‘It has been very humbling to see and experience how the artists have worked around the pandemic’

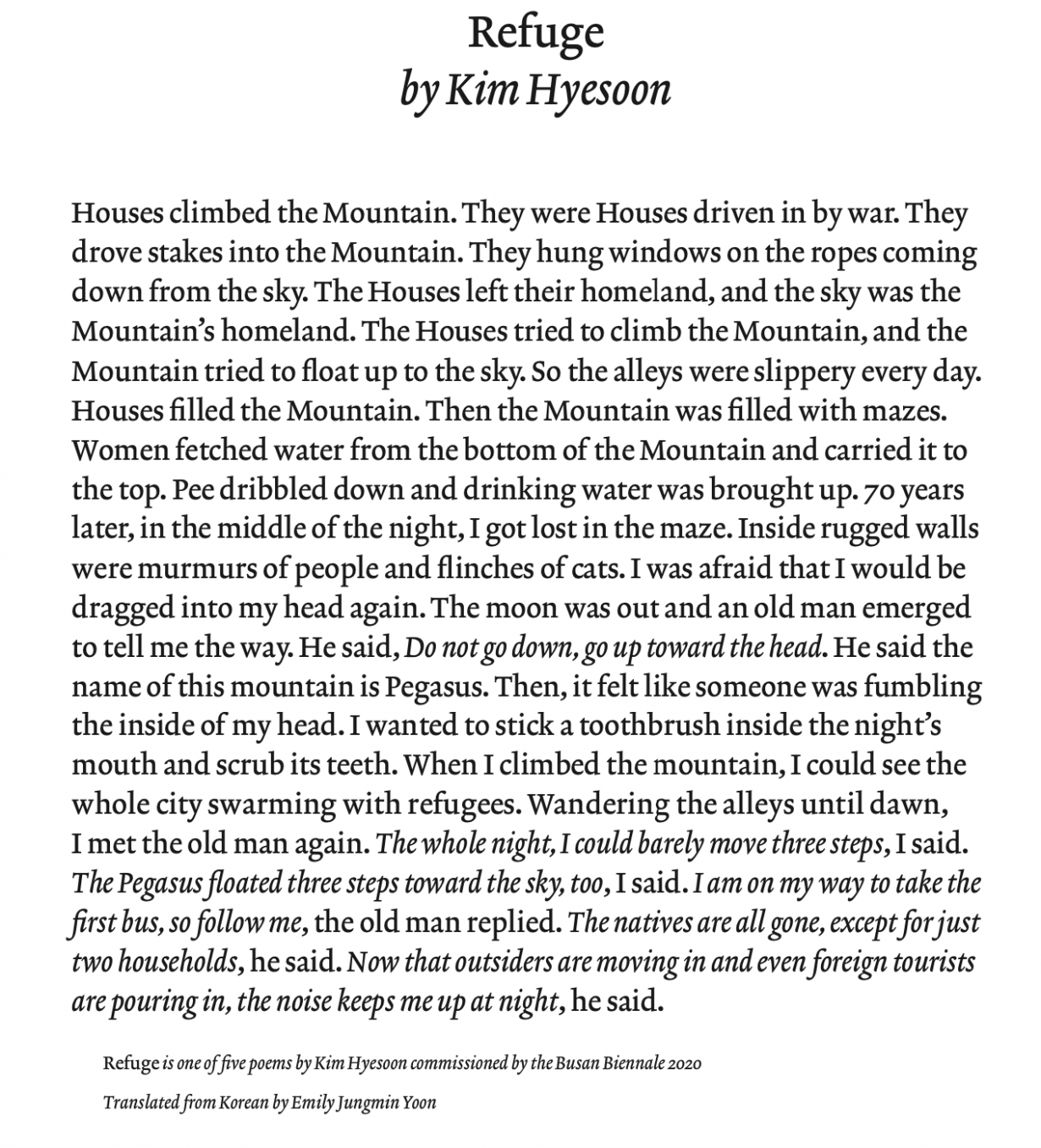

The Busan Biennale 2020, titled Words at an Exhibition: an exhibition in ten chapters and five poems, launches this September and is one of the few largescale art events in Asia that will take place this autumn. Directed by the Danish curator Jacob Fabricius (currently artistic director for Kunsthal Aarhus in his native land), who was appointed in July of last year, the exhibition takes as its generating concept the interpretation of works of art and their translation into another artform. Eight Korean and three fiction writers from Denmark, Columbia and USA, representing different generations, genres and ways of writing, were invited to visit Busan in late 2019 and then commissioned to write stories or poems ‘around or about’ the city. The stories structure the exhibition’s ‘chapters’ and the poems provide ‘intermezzos’. Each of the 67 participating artists and 11 musicians (from around the world) was asked to create a work in response to one of the texts.

‘This exhibition [which takes place at MOCA Busan and a number of spaces in the city’s Old Town as well as a warehouse in the Youngdo harbour] will also attempt to create multiple layers of fiction, and add numerous new filters, through literature, sound and art, to the city,’ Fabricius writes. ‘The audience will become detectives in the city… that’s how I imagine it.’ ArtReview Asia caught up with him during his two-week quarantine following his return to South Korea.

ArtReview Asia You placed an emphasis on words and story-telling for this edition of the biennial. Why is that, and, given that you are working in Korea, what place does translation hold within that?

Jacob Fabricius On a conceptual level the exhibition is inspired by the Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky’s most imaginative and frequently performed work, Pictures at an Exhibition (1874), a cycle of ten piano pieces describing paintings in sound. The poems that behave as ‘intermezzos’ recall Mussorgsky’s use of the ‘promenade’ in this work. Where Mussorgsky turned paintings into music, this exhibition will turn poems, short stories and urban space into a kaleidoscopic view made up of soundscapes and artworks. That’s a form of translation, or transmutation, as semioticians like Roman Jakobson (he coined the term) or Umberto Eco would put it.

The curatorial backbone is words, stories and poems written by 11 authors. Busan can in many ways be seen as a city of fiction – it’s the Korean capital of films like Train to Busan (2016), Ode to My Father (2014), among others – and hosts one of the largest annual film festivals in the region.

Why storytelling? Busan was one of the only cities that was not captured by North Korean troops during the Korean War, so given the content, place and local history I wanted to focus on stories that can be related to the city and South Korea. As a foreigner I feel I easily get lost in translation, lose track, or get lost in general because I don’t know the language, the signs, cultural codes and their differences. Storytelling is a different way of getting to know a place.

ARA Why is the fact that Busan was one of the few cities not captured by North Korea during the Korean War still relevant to a biennial today? It seems to me, with some of the editions of the Gwangju Biennale too, that history, or the past is used to frame the present to the extent that it can become something of a bind.

JF It can of course be a bind, but considering how present the DMZ and the division between North and South Korea is – through the uncertainties, conflicts and constant power-plays – I completely understand why the topic is often echoed in the biennales here. Koreans are constantly reminded of the situation, it is in their DNA, history and pride. Of course, I could have chosen writers who mostly just dealt with historical issues, but I selected a variety of writers and styles from different generations – some point towards the past, but most of the short stories deal with present, contemporary issues.

ARA Were there things about the contemporary city that inspired you?

JF The harbour is amazing. It’s huge. It’s rough. It has a certain smell. I love the machines, the rusty ships, the thick ropes and steel chains.

All along the waterfront you’ll find evidence that land has been reclaimed and developed. From the first Japanese settlements during the 1890s and throughout the twentieth century, the harbour has been the key to Busan’s growth and its strategic placement in relation to international trade. Busan is a large city that is squeezed in between the ocean and the mountains and eats its way into the landscape similarly to Los Angeles. Busan constantly grows and redevelops itself.

ARA On a more general level, what do you think is the purpose of the biennial? Is it to bring attention to Busan?

JF It was initiated in 1981 as the Busan Youth Biennale, by local artists who wanted to create an energetic scene. The merging of the Sea Art Festival and the Busan Outdoor Sculpture Symposium in the early 2000s forged what has become the Busan Biennale as it is today. It’s distinct from other biennales in having been initiated with the spontaneous participation and commitment of local artists. But I guess all biennales want to be in contact with the world, to bring attention to and showcase the scene and the city.

ARA Mussorgsky set out to achieve a kind of unique ‘Russian identity’ with his music, or at least an identity that existed outside the Western canon and drew on ostensibly ‘Russian’ themes. How do you fit these kinds of ‘local’ accents into your exhibition, particularly as a foreigner in Korea? Does your edition continue to interact with the local art scene?

JF I think it does. There are local artists on the board and there is a strong interest in the local scene. I have included local writer Kim Un-su, musicians Say Sue Me, Kim Ildu, J-Tong and Jinjah, and about five local artists in the exhibition. I have also selected some of the small Totatoga artist-run spaces as venues in the Old Town. The audience will get a glimpse of the scene and environment here. The warehouse

in the Yeongdo harbour, for example, is very interesting because it shows the raw side of Busan and not the touristy beach side of the city.

It’s true that Mussorgsky was inspired by and wanted to portray the Russian folk spirit. The ‘local’ accents have come quite natural to me, because I have worked with quite a few Korean artists before. But my new discoveries and the presence of ‘local’ accents are more evident within the selection of writers and musicians. And I must admit that I had not seen the works of Nho Wonhee and Suh Yongsun before: they belong to an older generation of political painters, and I was astonished by their works.

ARA How did you choose the writers for this project?

JF Originally, I thought it was impossible to commission new texts within such a short time – and wanted to build the curatorial frame on existing novels and stories. After a while I realised that it was much more interesting to invite writers, give them a short deadline, have them visit Busan and write their stories. This all happened during October and December 2019.

Last summer I was researching and reading quite a few young Korean writers. Luckily the Literary Translation Institute of Korea support a lot of young Korean writers by getting their stories translated and promoted. I have mainly invited South Korean authors because the country has a complex history and I was interested in finding writers who could dive into the language, locations and history on as many levels and different genres as possible. Given the short timeframe I thought having too many foreign writers would be difficult… that they would get lost before they had begun and time didn’t allow for that. But I also wanted foreign writers who could get lost in translation.

In fact, Mark von Schlegell wrote a story about a writer getting lost, and in a different sense, Andrés Felipe Solano’s detective gets lost in his ‘self’. Andrés is Columbian but lives here with his partner, so he has an interesting double perspective of things in Korea. Amalie Smith works as a visual artist and has also published several books, and I have worked with her once before. I like the fact that she occupies a double role – a few of the artists in this biennale have worked in different fields, like Hannah Black, Gerry Bibby and Kim Gordon.

ARA And has this form of mediation proved even more useful in and out of lockdowns?

JF The lockdowns have been a nightmare on many levels, but the conceptual skeleton was there and luckily the stories were already finished before March 2020. It has not been easy for many artists to produce and do research. But many have developed new ways of researching, finding material and producing work. It has been very humbling to see and experience how the artists have worked around the pandemic.

I had just spent 10 to 14 days in Korea between February and March, and arrived back in Denmark five days before Denmark closed its borders on the 14 March. If I hadn’t been there during those weeks, it would have been very difficult to select spaces, locations and so on. During the lockdown I would Skype with the exhibition team leader, Seolhui Lee, for up to five hours daily.

ARA You said ‘many artists have developed news ways of researching, finding material and producing work.’ Could you give some examples of that?

JF Generally speaking, the artists have in several cases had to rely on the help from the exhibition team in Busan. They sent instructions and asked the team to use their hands, eyes and ears in relation to collecting, recording or researching for their new works. The exhibition team have been activated in ways that could not have been imagined had artists been able travel to Busan themselves.

Kim Gordon, for example, sent short descriptions and instructions like: ‘Some back alley, if possible the back of a restaurant or an alley where there are noodle shops in the old part of the city. A young man/boy and girl wearing denim jackets looking at each other and then they kiss. Also a cigarette stuck in the boys mouth without lighting it and then giving it to the girl. The boy riding on a bus. A woman eating a donut with long legs. An old woman eating noodles. A boy sleeping. Walking thru the big shopping complex shooting the shops etc that could be longer like 10 min […]’. This was to be filmed with a smartphone in Busan. JiYeon Seong (from the curatorial team) then asked friends to participate, found the places and settings, and filmed it with her phone before sending the raw footage to Gordon, who then edited them with her own clips and made a soundscape. It turned out to be an amazing hallucinogenic film.

Francesc Ruiz asked the team to find LGBT+ logos in Busan, and to do research on queer festivals, protests and related issues around the city. From this research Ruiz has created a storefront zine shop with his own comics, posters and stickers in the Old Town area. Gerry Bibby asked a Korean friend to be his ‘spy’ in Busan and do several readings and performances with him in public spaces, also relating to LGBT+ people and locations in Busan. Gerry asked Pooluna Chung from our team to measure weird architectural details at MOCA Busan for his concrete poem sculptures. Robert Zhao Renhui was looking for wildlife

in urban spaces, so he asked Jihyun Woo from the team to reach and find locations in the harbour – together they selected and placed four surveillance cameras in a small abandoned house and filmed the space for weeks. The recordings were sent to Robert, who then edited and made an installation at the warehouse venue in the harbour.

Lasse Krogh Møller’s instruction was: ‘Pretend, if you can, that you have never set foot in Busan before. Look at the streets, the shops, the buildings, the people there. What do you see? Pay notice to the small, diminutive things or phenomenons in the street. Look for signs of human activity. Also diminutive traces and leftovers. Collect or register some of these things. Either bring them with you, or take a photograph of them, and/or describe them with words. Please note the location; address, name of supermarket etc. Ask someone on the street, or in a shop, if they will be so kind and draw you a map, that gives you direction to another spot, of your own choice in Busan. It can be far away or it can be nearby; as you like. (Pretend that you don’t have a phone with a map, if needed. Or something else).’

Other artists like Louise Hervé and Clovis Maillet, Zai Tang and Rei Hayama, Mercedes Azpillicueta, Dave Hullfish Bailey, and Inger Wold Lund created their own ways to do site-specific pieces and collaborations without having ever been to Busan. While Angelica Mesiti and Nicolas Boone, both living in Paris, and Sara Deraedt, Jean Katambayi Mukendi, Stephan Dillemuth, and others, found their own ways of generating material and producing new works that related to the stories they chose. All in all, there are many really exciting approaches I think. I have not mentioned any of the Korean artists because they could easily come to Busan and do research and make site-specific works and installations.

ARA When you talked about Busan earlier, you referenced film (Train to Busan, etc), and the curatorial conceit derives from music and fiction: to what extent is the biennial a meditation on mediation and its effects? Particularly given the increasingly mediated lives people have had to experience during lockdowns. And to what extent have you had to rethink the idea of the biennial as a social gathering?

JF This year we have had to rethink everything we do, how we work, how we travel and transport work, not just me of course nor the biennale – everybody has been influenced and affected. Generally speaking, it took a longer time to settle on particular artworks, and during the lockdown some artists have changed their contribution completely. People have reacted very differently to the lockdown and their suddenly exhibition-free calendars.

Right now, South Korea is experiencing a second wave of COVID-19, so now we are discussing how we can host an alternative opening and distanced press meeting and so on. During the lockdowns we reached out and did three open calls to Busan citizens. We did it to engage people in the biennale and asked people for their scent and sound memories, to involve them in the process and creation. We got 842 people to participate in the open calls.

ARA Has the limited potential for international travel (in terms of visitors coming to see the show from outside of South Korea) changed your idea of the audience you are serving?

JF There will be very few international visitors – two weeks’ quarantine in a government appointed hotel with daily (cold) meals at 8am, noon and 6pm will scare most travellers away (trust me, I know). Actually, it has not changed my idea at all – when COVID-19 hit us in the spring, I had already finished my artist list, which included many Korean artists, writers and musicians.

Usually there are around 300,000 visitors to the Busan Biennale, and if 5% are international visitors, we lose 15,000 visitors. It is a real shame and I would have loved to share this with artists, colleagues and friends… but unfortunately this will not happen. The only non-Korean artist who has chosen to do the quarantine is Bianca Bondi.

ARA Do you think this a change that large art events will now have to calculate for? (Environmental concerns come into play here too.) And does it perhaps provide an impulse for a recalibration of the very idea of a ‘global’ artworld?

JF I think people will choose their travel more carefully and not zip from art fair to art fair or biennial to biennial – I know I will. It may come back, but it will take some time.

The Busan Biennale 2020 is on through 8 November