Sonic Odysseys at EMST National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens raises the question of what ‘curating’ such a multifarious practice entails

Since his centenary last year, the name of Greek composer, architect and engineer Iannis Xenakis has resounded loudly. There have been festivals and compilations of his music, books about his influence and inventiveness, and here a museum show. The multifarious nature of Xenakis’s practice, though, raises the question of what ‘curating’ it entails. His work can be as large as an architectural pavilion or as small as a circuit board. It can comprise a choreography of laser beams mounted on custom-designed tracks across the ceiling of a Roman baths (Polytope of Cluny, 1971), a multilocational durational event in and around an ancient ruin (Polytope de Mycènes, 1978) or a piece of music (Nomos gamma, 1967–68), all these included in some form in this show. So how to organise and reflect these vastly divergent scales and temporalities, their documentations, their representations?

A possible answer lies in Xenakis’s artistic language. His modernism was not gridded and reductive but synthetic and synaesthetic. His work is a weather system, made up of natural forms broken down into a fluid spectrum. His music and architecture were vectoral, made in the shape of clouds, clusters, branching curves, grains of sound, like lightning and thunder, waves and swarms. This is not a poetic description but a pragmatic one. When at least three adjacent tones in a scale are sounded at once, clusters form; Xenakis’s Keqrops (1986) is full of them. He’s considered the inventor of granular synthesis, a technique for generating new sounds based on ‘grains’ of recorded sound, and he made music from the shape of tree branches developing a concept he called ‘Arborescences’, notably in his piece for solo piano Evryali (1973).

And yet you enter Sonic Odysseys and are greeted by a stiff exhibition design that flatly ignores all of the above. Instead, the all-grey, super-orderly, almost two-dimensional scenography – equidistant office lighting, grids, austere horizontal cabinets – refers, the press release says, to a lab environment. The aesthetic seems influenced by monochrome biographical footage of Xenakis in his working environments, rather than the overall irregularity and dynamism of his work – for example his multicoloured Polytope events (from 1967–84, literal bombardments of light, like an acid disco beamed back from the future), or the branching patterns of Evryali.

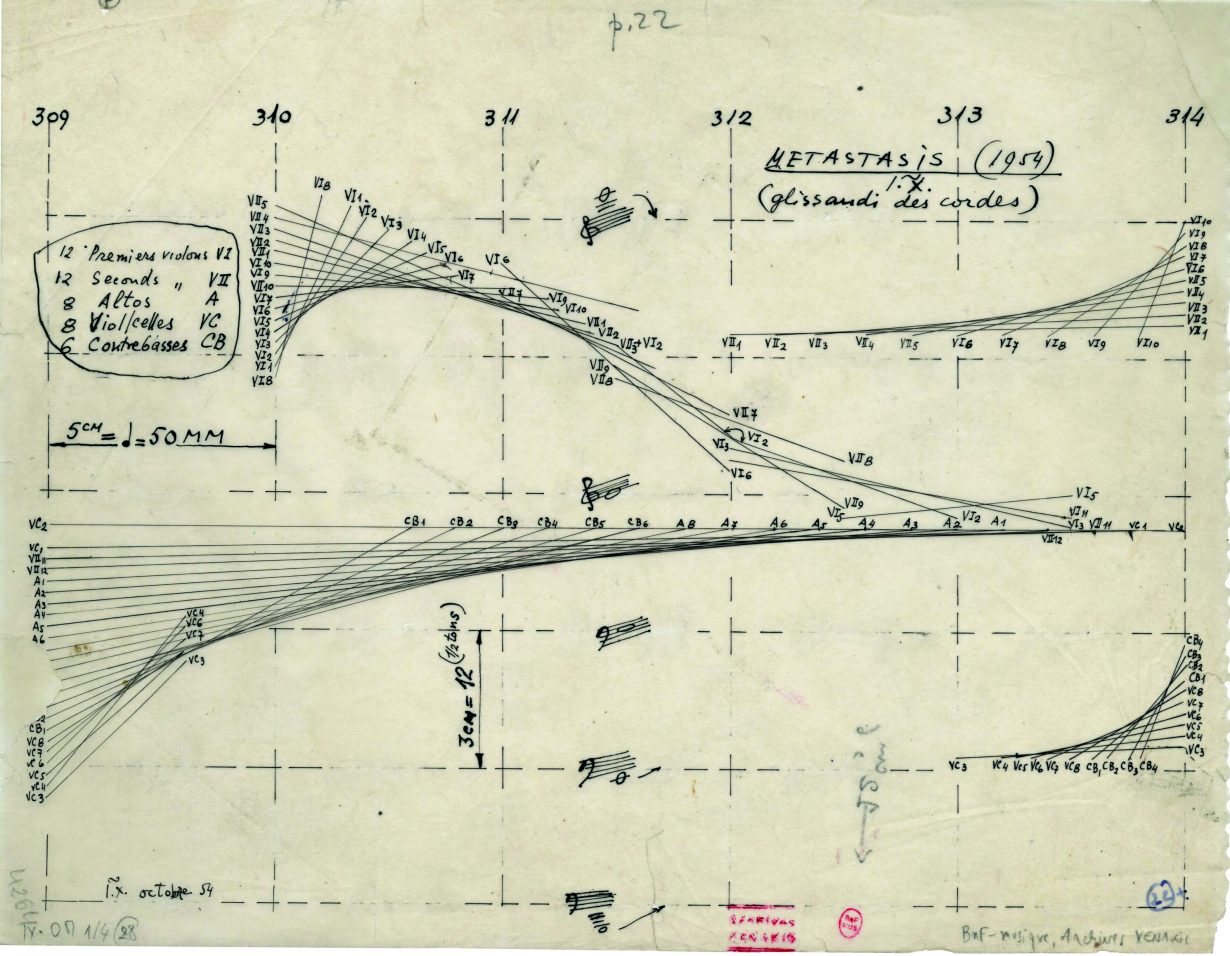

Fortunately, though, if you persist, curatorial acumen starts to break out of the boxes. Documents range from personal letters with both political and emotive gravitas (for example Xenakis’s hand-drafted letter asking to be accepted back into Greece after his long self-imposed exile due to his leftwing activism during the Greek Civil War) to a great selection of lesser-known graphic scores and drawings, placed alongside scores for early and now seminal compositions like Metastaseis (1953–54) and Pithoprakta (1955). The condition of exile and the nostalgia apparent in Xenakis’s deep love of Greek antiquity – through his idiomatic use of Ancient Greek and mythology in his titles and concept-naming – are here brought subtly face-to-face.

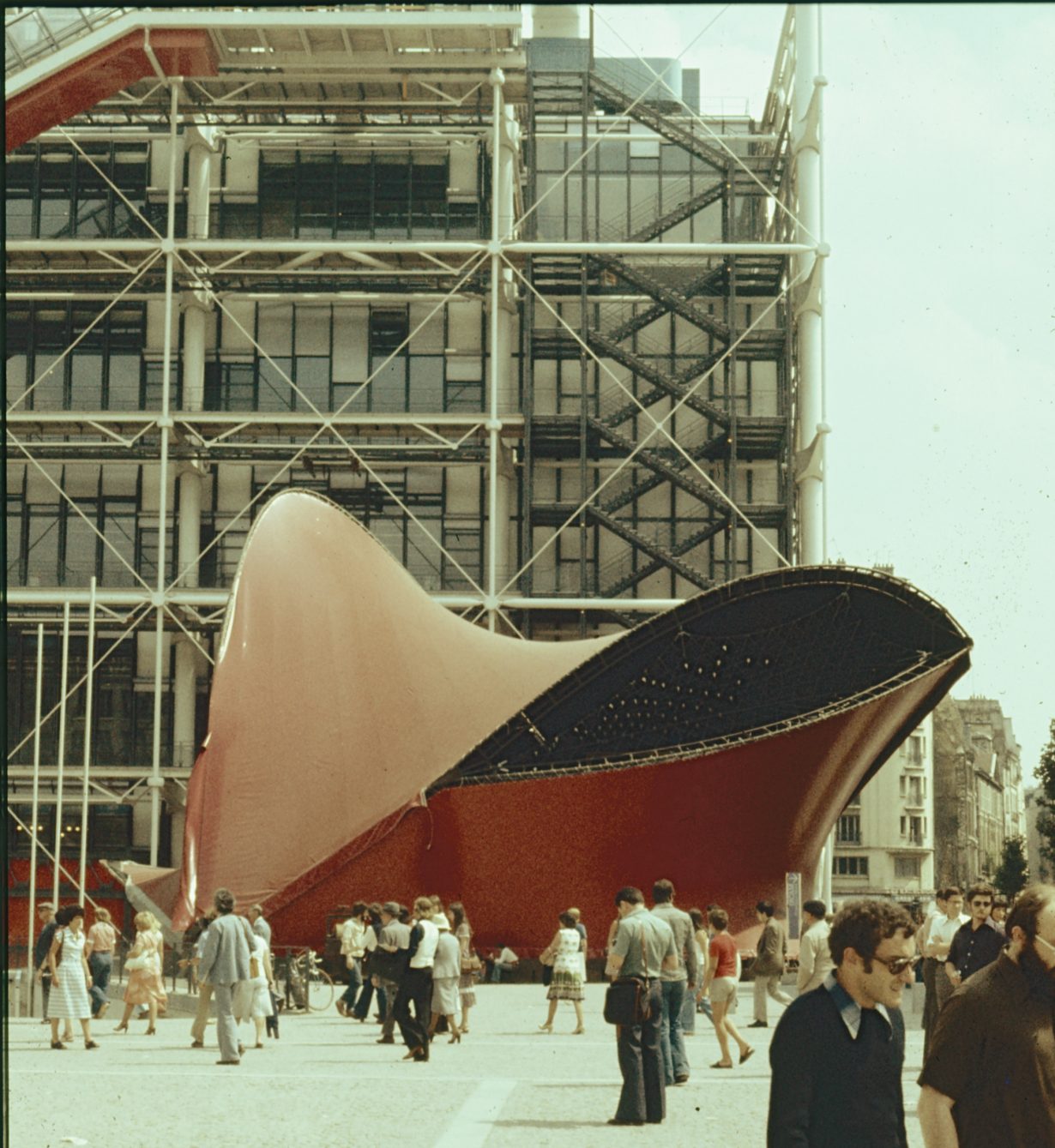

Other cabinets are dedicated to drafts and plans for various Polytope works, a self-invented format for making an event witnessed from one place but taking place in many (the name fuses ‘many’ and ‘place’), each revealing a separate formal assembly, like a multipanelled painting where each segment is in a different vocabulary. This is an endearing insight into how intuitive and unsystemic Xenakis’s work really was, something often overshadowed by the maths he employed to compose music and synthesise sound. Another grid, formed from cubic shelving, presents objects from the composer’s home. The curators balance these intimate effects and documents against others of wider significance, and their coexistence feels unforced and natural. A Triton’s trumpet shell, African masks, a tambour, books and records on Xenakis’s contemporaries, a flint nodule, a Cycladic figurine copy, etc, backdrop two unenclosed objects: a model of the Pavillon Philips by Xenakis and Le Corbusier for Expo 58 in Brussels, and one of Diatope (Polytope de Beaubourg), another multimedia pavilion, created and presented at Paris’s recently inaugurated Centre Pompidou in 1978.

In spite of an exhibition design that could have better emphasised the innate dynamics of Xenakis’s career – personal vision and trauma, artistry and political strife – his wealth of ideas remains visible here. Yet these grey Pandora’s boxes, brimming with rich fuel for the imagination, leave one hoping that Sonic Odysseys is merely a preamble to another exhibition where their condensed worlds expand into the physical and sonic space they fully deserve: a whole floor of a museum, with media-rich, durational representations, to celebrate this unique restless spirit and his huge, still-germinating legacy.

Sonic Odysseys at EMST National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens, through 7 January