What do we lose when major chunks of the past are excluded or erased from pedagogy?

Tipu Sultan (1750–99), or the ‘Tiger of Mysore’, could hardly be called the most influential of Islamic rulers to have reigned over parts of India. The Mughal Empire (sixteenth to mid-nineteenth century) controlled most of the subcontinent; the Deccan Sultanates (sixteenth to late-seventeenth century) in the south left a far more influential and lasting impact on the political landscape and socio-cultural life in the country. Tipu’s rule over the Mysore region has had a lesser impression on culture in what is now the state of Karnataka. Neither was Tipu among the most ruthless rulers in history. His policy of forcibly converting people to Islam after defeating their king, desecrating places of worship as a way of humbling the enemy and removing sources of power and identity were common political strategies practised by warring kings of all faiths, across all India’s kingdoms and beyond. Tremendously wealthy as it was, Tipu’s kingdom was not the richest of his time either, though in the few peaceful years between the many wars he fought, he was well on his way to making Mysore the centre of a formidable empire. That he was a devout Muslim ruler of a mostly Hindu populace was again not unusual; like other kings of his time, Tipu’s realpolitik was a necessity, rather than a personal kindness towards his subjects.

What set Tipu Sultan apart from most of his contemporaries, however, was his quick recognition of the East India Company’s expansionist ambitions and his determination to drive out the British from the borders of the subcontinent. Unlike in other royal courts, in which ambassadors of the Company were welcomed, no European was allowed into Mysore without an invitation. For this, he was subjected to a villain-making campaign by officers of the Company courts. More than 200 years after his death, the remnants of his vilification continue to dictate how his history is perceived in India.

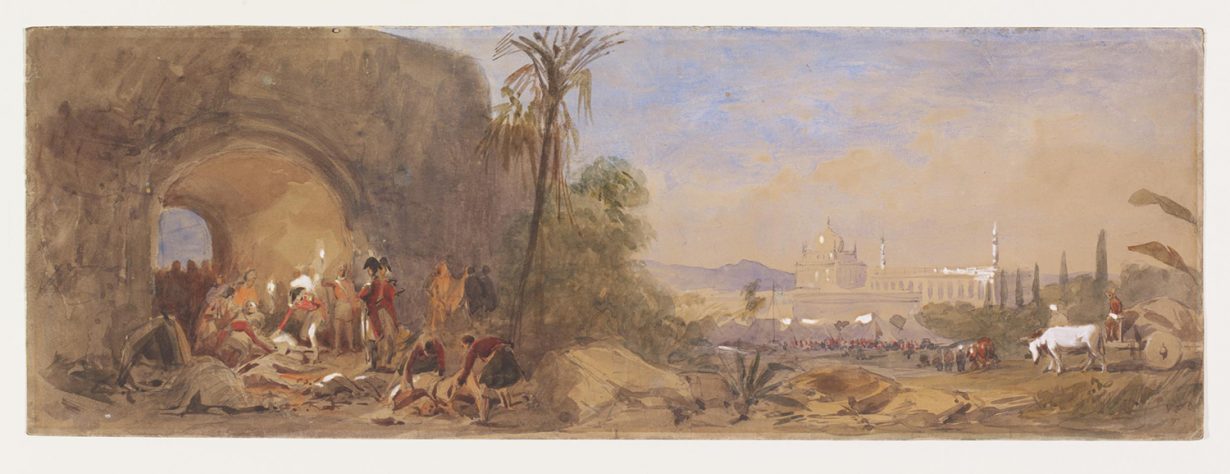

The extraordinary loot from the Siege of Seringapatam (present-day Srirangapatna, 130km from the state capital, Bengaluru) in 1799, when Tipu was killed, is today enclosed in royal collections and museum displays across the British Isles. Tippoo’s Tiger, an organ in the shape of an almost lifesize wooden tiger mauling a European soldier that, semiautomated, produces sounds that mimic the dying man’s moans, occupies pride of place among the collections of London’s Victoria & Albert Museum and remains one of its most famous exhibits. With museums beginning to acknowledge, however reluctantly, the colonial pasts of their collections and the violent events that led to the objects leaving colonised shores, it is timely too to examine how manufacturing consent and an eighteenth-century PR smear campaign have left Tipu’s legacy open for continued erasure in today’s India.

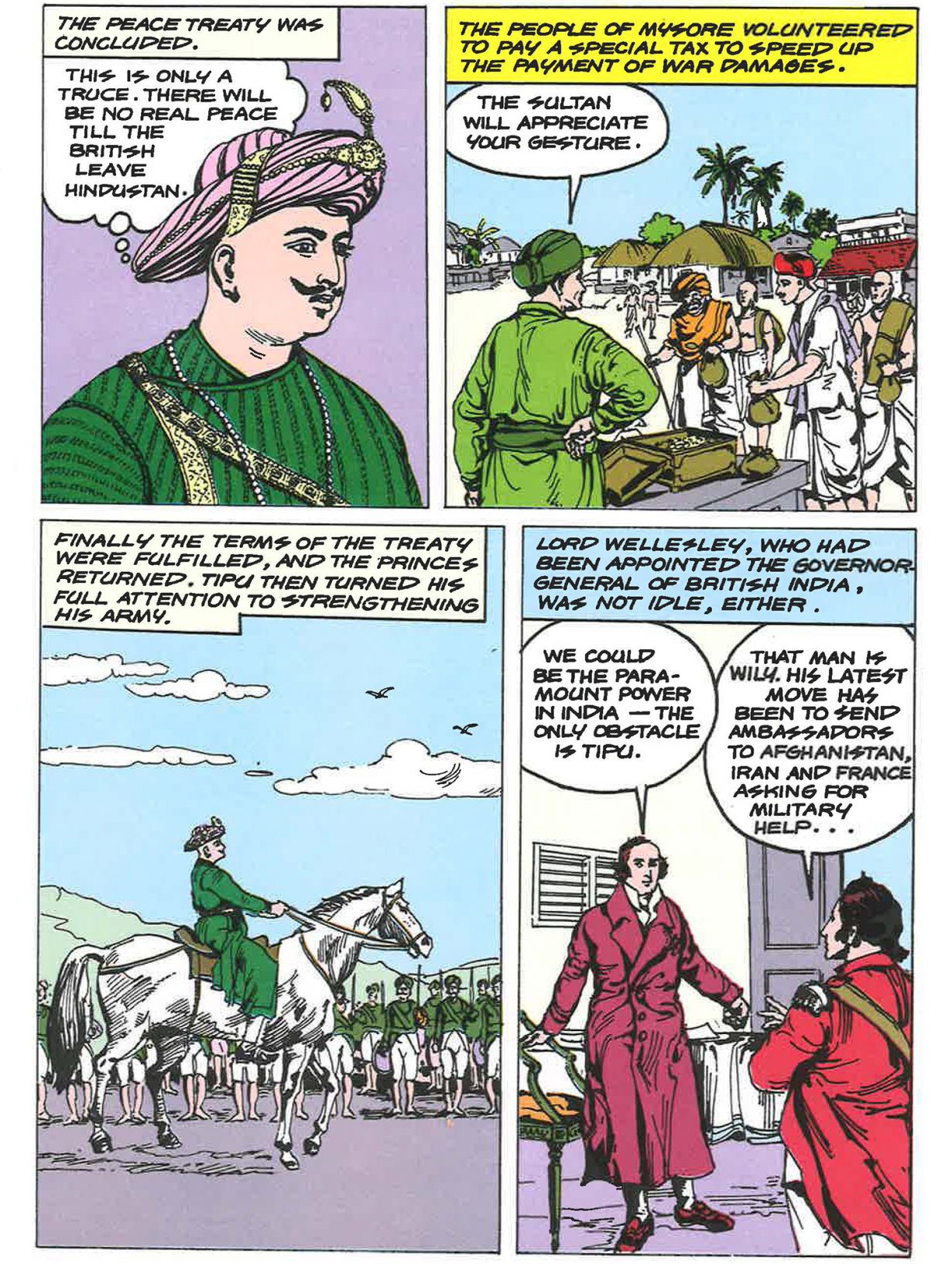

Tipu’s father, Hyder Ali, was a professional soldier under the Wodeyar kings of Mysore who rose up the ranks and became a ruler during the 1760s. Fuelled by great ambition to expand his kingdom, and later with the motive to halt the progress of British forces in the country, he would continue waging wars against the imperial army and other kingdoms in the south for the rest of his life. In a relatively brief 17 years as king, Tipu would go on to seek alliances with Turkey and France, as well as reaching out to kings in the nearer vicinity. In fact,

Napoleon’s ultimately disastrous campaign in Egypt was part of his larger project to reach India and ally with Tipu against forces commanded by the future Duke of Wellington in order to weaken British expansionism. One can only speculate on the progress of world history if such an attempt had come to fruition.

While the four Anglo-Mysore wars proved somewhat successful for the British, what helped turn the tide was a campaign to portray Tipu as a bigot and a tyrant to subjects of the empire back home. For nearly 30 years, Tipu’s supposed rule of terror was at the forefront of public consciousness via vivid and, more often than not, embellished reports from Mysore. When he finally died in battle at the end of the eighteenth century, soldiers led by General Harris were given free rein to loot the palace grounds. Apart from immense quantities of gold, precious books, weaponry and other treasures, the looting included Tipu’s throne, which by all accounts was so grand and large that it could only be shifted by breaking it into pieces. One of several finials, encrusted with precious jewels and in the shape of a tiger’s head – Tipu’s favoured symbol of identity and power – and a jewelled huma bird that sat atop the canopy of the throne are amongst the treasures in the Royal Collection Trust today.

Were Tipu and his father two of the greatest patriots who fought what should be described as some of the earliest wars for Indian Independence, decades before better-known wars against the British? A comic published by Amar Chitra Katha, one of India’s most-read publishers of graphic novels, certainly thinks so. As did a yearlong drama series called The Sword of Tipu Sultan that aired on Indian state television in 1990–91. Or was Tipu another especially ruthless bigot who needed to be removed to save the region from religious fascism? The reading of Tipu’s legacy today by political parties and in majoritarian public consciousness rarely veers towards a greyish middle-ground between these poles that accommodates the layered and complex rule of this man.

Under the current Hindutva-driven policies of rightwing governments both at the centre and in the state of Karnataka, Tipu Sultan’s period has been subjected to further erasure from history textbooks. The day after a Bharatiya Janata Party-led government wrested power from a coalition government late last year, Karnataka’s chief minister, B.S. Yediyurappa, announced that chapters on Tipu would be removed from school history-textbooks. Following uproar from historians and opposition parties, the decision has currently been put on hold. The Indian National Congress, one of the oldest political parties in the country, functions under relatively progressive and secular policies in comparison to the overtly right-leaning BJP that in recent years has pursued a hardline Hindutva agenda. In 2015 a decision was taken by the state government of Karnataka, then led by the Congress party, to celebrate Tipu Jayanti, the birthday of Tipu, on 10 November each year. The celebration was cancelled after the BJP took power in 2018.

Tipu Jayanti has been a contentious issue ever since: in the festival’s maiden year, there were widespread violent protests in the districts of Kodagu, Dakshina Kannada (both in Karnataka) and parts of Kerala that led to three deaths. In his lifetime all three regions had been invaded by Tipu and/or his father and were sites of much destruction and violence. In the coffee-growing district of Kodagu, the minority indigenous Kodavas allege that Tipu massacred around 60,000 men from the community during the 1780s when he briefly controlled the region. That there is no historical evidence for this supposed ethnic cleansing and that the overall population in the area (including all communities) would have been less than the claimed death toll are dry facts that rarely matter in religious partisanship.

Even a decade ago, though, Tipu Sultan was only sometimes in the public consciousness. But with India’s contemporary political sphere leaning further and further towards the Hindu right, Islamic rulers like Tipu have become awkward issues that no longer have a place in history. It is in this line that some state governments such as Maharashtra and Rajasthan have begun to gloss over, going so far as to wholly remove chapters on the Mughal Empire from textbooks in the past few years.

Tipu has been variously called a tyrant, fanatic, jihadi, patriot, hero, scholar, as valorous as his tiger. He was undoubtedly a complex figure, but it is important to read Tipu as a ruler of his times, for modern ideas of ethics, policies and belief systems can never be congruent with events from distant centuries. No doubt it makes for sensational news in contemporary settings and evokes emotions that political parties have special uses for in furthering their sectarian agendas. The bigger question here is what do we lose when major chunks of history are excluded or erased from pedagogy. Choosing to unteach major events in favour of promoting misleading versions that are more palatable for the majority is an act of politicising the teaching of history. Just as leaving the uncomfortable bits in is a political choice.

History is never linear, nor is it over. It continues to be written and will always be a political tool. Traumatic as some lessons may be, removing uncomfortable chapters – whether on Tipu, or glossing over the atrocities of the empire – from textbooks is only knee-jerk tokenism, not a blueprint for acknowledging, understanding and perhaps even healing.

In a recent episode on erasures in US history textbooks, British- American comedian and host of Last Week Tonight John Oliver’s thoughts could well apply to the controversial case of Tipu Sultan: “History taught well teaches us how to improve the world, but history when taught poorly falsely claims that there is nothing to improve”.