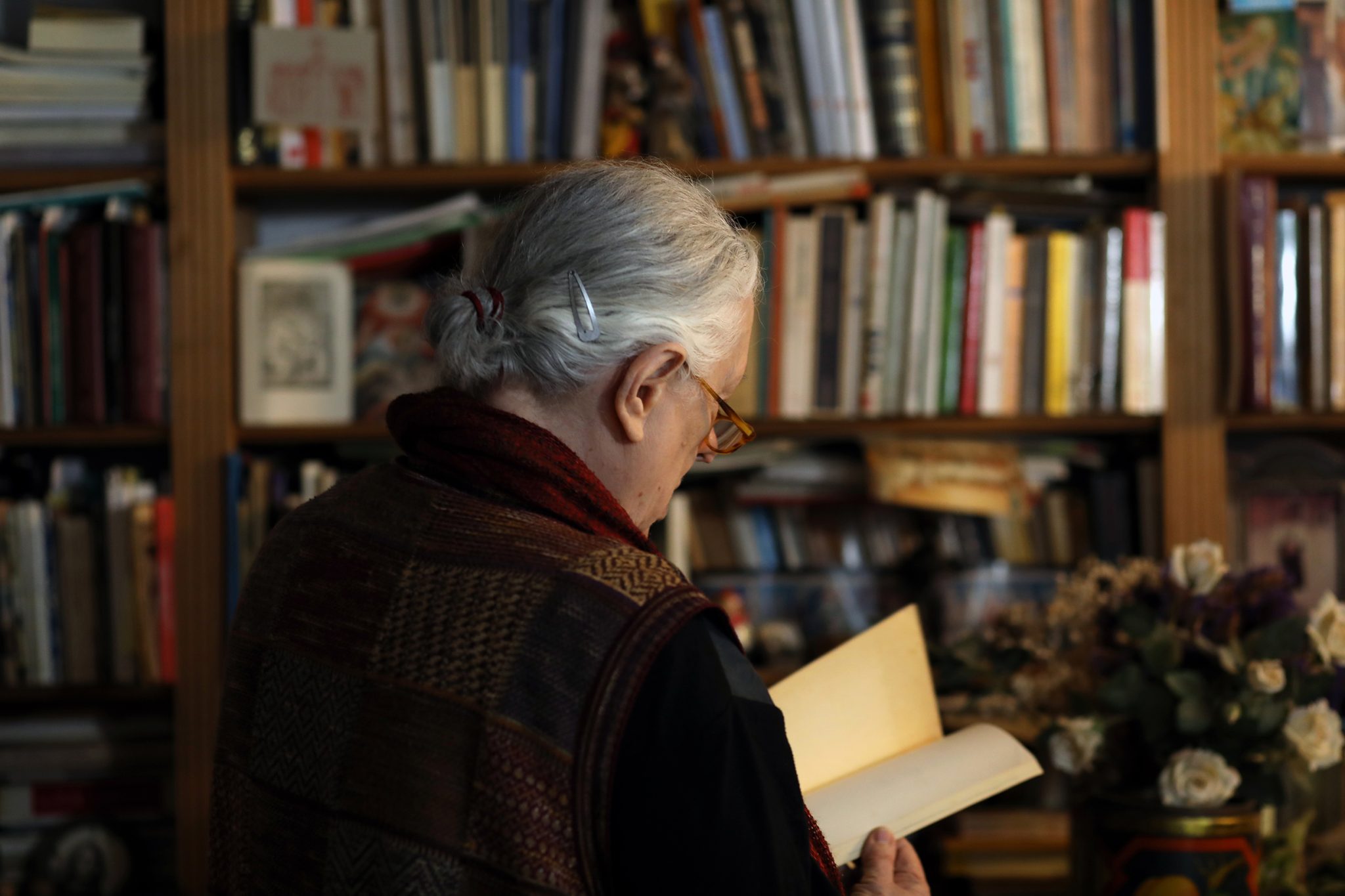

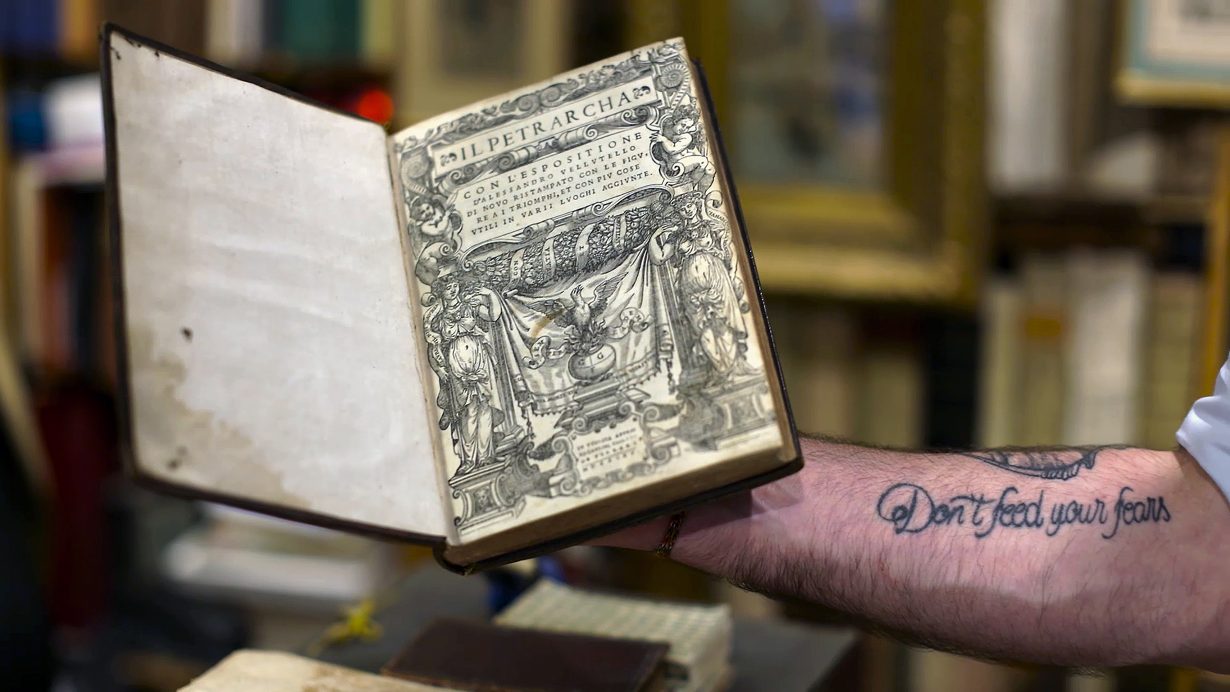

As the artist prepares for the Singapore pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale – Pulp III, a project which offers a testament to archives and books, and an elegy to the beauty of tactility in an increasingly digitized world – she discusses storytelling, underrepresented voices and the endurance of printed matter.

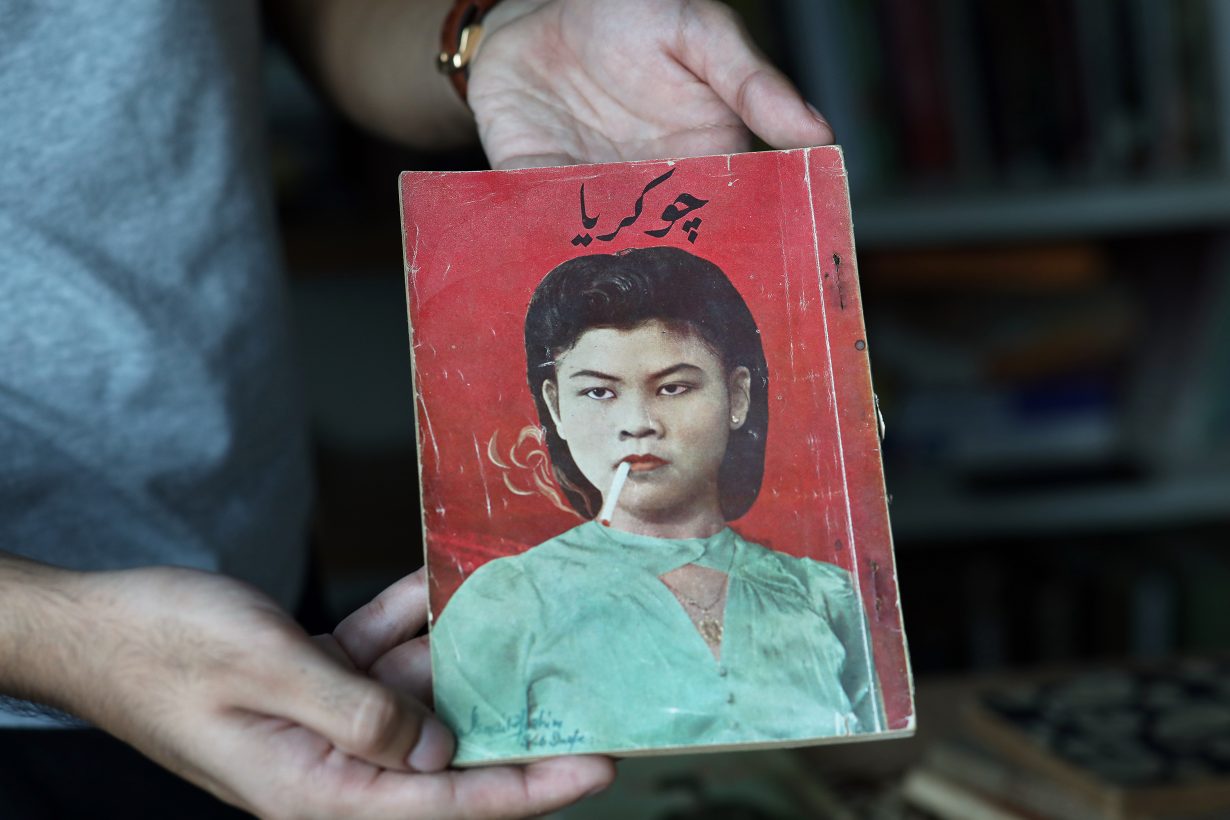

What do you think of the importance of books in providing greater access to stories of and from underrepresented voices?

Shubigi Rao The ultimate point of a book is to be read, parsed, and referenced, for the information in it to be absorbed and to broaden our often-narrow ideas of historical relevance. Unfortunately, libraries (like classrooms) can also be places of exclusion, with women and minority groups being vastly underrepresented. Until we read about knowledge systems, histories, strategies, and structures of thought that have been subsumed by dominant narratives, we will continue to believe in narrow ideas of progress and exploitation of the planet, and capital at the cost of community. Books continue to shape us, and so it is important to include underrepresented voices.

Can you share an example of how a passion for printed matter and books has connected communities?

SR Print communities include not just writers, but the whole ecosystem of people involved in the writing, printing, publishing and distribution of books, as well as readers and those deeply concerned with the future of books and open access, and who will fiercely defend the rights to write, publish and read.

An example of this passion would be the way writers, librarians, and citizens under siege in Sarajevo in the 1990s came together to save cultural heritage and books that were being deliberately targeted, even putting their lives at risk to save books from burning libraries.

The film, Talking Leaves (2022) for Pulp III draws on footage filmed in Venice and Singapore interwoven with prior research – can you tell us about your selection process for choosing interviewees for the project?

SR I usually work alone, often with one region, or critical flashpoint at a time. As I locate people through my research, I meet and film them – mostly solo, because it is important to me to build a relationship over time with some of the participants. I listen to their stories and rely on their recommendations and their suggestions, as well as find new threads that are not available through research-at-a-distance. This work in the field, so to speak, relies almost wholly on word of mouth, serendipitous links, recommendations, and intuitive connections. I find that being indiscriminate at the outset is important, because you never know what stories people are willing to share, and how significant those stories may be.

Could you describe the role identity has played for you as an artist?

SR Very little, to be honest, as I don’t belong to a particular community or linguistic group, and I also moved a lot as a child. Coupled with a more humanist upbringing, my childhood reading habits were indiscriminate and wide-ranging, so I was unable to privilege any singular idea of nationality, ethnicity, nor did I subscribe to one system of thinking or belief. I realise this is a description of being rootless, and a lack, in a certain sense, yet I think it is actually very liberating. This ability to not cleave to a single, enforcing structure of thought or ideological state has contributed to the non-genre specific work I do, or the sprawling long-term projects I undertake.

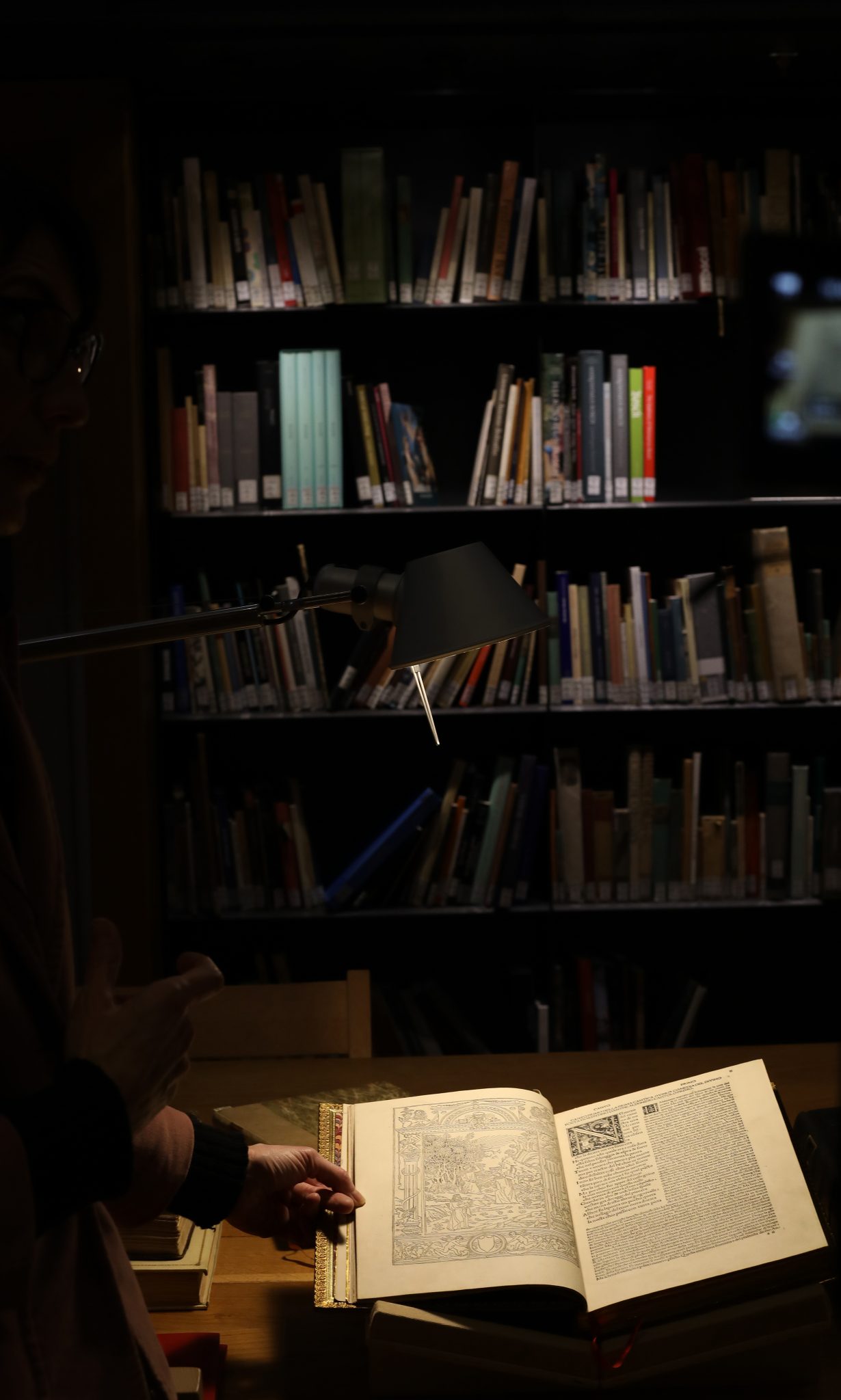

How is lived experience expressed in a book? How is this different from its expression in other media?

SR A book changes our appreciation of time, and because we are not passively receiving images, we conjure up our own. I think of reading as hallucinating time, where we inhabit time spans defined by the writer, and because our brains are required to fill in the blanks more, we populate the text with our experiences and imaginings. We project ourselves into the text and, temporarily at least, inhabit the experiences described within it.

Although incredibly fragile, a book can speak to both ‘tactility and permanence’. Is this more meaningful because we live in transient and increasingly digitized environments?

SR The book form is actually very robust in comparison to digital content. The latter is incredibly fragile, quickly obsolete and unreadable thanks to hardware and software obsolescence, subject to manipulation, censorship, eradication, injunction, corruption, and monetised, conditional usage and control. While both physical and virtual formats have their merits and both are vital in ensuring easy and open proliferation of knowledge, in our lifetimes we have seen the stubborn refusal of books to be supplanted. Again, I don’t think in terms of either/or, as I see both media to be essential, and performing separate but crucial functions. I have to say though, that all those who gleefully trumpeted the death of books since the 1990s and over the last few decades have been proven wrong.

Pulp III: A Short Biography of the Banished Book

Shubigi Rao in collaboration with curator Ute Meta Bauer

Exhibition: 23 April – 27 November 2022

Venue: Pavilion of Singapore, Arsenale’s Sale d’Armi, Venice