The palm-sized editions – in mimicking the iPhone screen – capture reading as an experience of additive flux

Before Venice had cruise ships or an art biennial, it made its own fantasies. The isolarii, or ‘island books’, flourished there from the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries: they were a freewheeling blend of reportage and invention, chronicling distant parts of the Mediterranean through maps, pictures, hearsay, poetry and facts. Like gossips buoyed up by one another, the isolarii were the companionable sort. One book would give way to a second when its authority ran dry: you’d be reading about Constantinople, and on mentioning Cyprus or Malta, the writer would point to a peer who’d covered that ground before.

For the last two years, I’ve been enamoured of isolarii, a subscription series of books coedited by India Ennenga and Sebastian Clark, a duo based in New York. It ‘revives’ the Venetian genre: these new isolarii, each volume declares, ‘form an archipelago of today’s most avant-garde figures and groups’. (The series is capitalised, but not the individual books.) There are six so far, of different lengths and types, from Russian feminist poetry to an investigation of salmon farms. Though they don’t explicitly cite each other, the ‘archipelago’ metaphor is meant to conjure a fuzzy link: just as the fauna shared by a chain of islands might change gradually across several coasts, so the isolarii share family resemblances.

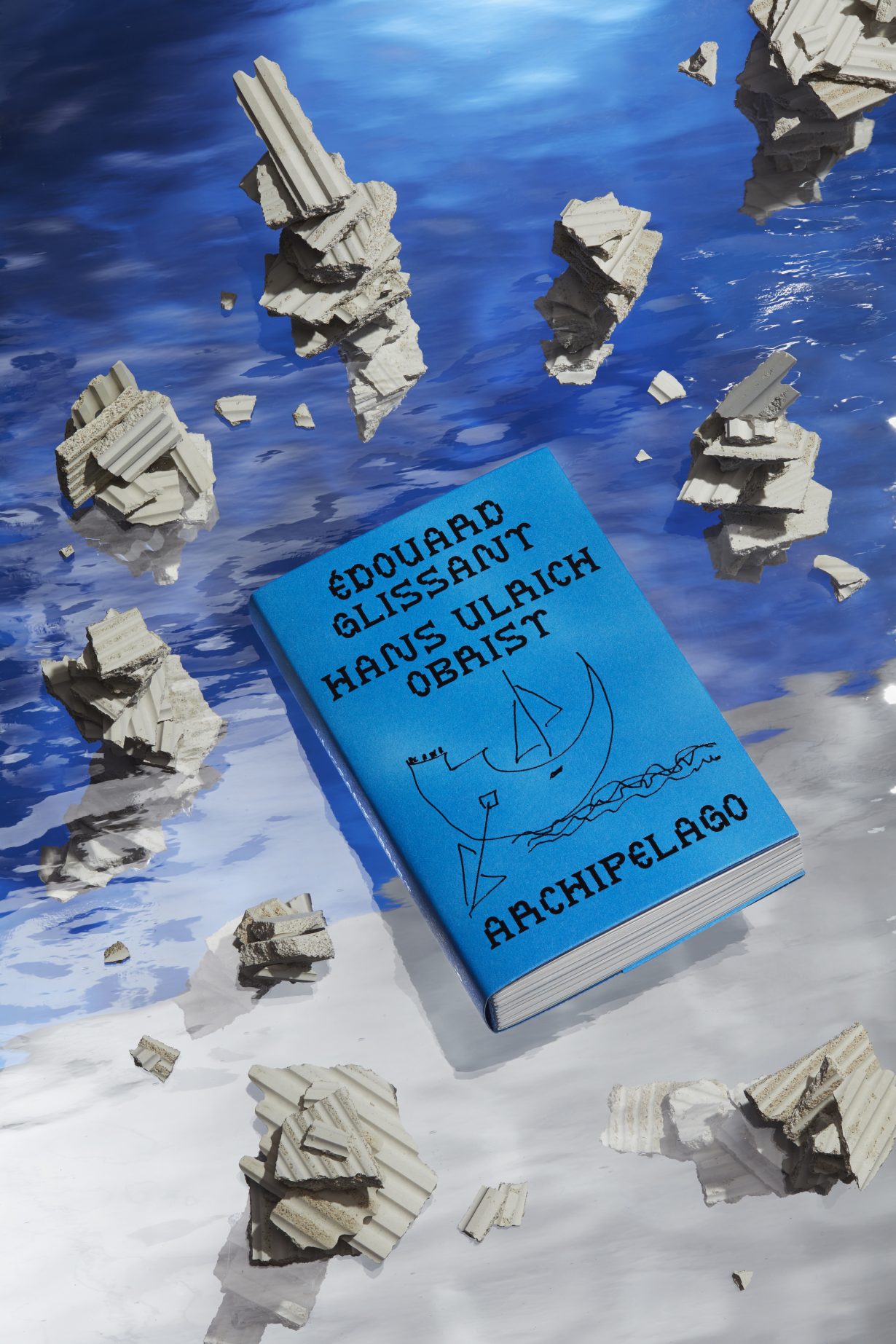

The appearance of the books intrigued me first: they’re identically sized, and small enough to sit in the palm of your hand. As with any kind of cuteness, this is a ploy. Ennenga and Clark had the idea for the series when the latter was reporting on the assembly lines of Foxconn, the electronics manufacturer; in an email, Ennenga tells me that their books mimic “the number of words per line, and the text-size, of an iPhone”. Archipelago, for instance, a series of dialogues between Hans Ulrich Obrist and Édouard Glissant (introduced by Trinh T. Minh-Ha), has 219 pages, but only 80 to 100 words on each. The editors wanted to play off the “tactile, repetitive iPhone gestures” that our hands perform all day. “We’re not Luddites,” Ennenga adds, “but we’re resistant to the automation of thought.”

Anyone who values thinking might make a similar claim – the process can never be wholly automatic – but the isolario mimics our devices’ size in order to swap their function out. The internet never stops gazing back at us, and addiction is the ruin of attention: you can put down your phone with ease, but it’s trickier to focus on what you take up in its stead. Since they’re books, your movement through an isolario is linear, a steady backdrop that the writer distends to weave your attentions into a tapestry. It’s an exercise for unlearning the mental mechanics of the endless scroll. Yevgenia Belorusets’s Modern Animal (2021), for instance, is about how people and beasts share an earth: it shuttles between stories, lectures and ‘transcripts’ (and yet, of what?), as well as photographs of birds. It seems to pick up the environmentalism of Salmon: A Red Herring (2020), a project report by Cooking Sections, then pass its dialogues onto Archipelago, in which Obrist and the late Glissant talk pensée archipélique. (By contrast, the weakest book is Street Cop, 2021, a dystopian graphic novel by Robert Coover and Art Spiegelman; there’s fun in its mix of gritty policier and futuristic milieu, but it’s too light a read, and has little to say to its stablemates.)

The purpose of the series isn’t strictly codified. As you read, you move between points, exploring and gathering; it’s experience as additive flux. In Archipelago Glissant emphasises that ‘creolisation’, his long-term prescription for social cohesion, is different to multicultural life: what he advocates isn’t ‘a state of identity’, but ‘a process that never stops’. On Ennenga’s phone, meanwhile, one note about isolarii is headed ‘systems for adventure’, as if ambition were itself a technology. Compare the smartphone to a mechanical siren, promising novelty but keeping you trapped. Stay on your island, your iPhone whispers; don’t go looking for something new.