“One of the goals of Russia is to eliminate Ukrainian culture,” says artist Pavlo Makov. “It’s a war between two civilisational processes.”

What happens to culture in times of war? How is it shaped within the shadow of conflict, and what does it, in turn, tell us? Ukraine’s galleries underwent a transformation as Russia’s military pushed ever deeper into the country. Artists and curators turned them into crisis centres and bomb shelters as the missiles rained down. But something else happened too, amidst the carnage: a concerted effort by art workers to protect the country’s cultural heritage. What has motivated people – in such a perilous situation – to snatch paintings from fires? And to return to cities under bombardment to salvage museum collections?

It’s a question I put to the organisers of the Ukraine pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale. On 24 February, curator Maria Lanko set off from Kyiv with the components of the pavilion’s installation Fountain of Exhaustion – consisting of 78 bronze-cast funnels – piled up on the backseat of her car. Lanko spent a gruelling week on the road, driving across backroads, finding shelter in freezing, abandoned houses along the way, before crossing the Romanian border. From there she passed through Budapest and Vienna eventually reaching Milan. “It was no especial drama,” she tells me in Venice, where she was joined recently by the pavilion’s other curators Lizaveta German and Borys Filonenko. “Easy compared to the people who stayed in the city’s bomb shelters.”

“It’s still very hard to talk about your closest people because so many more remain under inhuman conditions,” Lanko says. “So many artists – our community – most of them stayed and many of them volunteered. Our Zoom conversations are filled with lots of tears – but tears of love. We understand what is going on and what everybody feels at the moment.”

Fountain of Exhaustion’s artist himself, Pavlo Makov, had initially sought refuge in a bomb shelter in Kharkiv (incidentally, the shelter was formerly a contemporary art gallery, the Yermilov Centre). His forthcoming appearance at the Venice Biennale, unsurprisingly, was not at the forefront of his mind, he says. It was only after he helped his 92-year-old mother, wife and close friends flee the city as the bombing intensified – as they reached the western border, waiting for safe passage across – that he decided that he would also come to Venice. Being over 60 he was allowed to leave under the martial law enacted by President Zelensky, (being younger and male, Filonenko would have required special permission.)

“One of the goals of Russia is to eliminate Ukrainian culture. Culture – the visual arts, literature, music – is how we manage to live together, to answer our questions, to decide complicated questions for society,” Makov says. “It’s a war between two civilisational processes and between two cultures.”

The cultural barbarism that has accompanied Russia’s countless war crimes is not just collateral damage – the flattening of churches and theatres; the vandalism of school libraries; the burning of museums: these are acts of erasure and eradication. “For us being here in Venice to represent Ukraine – it is actually a matter of national security in a way. Which sounds weird, but not weird when a war is going on,” Lanko says.

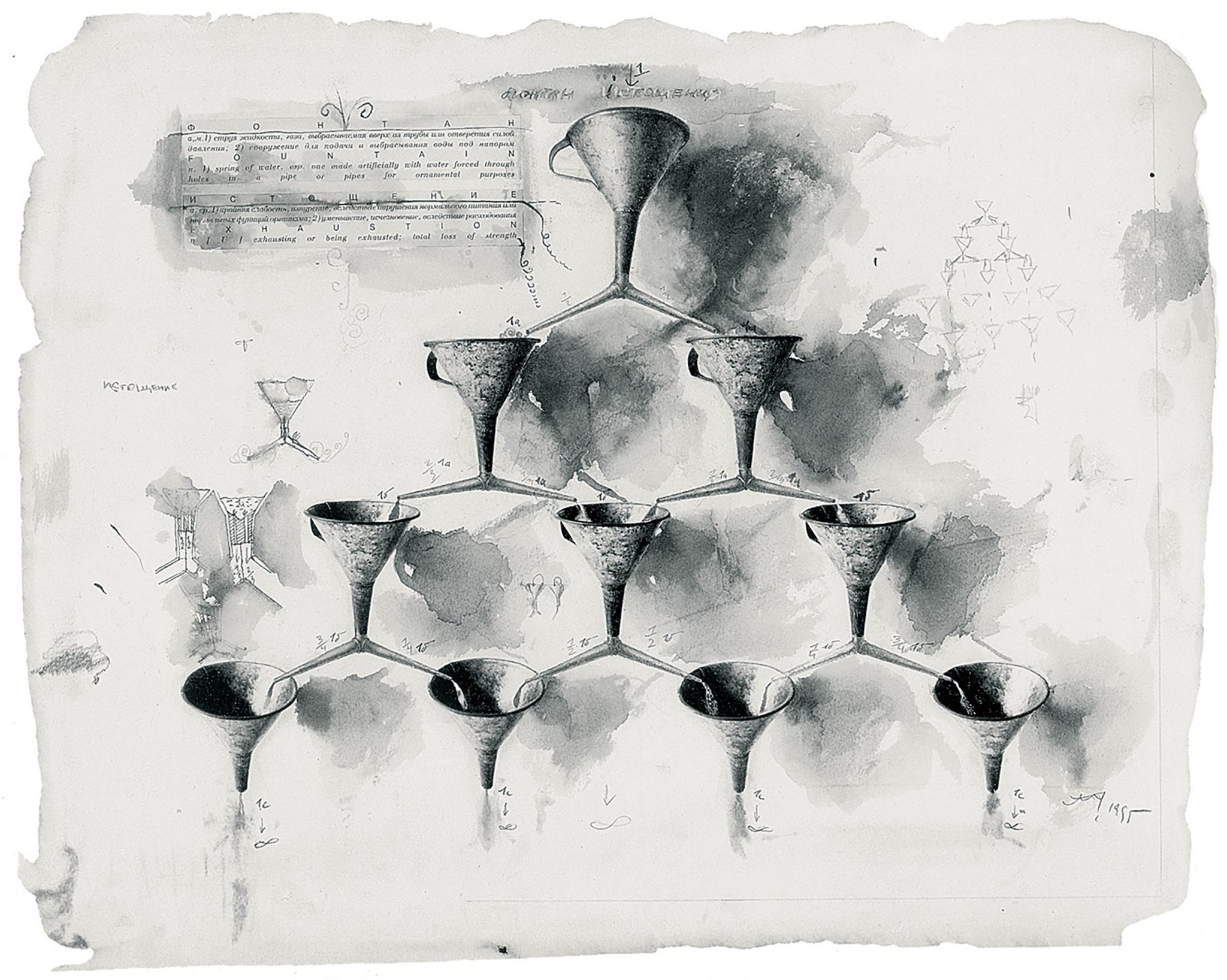

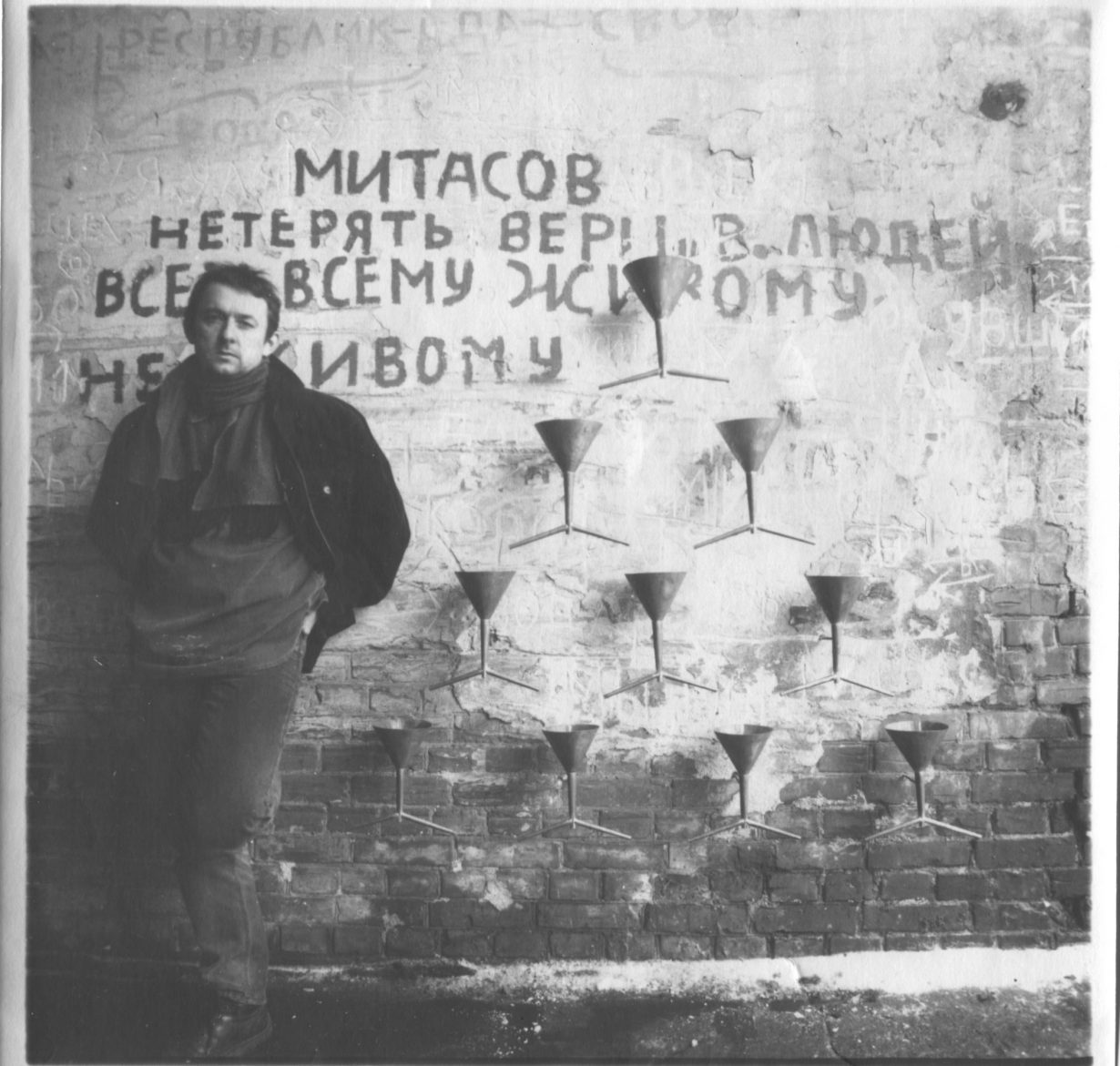

Lanko starts by showing me the basic element of Makov’s artwork: a green-bronze funnel that splits into two spouts at its bottom. Together the 78 funnels, arranged as a vast pyramid, form a fountain: water flows down the tiered pyramid, the liquid’s cascade gradually slowing to a drip. There’s a rhythmic process to it – the water trickling through, and then pumped back up: an experiment in tempo.

‘For a Ukrainian artist to be heard outside the country,’ the critic and curator Alisa Lozhkina recently wrote, ‘she must be adequate and predictable, obediently producing works on the themes that international curators and viewers expect from Ukraine – corruption of officials, life in a post-Soviet landscape, brutality of power, and now, of course, war.’ Of the latter, there’s plenty in Venice to go round. The Kyiv-based PinchukArtCentre is mounting a Venice exhibition of anti-war art; meanwhile the Ukrainian pavilion curators are working on another show within the Giardini, Piazza Ucraina, that deals face to face with the horrors of recent months. In that context, the Ukrainian pavilion offers something else, a crucial perspective that reaches further back in time.

Makov originally conceived the piece in 1995. He initially thought of it during a period when weeks of heavy rainfall flooded a wastewater treatment plant in Kharkiv; after the water supply became contaminated, officials blocked the city’s tap water. Makov wanted to give visual form to feelings of a city running on empty, its inhabitants powerless. “In those first years of independence, there was a lack of vitality in society, a lack of energy,” he explains. But the work’s significance has continually shifted – most recently, it can also be read as a waning of desire to protect democratic principles in Europe, its creator says. And while the fountain may be an allegory for today’s conflicts, it also speaks to our destabilised sense of time. “At the beginning when I was presenting this work, many people were upset about its title. Why exhaustion, they would say. Why not talk about a better future? These days, nobody ever questions the name,” Makov says.

The Biennale’s national pavilions – frequently the subject of furious debate over the contradictions and constrictions of dividing artists and exhibitions according to nationality – has found an unlikely defender this year. “A national presentation is not something that corresponds to how art functions in the world today. But for me, somehow, it has always been the most interesting part of the Biennale because those pavilions are blatantly political – you can see it right there, with the architecture of the pavilion itself, how the country wants to represent itself,” Lanko says. Meanwhile, the Russian pavilion – a mainstay at the Biennale since 1914 – lies empty this year. The pavilion’s two artists Alexandra Sukhareva and Kirill Savchenkov and Lithuanian curator Raimundas Malašauskas withdrew in February. The pavilion’s artists wrote: ‘there is no place for art when civilians are dying under the fire of missiles’.

Before the recent invasion, a sizeable portion of Ukrainian citizens – 15 percent – claimed to feel both Ukrainian and Russian. Even Makov is by his own admission ‘three-quarters Russian’ and was born in St Petersburg (then Leningrad). “All of us are political Ukrainians. We have a lot of Russian blood in our veins unfortunately!” Lanko quips. That feeling of related identity is becoming increasingly untenable (the contradiction in Russian military strategy of course being that it has been east and south Ukraine that has borne the brunt of the greatest devastation, the country’s Russian-speaking lands.) “So often we are asked: how come your closest relative, with a shared culture, attacked you? But we are not one culture,” Lanko says.

“I don’t feel so much of an artist these days, as I do a citizen – I am here representing not my exhibition but Ukraine,” Makov says. “Ukraine as an independent country is only 30 years old. I am 63. It’s a very young country and it is extremely important for a young country to state what kind of culture it has behind it. Many times in history, Ukrainian culture has suffered elimination on a physical level – artists, writers and musicians killed, works destroyed. We begin again and again the same stories.”