This autumn, creative workers will be joining a growing army of the unemployed – we need a profound rethink, fast

You have been listening to – or have just missed – the UK government’s latest attempt to assure us that ‘we’re here for culture’. It is not clear who ‘we’ are, but the banal rhetoric of the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport suggests that they see the arts as a source of economic significance and national pride. Above all, they want us to know that its Cultural Recovery Fund is worth £1.57 billion.

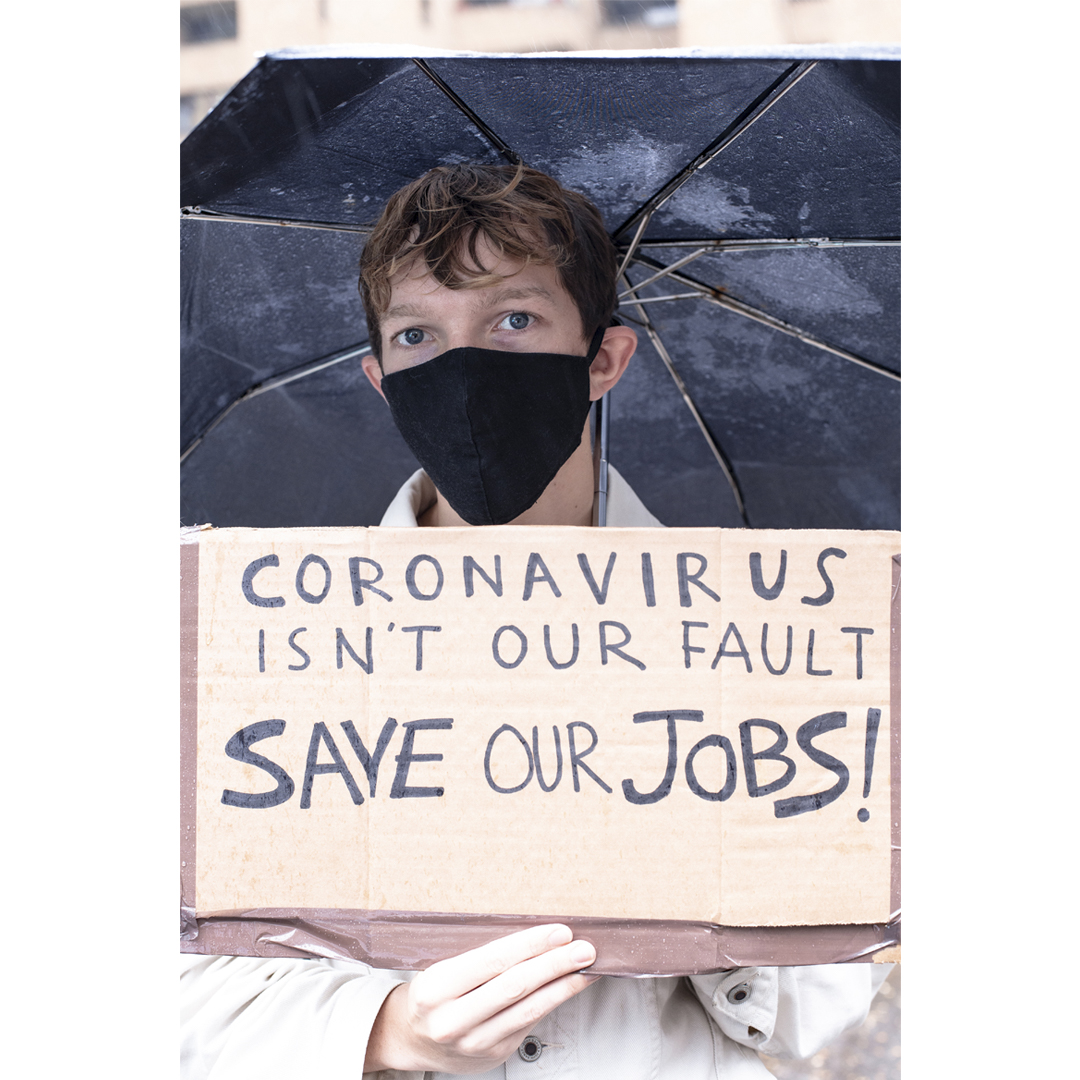

The Office for National Statistics confirms that the arts and entertainment sector has been the worst hit by the COVID-19 crisis. 25 percent of businesses are not trading at all; 41 percent have seen their turnover fall by half. Reserves are going or gone. £1.57 billion is a lot of money, but as the DCMS parliamentary committee recently pointed out, it – like the government’s Cultural Renewal Task Force, which is supposed to decide when it is safe to go out to play again – has come ‘too late for many’ in the arts.

It also betrays the DCMS’s ignorance of the way the cultural economy works. According to its Secretary State, Oliver Dowden, the fund is primarily to protect the ‘crown jewels – the things that really define us as a nation.’ More plausibly, they define what the Tories define as culture.

Large as the sum appears to be, it does not compensate for the 35 percent fall in Conservative government support for the arts in the last decade. Like the NHS, the arts have been weakened by austerity. It also exposes the folly of a policy to drive down public subvention for the arts and drive up their commercial earnings. Cultural institutions have responded to the challenge by commodifying more and accepting less funding, but now enforced closures and social-distancing measures leave them high and dry, in an impossible economic position.

Yet Dowden presses on. In a letter to national museum directors he tells them to ‘take as commercially-minded an approach as possible, pursuing every opportunity to maximise alternative sources of income’. Otherwise – ‘I will not be in a position to make a case for any further financial support’. This hectoring will not make it any more likely that private philanthropists will come to the rescue. The ‘American model’ will not work here – any more than it is working at present in America where philanthropically-funded museums in particular are suffering.

Meanwhile, Arts Council England, made responsible for distributing an initial tranche of £500 million from the fund to support museums, theatres, music and comedy venues, is gloomy. Chief Executive Darren Henley confessed in his blog: ‘this money, significant as it is, will be nowhere near enough to support organisations to emerge from the crisis unchanged.’ The Council’s first act was to look after its own, with £33 million of Council funds directed to some of its larger ‘national portfolio’ clients to keep them going until… September.

They can now apply to the Cultural Recovery Fund which has a longer perspective – all the way to next March. For those who manage to navigate the Arts Council’s ‘Grantium’ application system, the thinking appears to be that you have to be able to prove you were solvent before the crisis, and will be solvent in March 2021, provided you do nothing risky before then, such as trying to function at uneconomic audience capacities.

It would be more honest to call this a mothball fund. The institutions that do survive will be part of a hollowed-out infrastructure. Arts Council England’s ten-year strategy, ‘Let’s Create’, launched, pre-COVID-19, in January with fanfares about a more democratic culture, appears to be still-born, as the government rescues the ‘crown jewels’.

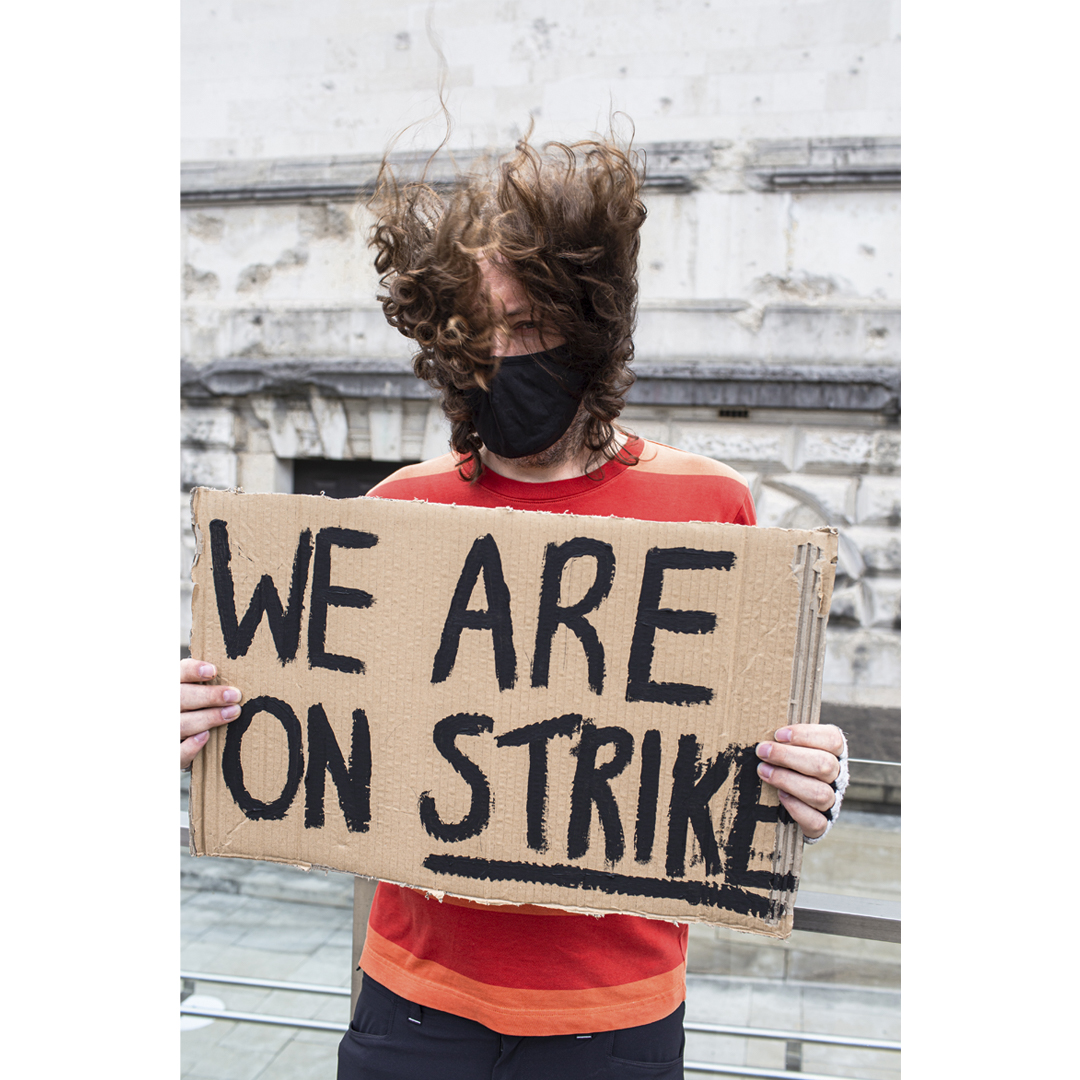

For those who actually create the arts, things can only get worse. The furlough scheme, for those lucky enough to have staff jobs, comes to an end in October, as does the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme. As many as 80 percent of those working in the arts and the wider creative industries are self-employed, and many of them fell through the gaps after applying for support. For those in work, organisations like the South Bank Centre and the Royal Shakespeare Company have opened formal redundancy procedures. Darren Henley has admitted the focus of the Cultural Recovery Fund ‘is not on freelancers’. Yet the arts are freelance. This autumn, creative workers will be joining a growing army of the unemployed.

It is clear that a profound rethink – and restructure – is required. Lord Mendoza, ‘commissioner for cultural recovery and renewal’ assures us that his task force has ‘got all sorts of ideas spinning around.’ This does not inspire confidence that they appreciate the social role of the arts in the public realm, where coming together, in galleries, theatres, and concert halls is an essential part of civic life, as is the need for every community to have the means to celebrate, and if necessary, interrogate, its identity.

One idea would tackle two problems at the same time. Even as it protects the crown jewels, the government has been hacking away for some time at the roots of culture, in schools. There has been a 37 percent fall in entries for arts subjects at GCSE over the past decade. The arts in schools are the gateway to the culture we are supposedly here for. There has been a dearth of education of any kind in the last six months. Why not revive the Creative Partnerships scheme (abolished by the Tories in 2010), and send in all those unemployed artists and educators into our schools to help repair the social damage that is being done? The RSC has pointed the way with its Homework Help initiative, deploying its star actors – unable to perform live due to pandemic restrictions – to answer questions from drama students across the world.

In the long term, we need to restore the civic role of the arts. The National Campaign for the Arts’ Arts Index 2020 report calculated a 43 percent fall in local authority arts funding from 2007 to 2018. Aspects of the COVID-19 crisis have revealed the Tories’ ideological dislike of local authorities, but these maintain the local, non-Arts Council funded cultural infrastructure on which, ultimately, the ‘crown jewels’ depend. If the government wishes to ‘level-up’, then it must reorder the balance between the metropolitan centres, especially London, and the rest of the country.

So far, all the government can come up with is an embarrassing and patronising scheme, the ‘Here for Culture toolkit’. In addition to screenshots and videos, it supplies helpful website copy, presumably because it does not trust arts organisations to create their own. Thus, we must write: ‘In the creative industries, the UK leads the world and we can all feel pride in that – especially here [insert organisation].’

Come March 2021, how many creative organisations will there be to insert themselves into Dowden’s good books?