I Loved You at White Rabbit Gallery, Sydney questions whether our most sentimental actions and responses are just projections based on social conditioning

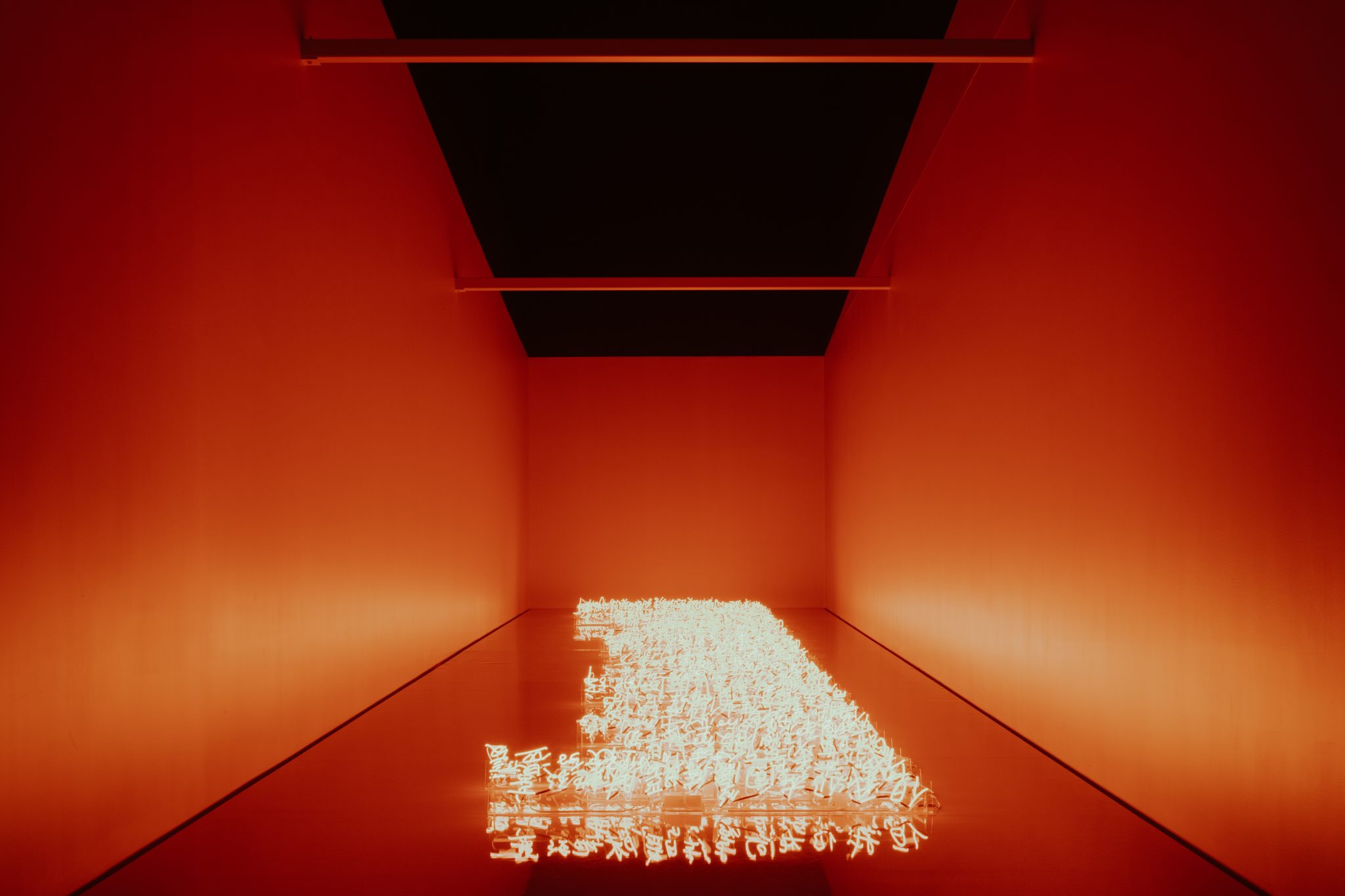

Neat rows of Chinese characters erupt like flowers from a field of gently sloping orange flooring. Rendered in neon lighting and arranged in a rectangular block, the installation appears memorial-like. Visitors who mill around the foyer, or browse aimlessly in the gift shop, can’t help but bask in its unearthly glow. But the illusion of a tribute quickly dissipates when the work’s trickery is discovered: the characters are upside-down. They spell out a poem, ‘Roses Made from Water’, written by the artist’s friend while (according to the exhibition text) high on drugs.

Shi Yong’s installation, A Bunch of Happy Fantasies (2009), part of a group exhibition that brings together 47 works from White Rabbit Gallery’s 2,500-strong collection, calls into question whether our most sentimental actions and responses are just projections based on social conditioning. We’re sold versions of romantic love that can only be sustained by fantasy. Delusions that – in the cold light of sobriety – might just fade.

The Ancient Greeks famously believed in six types of love. There was eros, of course, the passion that can bloom between couples, intense but nearly always unsustainable. I Loved You charts the obsessiveness of romantic love. For instance, in 14 Minutes (2013), one of the show’s strongest works, Hu Weiyi chronicles the way a necklace, a waistband, a sock, emboss his girlfriend’s skin. It’s a study of intimacy that’s also the work of an artist mapping the topography of a lover’s body.

But there is also storge, or the bond that exists between families, and philia, the sense of closeness that draws friends together. The highest form was agape, a universal empathy extended to other people, a compassion that’s also reserved for strangers whose circumstances may be a world away from your own. I Loved You is interested in the many permutations of love, with the works on show complicating the picture of who – and what – we choose to love, and the many ways that affection can take form.

On the first floor, Pixy Liao challenges the rules of heteronormativity, a reflection on China’s veneration of the nuclear family. She and her partner, Moro, pose in a group of striking photographs – part of her Experimental Relationship series (2007–) – that overturn the terms of gendered roleplay. In one image, Holding (2014), she sits in an armchair cradling her naked lover across her lap, gazing at his face intently. His expression is soft, registering a quiet vulnerability. In another photo, Homemade Sushi (2010), Moro poses on a bed, lying atop a roll of towels, his torso encircled by makeshift seaweed, reimagined as lunch.

The tenderness with which Liao’s photographs are made is evident, too, in other artists’ works: for the photographic series Fairy Tales in Red Times (2003–07), husband-and-wife artistic duo Shao Yinong and Muchen borrow the aesthetic of propaganda posters that were popular during Mao Zedong’s political reign, and which were often used to promote and depict ‘ideal’ citizens, to portray children from a Beijing special-needs school. In these photographs – which are hand-coloured – their social status is elevated, the details of their faces highlighted: a boy’s rosy cheeks are smattered with brown freckles, a girl’s rose-tinted glasses are pushed high on her nose, slightly askew. Four largescale paintings by Zhou Zixi, Classmates – Four Policemen (2017), presents four of the artist’s former classmates naked from the chest up. Stripped of their police uniforms, they appear gentle and vulnerable. He evokes their fleshiness in delicate taupe and grey.

Bodies abound in the work of the late Ren Hang, known for his intimate and erotic photographs of friends and collaborators. In one work, a woman is submerged in a bath-tub; holding a straw between her crimson-red lips, her expression is blissful. In another, a man lies in a similar tub, head underwater; a school of goldfish swims a halo around his face. Hang’s work reflects an erotics of looking: one that sees love not as possession or consumption, but as a lifeforce that animates ordinary moments.

Elsewhere, I Loved You looks towards humble attempts to transcend circumstance. On the second floor, Jin Shi’s Small Business – Karoake (2009) is an ode to the street stalls that dot Hangzhou and Henan, where market workers play pornographic videos and hawk counterfeit goods. The brightly coloured installation – a shop-cum-karaoke-bar, strung with lights, in the back of a rickshaw – casts worldly pleasures, however illegal, as a glittering escape from the endless routine of labour. It also seems to be a commemoration of a working community that’s overlooked.

Love is also work, this show reminds us. In The Static Eternity (2012), Gao Rong painstakingly embroiders a full-scale replica of her grandparents’ apartment in Inner Mongolia, a home that’s since been demolished. A pair of cups sit upside-down on a sideboard. Their bed is immaculate. The peeling wall, the texture of the bricks, emerge from the artist’s memory. Love, here, is the labour of attention, which takes form in the slow accretion of details. A fantasy that doesn’t fade away to nothing but can be rebuilt in reverse.

I Loved You at White Rabbit Gallery, Sydney, through 21 November