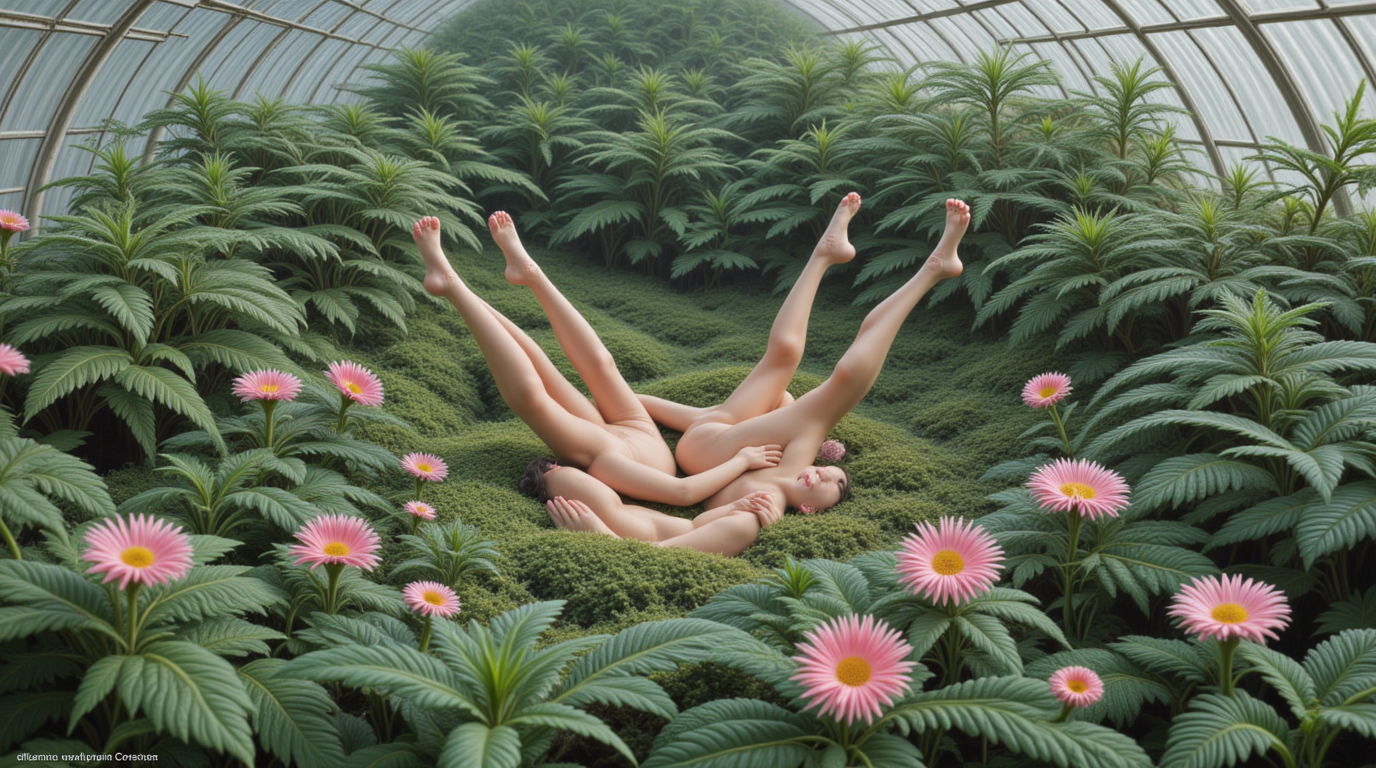

Steyerl is most compelling when she leads with the expertise derived from her own artistic experiments and encounters within the artworld. These range from the responses Steyerl prompted from ChatGPT in an attempt to ascertain whether machines can produce aesthetic judgements, to ‘Twenty One Art Worlds’, an essay formatted as a choose-your-own-adventure game set within the art world. And in ‘Knuckleporn or Phocomelia’, Steyerl explores why image generators fail to faithfully render human anatomy, drawing parallels to medieval art. Here, Steyerl fixates on the regressive tendencies of machine-generated images; their monstrous mistakes are simply ‘a reflection of the social constellations’ of visual elements drawn from a data pool of digital-sameness. Eventually, DALL-E, Stable Diffusion and MidJourney will be overrun by slop. AI image generators, then, are nothing more than a thinly-veiled magic trick, operating on the logic that ‘if one just captures “everything”, a real underlying pattern will be captured too’. But this knowledge paradigm is greatly limited, Steyerl argues, as it ‘erases the possibility of capturing something which is not yet already known’. Because they are programmed on probability, predictive algorithms have a stultifying effect on visual culture.

The book’s most salient essays build upon Steyerl’s existing theory of images. In 2009, she published ‘In Defense of the Poor Image’, a treatise on the boom of low-resolution imagery online. The poor image addresses the form of mass-distributed copies, screenshots, torrents and compressed thumbnails. Akin to visual debris, it ‘operates against the fetish value of high resolution’ in a commercial media landscape where high-quality content is increasingly copyrighted and protected. As a result, the poor image has manifold significance. It rejects the image economy’s widespread commercialisation, but also foreshadows an information landscape that thrives ‘on compressed attention spans, on impression rather than immersion, on intensity rather than contemplation, on previews rather than screenings.’

Steyerl’s theory has proved to be prescient. Written before social media became widespread, the essay anticipated the 2010s boom in memes and meme culture writ large. In the 2020s, Steyerl believes the poor image will become an endangered species: soon, most images circulating on the internet will no longer be photographic representations of reality, but data-based renderings that are essentially a programmatic fantasy. The ‘statistical image-making’ of Stable Diffusion and DALL-E derives its contents from large but ultimately incomplete datasets. The generated result is an average composite image that represents the machine’s idea of reality: six-fingered hands, distorted limbs, exaggerated body proportions and eerily smooth foods.

Medium Hot introduces a taxonomic framework for this visual phenomena – one that feels, at times, bloated and frantic in its categorical overlap. ‘Burnt-out images’ refer to works made from AI diffusion models, in which noise, or random data, is added to training data and then removed to generate an image. This diffusion process gives rise to what Steyerl dubs a ‘derivative image’, a term that echoes the concept of ‘derivatives’ in financial systems, highlighting the model’s extractive nature. Consider the derivative image a counterfeit version of the poor image. While the poor image attempts to skirt copyright limitations, the derivative image’s condition for existence is predicated on ‘large-scale data theft’. Steyerl highlights too the bias embedded in the AI means of production but ultimately resists the proposition that models should be inclusively reprogrammed on the basis that implementing diverse training data would only require more labour from microworkers and exacerbate the problem of data theft. AI thrives on disenfranchisement, contributing to ‘multipolar surveillance and… profound social disruptions’.

It’s tempting to wonder, then, what we should dare hope for. Are there any artist collectives or start-ups resisting this widespread computational absorption? Is there legislation being passed to limit resource waste? Disappointingly, Medium Hot doesn’t cohere into a manifesto for the contemporary image worker – the artists, photographers, actors and creative laborers whose work is being subsumed into training data as their livelihoods are increasingly automated. In fact, Steyerl seems altogether resigned to the fact that her work has already been pilfered by AI. ‘I don’t really care that much. If anyone wants to automate me, just go ahead,’ she joked in a 2023 interview. Indeed, Steyerl is more comfortable exposing the exploitative hijinks of machine-learning systems than proposing alternative modes of resistance. She speaks to the necessity of protest for workers to wrest back agency from tech monopolies, likening the 2023 Hollywood writers’ strike to a powerful form of ‘reverse entropy’. But beyond her verbal endorsements of collective organising, Steyerl offers little else against the impending tidal wave of AGI implementation. ‘Things are moving so quickly that the swift obsolescence of any current ideas about them is unavoidable,’ she writes in her introduction.

Steyerl has directly worked and tinkered with the technologies appraised in Medium Hot throughout her career. She resists the didactic instinct of recent books on internet culture — writing that either absolves the reader of their own helplessness or suggests changes in individual behavior that have little bearing on the systemic issues at hand. Yet, her seeming resignation towards AI sounds oddly familiar, even as her writing exists in stark contrast to the wave of consumer-friendly books on AI, penned by both skeptics and enthusiasts alike.

Steyerl challenges us to recognise the vast scale of AI’s ubiquity and to realise its ‘artificial stupidity’ by disentangling its inner workings. This reminds us that image-making has always been illusory. The camera’s history is fraught with visual tricks, misconceptions and self-deceptions. Recall how in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966), the photographer’s search for truth collapses into grainy ambiguity, exposing the limits of perception and the instability of the real. Steyerl’s work reminds us that no one, no matter how much they resist, exists outside the infrastructures of computation, caught in the blur between representation and extraction. Our visual culture may be shifting toward probabilistic abstractions, but what remains crucial is a strong ethical commitment to staying with reality.

Terry Nguyen is an essayist, critic and poet from Garden Grove, California