Corporate control and idiot iconoclasm are teaching us to distrust our own aesthetic sensibilities

We live in the era of Big Platform, where corporate control and shareholder-panic meets the paranoia of an online, insomniac minority. Art and culture are to be controlled, and expression of all kinds is deemed either ‘good’ or ‘bad’ according to the ever-changing, anarcho-tyrannous edicts of our Tech overlords, who take their cue from the most hysterical among us.

Attention is finite: but there is a surfeit of things to watch, hear and read. In the information age, you don’t need to burn physical copies of things in order to remove them from public circulation. Rather, you can simply ‘deplatform’ them. In recent weeks, scrambling to be seen to respond to the Black Lives Matter protests, multiple broadcast platforms have panicked, taking down films and comedy shows now deemed to be contentious. In the last few years, what is understood to be contentious has become increasingly broadly defined. While conservative and right-wing voices – Alex Jones, Milo Yiannopoulos, Laura Loomer, Louis Farrakhan, for example – but also left and liberal gender-critical women, such as Meghan Murphy – have been chased off social media platforms keen to establish their ‘woke’ credentials, now, even once-mainstream fare such as Fawlty Towers, Little Britain, The Mighty Boosh and The League of Gentleman have all come in for various degrees of opprobrium and removal from the online archive. The range of what counts as acceptable gets smaller and smaller.

But today’s censorship is highly uneven. Porn sites remain untouched, but gender-critical Reddit pages are taken down; you can get hard to poor teenagers having sex on camera, but women discussing proposed changes to government legislation around sex and gender is verboten. It is seriously worth, as a matter of course, asking who wants you to see what, and why. In the meantime, keep hold of all your analogue culture – books, vinyl, DVDs – you never know when something you love is going to get pulled from digital circulation.

In recent weeks, HBO removed the 1939 US Civil War historical romance Gone With the Wind from its streaming service, describing it as a racist ‘product of its time’ for its nostalgic portrayal of slavery and the Confederacy. Now the film has returned, but this time accompanied by a short introduction by film scholar Jacqueline Stewart. In the context of Black Lives Matter and slave-owner statue-destruction it makes sense for HBO to do this: you can now once again watch the film, but you have to be sure to understand the film in a particular way, in its ‘context’; thus HBO still gets to carry the film and yet not be tainted, or potentially ‘cancelled’, for hosting it. Stewart’s introduction is well-balanced and to the point: it draws attention to the absence of any brutal depiction of slavery, the stereotypes of black characters as inept servants, and notes how segregation prevented black audiences from attending the premiere.

But there are at least three implications of HBO’s gesture that are worth reflecting upon, which relate to all platforms whenever they take someone or something down: first, the simple fact of the material power of platforms to remove whatever book, film, image or piece of music is deemed ‘problematic’ at any time; second, the idea that there is a ‘correct’ way to read the cultural products that we are permitted to access; and, third, that the consumers of culture cannot be trusted to think for themselves, but must be told or shown how to understand images, words and sounds.

Controlling access, controlling reception, controlling minds: these mechanisms are never neutral. It is imperative that we get better at asking who is calling for restrictions on what we can and cannot see, hear or read. It’s worth asking who, exactly, doesn’t want you to see this? What are their motives for censoring something or imposing the ‘correct’ interpretation? Amidst all the outrage, the genuine concern to make the world a better place for more people, our own loyalties, predilections and tendencies, and the sympathy we might feel for oppressed groups, we are, above all, being taught to distrust our own aesthetic sensibility and our capacity to think for ourselves.

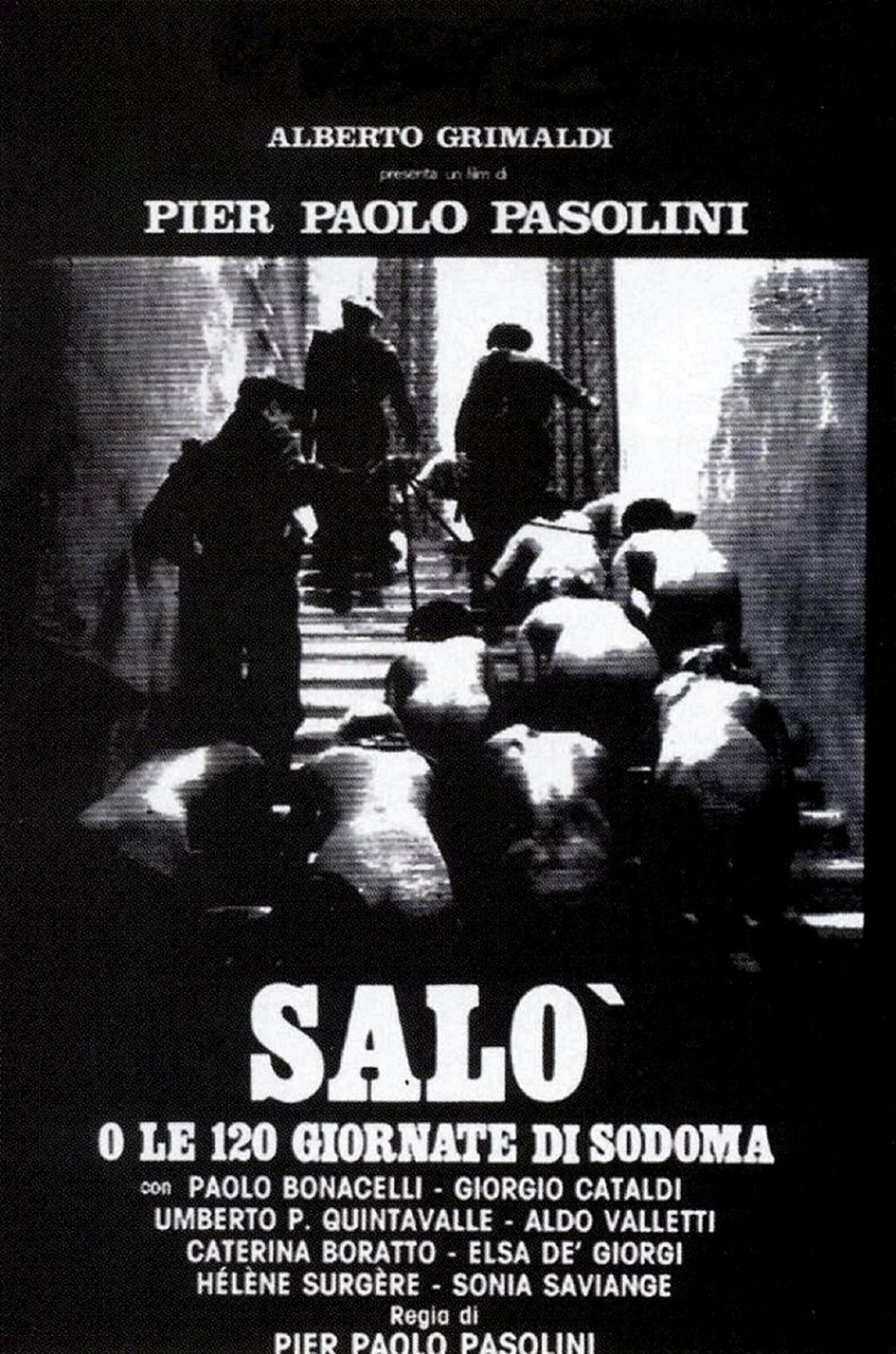

The art of interpretation requires, amongst other things: trust in oneself and the reality of the artist and their work; enough time to see the work from multiple angles; and a willingness to be disturbed in all directions. It can take years to truly understand a difficult piece of work. Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1975 film Salò. Or the 120 Days of Sodom is perhaps cinema’s most superlative exploration of cruelty, power, fascism, sexuality and storytelling, but it is also a brutal, disgusting, terrifying and profoundly disturbing piece of work, subject to various bans on release and afterwards. It repays repeated viewing, and I reflect endlessly, for example, on the claim made by ‘The Duke’ in the film, namely that ‘we Fascists are the only true anarchists, naturally, once we’re masters of the state. In fact, the one true anarchy is that of power.’

Tolerance requires the capacity to imagine or simply to understand that others see the world differently – sometimes extremely – to the way you do. Art and culture are, above all, modes of communication: we can still, and we must, be able to be shocked, moved, disturbed. To imagine instead that the most important thing about art and culture is how to ‘protect’ or ‘shield’ the viewer from the potentially disruptive effects of a piece of art is to envisage a notion of the self that is perpetually fragile, always hurt or vulnerable and in need of permanent protection.

Today it is often those most keen to shield and protect who behave in the most aggressive ways towards art and ideas: we thus find ourselves, all of us the result of the violence and cruelty of history, in the midst of a new culture war in which the freedom to think, feel and express ourselves comes at the risk of economic impoverishment, social ostracism and mob justice.

Authoritarian tendencies never truly go away. Art at the edges will always be a risk, in that it presents back to us everything we are in a mediated form, good and bad. At times, conservative values have threatened art; at others, like now, the left seems in the ascendency, finding offence everywhere, and finding delight in censoring and oppressing.

But under repressive regimes of all kinds, art is vital when it is underground and oppositional: think of the work of Serbian director, Dušan Makavejev, critical of Soviet communism, Yugoslav socialism as well as American imperialism; of punk’s refusal of a temporality that only appeared to embrace conservative values; of feminist art’s repositioning of desire and pleasure.

It is art that reveals to us, as if in a flash, the absurdity of the status quo, the mechanisms of domination, how we find ourselves caught in webs of unfreedom of all kinds, even, or especially those, that purport to be ‘on our side’.

Ask yourself what you would do, and who you would be, if you were truly free. Only with an image of freedom in mind can you begin to trust your judgement, aesthetically and politically. The mechanisms of censorship are often insidious and come today, for example, shrouded in the language of kindness, compassion and the pain of the other. Censorship is frequently pre-emptively internalised – we do not always need platforms to punish us when we say the ‘wrong’ thing; sometimes we know in advance what it is we should or should not say. But art, like life, is often very difficult: It is not up to others to tell us how we should interpret either. We can, and should, trust ourselves (and each other) to deal with the potentially devastating aspects of both.

Nina Power is a writer and Philosopher.