A new show at Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin presents paintings as an emblem of commodification – but also a repository, for now, of potential ‘defence’

One of the more interesting – and alarming – recent developments within the infrastructure of contemporary art has been major galleries opening boutique spaces in fancy locales that the non-monied art-viewing public don’t typically access: Monaco, Aspen, St Moritz and others. The shows mounted there, and their constituent works, aren’t exactly hidden from the great unwashed, but most people will only see them online, where the meaning of artworks is increasingly less important than how well they circulate, accrue likes, etc. Such vexed conditions, united under the umbrella term ‘resortization’ by German theorist (and cofounder of art journal Texte zur Kunst) Isabelle Graw, are the starting point for the nine-artist group show she’s curated here. In an accompanying booklet Graw unpacks her theme at length, but at base the show semaphores deep anxiety about whether artworks – particularly paintings – can sustain and convey ‘symbolic value’ beyond their high prices and mobility as images.

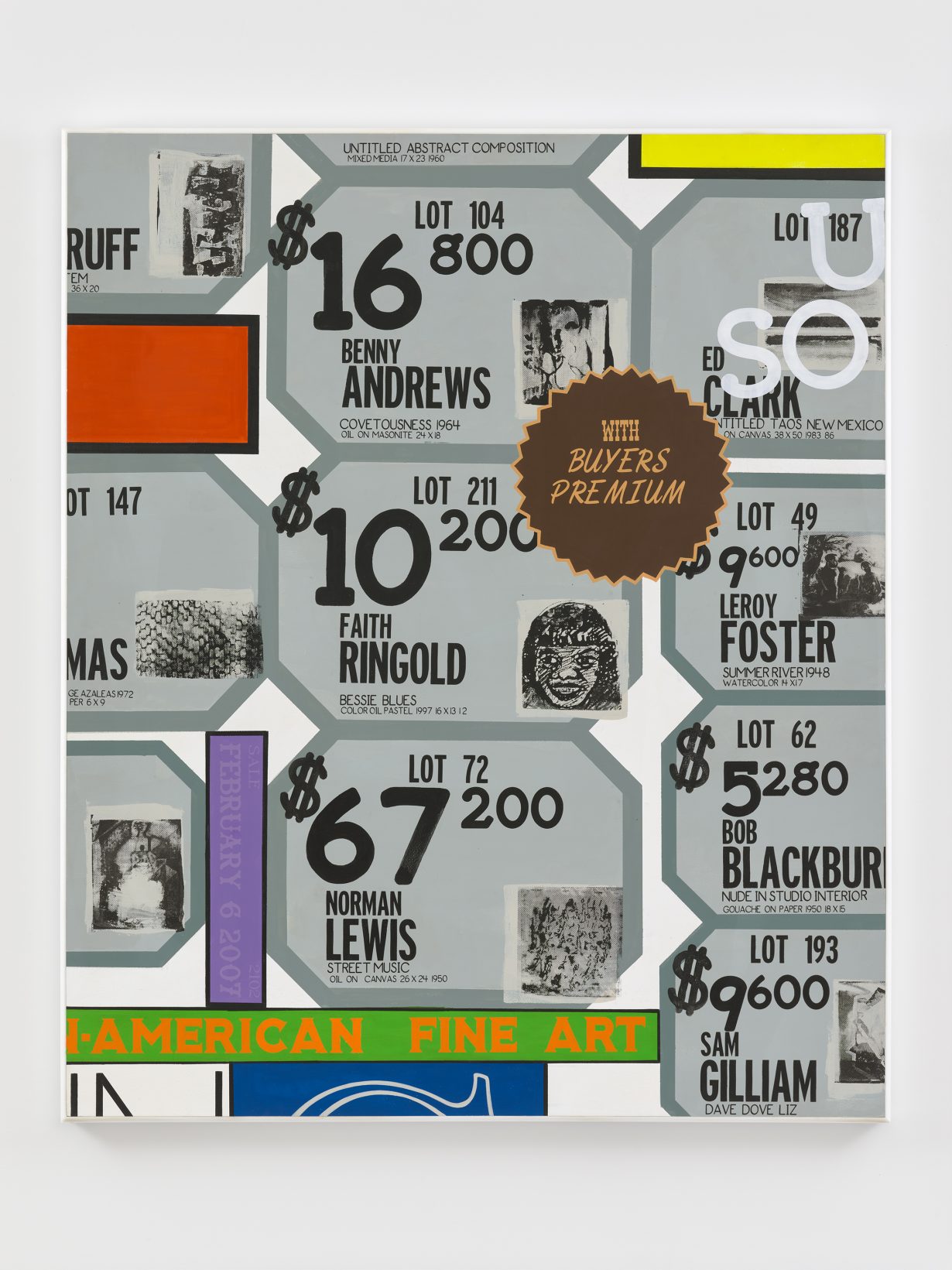

For Graw, whose 2018 compilation of essays The Love of Painting was subtitled Genealogy of a Success Medium, painting is emblematic of this commodification but also a repository, for now, of potential ‘defence’: the artists she’s chosen, in theory, use the form in various critical manners. The most obvious and familiar example might be Kerry James Marshall, whose two History of Painting canvases from 2018 sardonically tabulate, via grids of price tags, the very different auction results for works by white and Black artists ($992k for a Cecily Brown, $10,200 for a Faith Ringgold). Rosemarie Trockel’s American Wall (2023) – a double, Gerhard Richter-ish photorealist portrait of a young Sigmar Polke (albeit painted by Chinese artisans) – meanwhile casts a wide ideational net. Its title refers, we’re told, to how Polke’s generation of German artists had to ‘break’ America to achieve market success; but the doubled image of the artist also suggests two-facedness, and it appears Trockel is alluding here to the increasing revisionist, post #MeToo view of Polke as what (fellow exhibitor) Jutta Koether has called a ‘bad dad’ who bullied others and mistreated women.

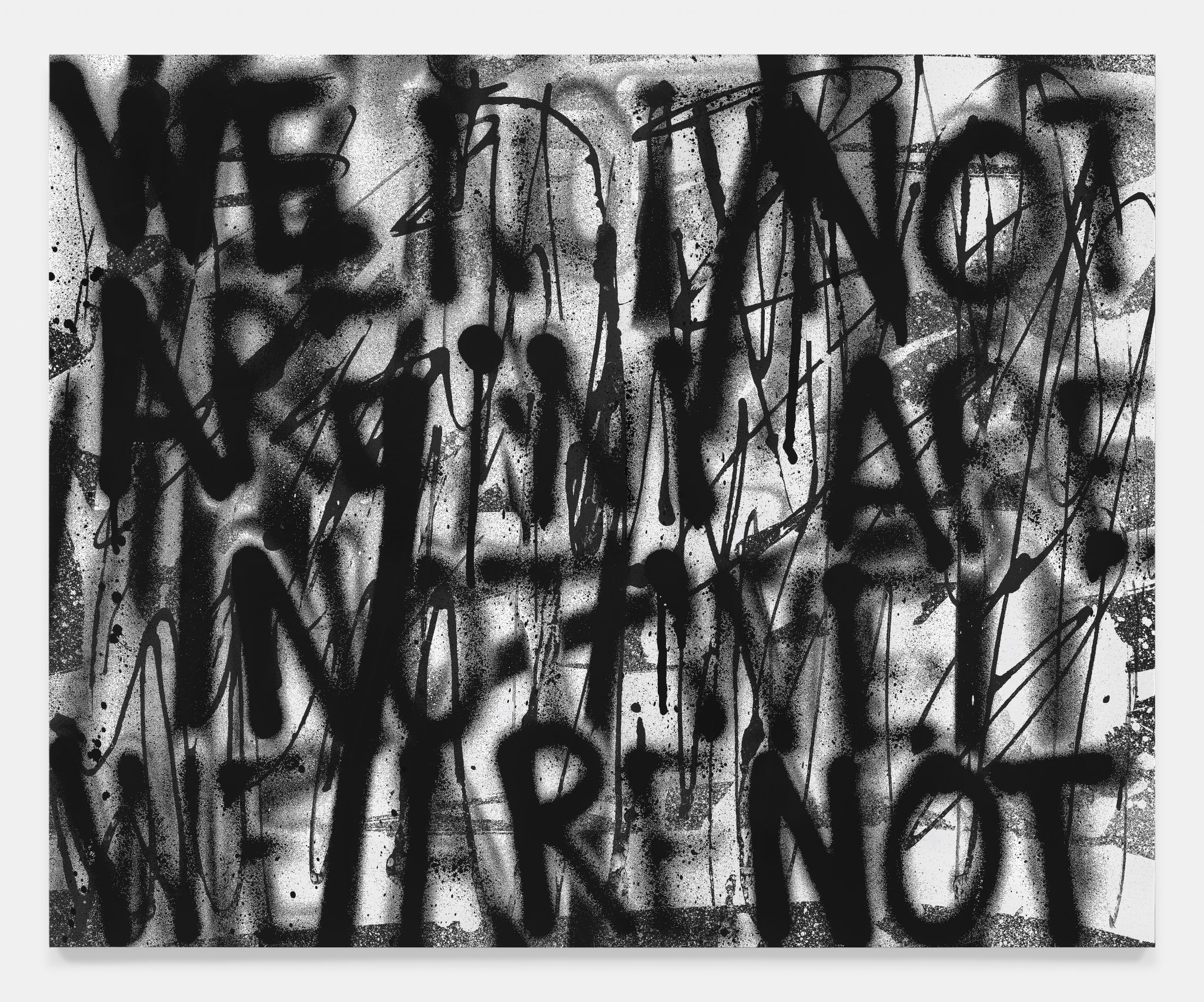

Other artists, at least as presented within this framework, lean into knotty negation: Adam Pendleton’s two monochrome spray-painted canvases, Untitled (WE ARE NOT), from 2022–23, composed of the works’ repeated subtitle – with the second looking like a photo-negative of the first – offer a dovetailed statement and retraction, reflecting Pendleton’s refusal to be pigeonholed as an artist concerned only with issues of Blackness. Two paintings by Albert Oehlen, u.b. B.18 (2022) and u.b. B.15 (2020) – the ‘u.b.’ stands for unverständliche braune, or ‘incomprehensible brown’ – are deliberately dissatisfying murky abstractions dominated by muddy tones. Graw, in her text, points to Oehlen’s noting that as a painter he sometimes feels like ‘a painting program’. The digital encroachment upon analogue painting that forms one half of ‘resortization’ shows up elsewhere, in Avery Singer’s paintings using collaged digital images and spraypaint and splatters applied, we’re told, ‘robotically’, while Valentina Liernur’s murky portraits – one figure holding a smartphone and the other with one shoulder raised – are essentially painted selfies; cue much textual discourse on the contemporary state of the self-portrait.

Many of these artists have been the curator’s hobbyhorses and friends and colleagues for years – half of them feature in The Love of Painting – and In Defense is not exactly an outsider’s plaint. The show is rather a kind of canny, halfway-romantic jigsaw: it allows Graw to showcase her compatriots, along with a couple of gallery artists (Pendleton, Oehlen), and situate them as oppositional, and it serves as theoretical brand burnishing, suggesting that curator, artists and gallery are all high-minded and troubled by how things have shaken out. The cracks and contradictions aren’t hard to see. Max Hetzler may not have a branch in Monaco (think Marfa instead), but Oehlen also shows with Gagosian, whose venues include Gstaad and a private airport outside Paris. Critique, this show suggests, must operate from a place of visibility or risk being completely ignored, and if you appear compromised as a result, that’s the price of doing business.

In Defense of Symbolic Value: Artistic Procedures in the Resort at Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, through 10 June