This first international retrospective asks for Mesmaeker’s status and influence as a media artist to be reconsidered

The first retrospective for Jacqueline Mesmaeker (1929–2023) outside her native Belgium begins with multiple works related to Lewis Carroll that point directly to her main interest: sketching out, sometimes literally, additional doors, levels and possibilities in existing artistic, literary or historical sources. In the ten-metre-long Les Porte Roses (1975), a phrase from Alice in Wonderland (1865) alluding to the storyline’s variously sized locked doors is written progressively across the gallery wall, a few words at a time, on 32 sheets of paper that also feature gradually growing pink rectangles, like Carrollian portals themselves. In the series of pale purple drawings Lapin (when suddenly a White Rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her) (1974), which follow a typed-out page of Carroll’s text, a pointillist rabbit progressively loses its dots and disappears.

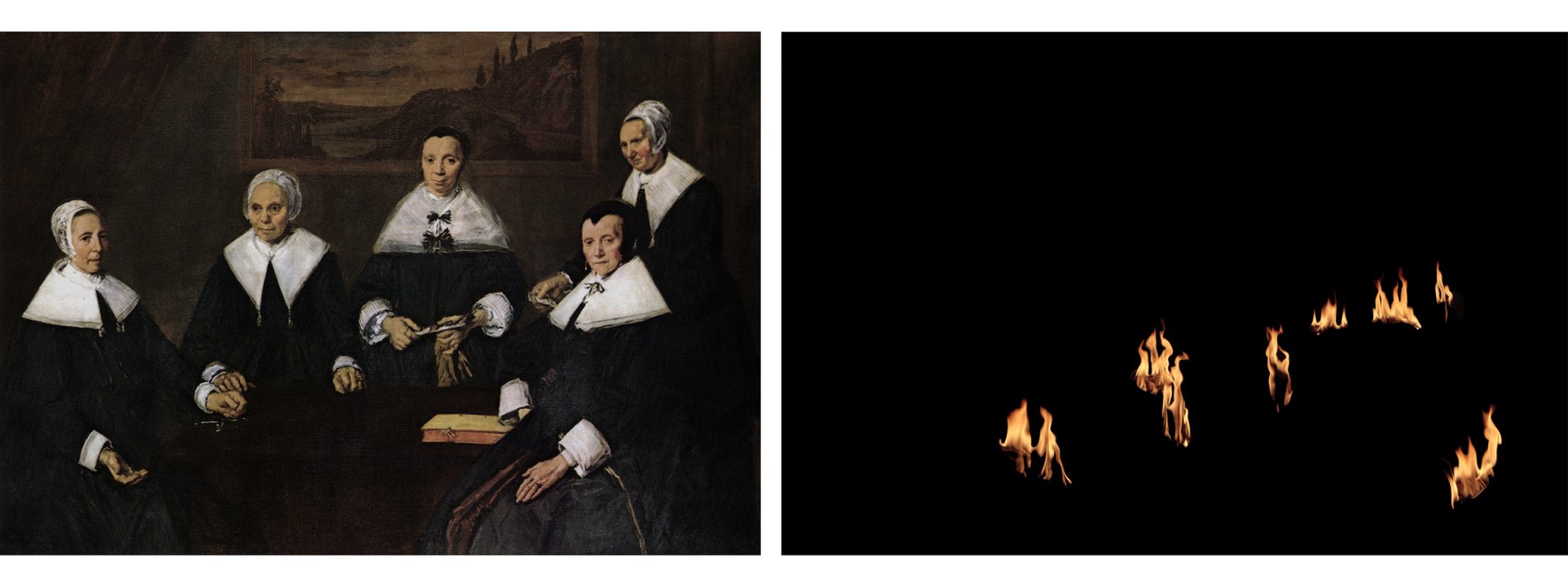

The artist, whose credo was to spotlight the overlooked, avoids merely commenting on existing artefacts; rather, she uses them as jumping-off points, then brings her work and sources into comparative juxtaposition. The double slide projection Les Régentes (Franz Hals / Paul Claudel) (1990–2012) deploys a detail from Frans Hals’s group portrait The Regentesses of the Old Men’s Almshouse (c. 1664). In Mesmaeker’s digital image, alongside a reproduction of the painting, only the sitters’ hands are shown in their original, rendered as flames in a way that changes one’s perception of what matters in the painting itself.

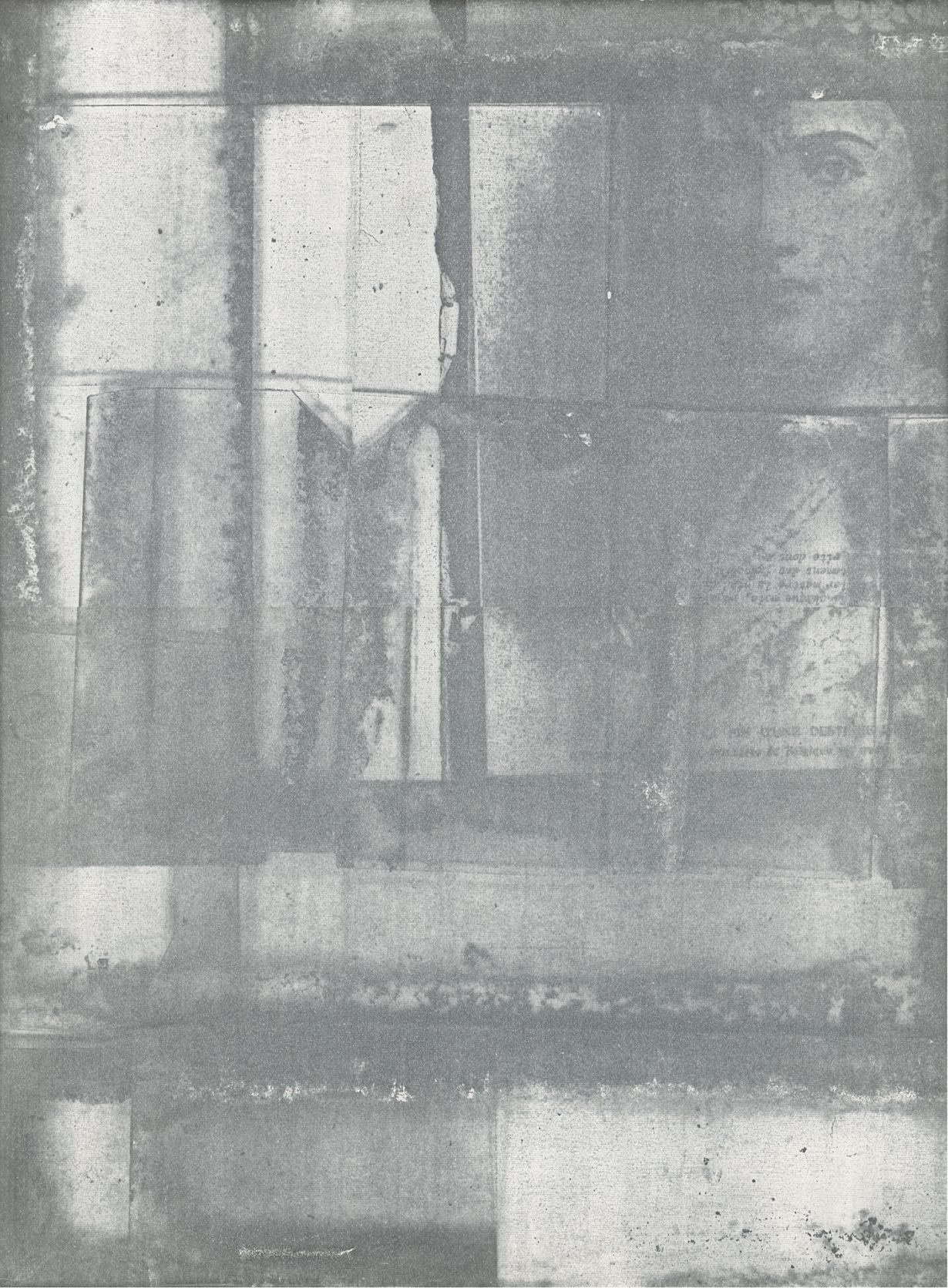

Les Charlottes II (1977) and La Serre de Maximilien et de Charlotte (1977–2020) address the fate of Charlotte of Belgium. After a short reign, 1864–67, as empress of Mexico and the subsequent expulsion and execution of her husband, Maximilian of Austria, Charlotte was locked away for 50 years in Bouchout Castle in Meise, Belgium, believing herself still to be empress. Les Charlottes II consists of Charlotte-referencing images and documents, which were covered with greenhouse glass while being copied, rendered as faded, semitransparent black-and-white duplicates, suggesting an appropriately hazy relationship to truth. La Serre de Maximilien et de Charlotte, meanwhile, is a fragile bamboo greenhouse structure that, we’re told, references Maximilian’s botanical interests, the decline of greenhouse culture originally widespread in the region where Charlotte was kept, and, seemingly, the possibilities and conditions for the representation of memory and forgetting in general.

Elsewhere are a multitude of graphic, painterly and sculptural works hovering between the experiences of seeing and reading: visual and notational additions affect the perception, and readability, of eight books by, among others, Virginia Woolf, Lenin and Peter Handke. Yet the section focusing on films deserves particular attention: 1998 (1995), filmed inside a lift in a cooling facility and recording the light peeking between its doors as it moves, nods wryly to the ‘zips’ of Barnett Newman, one of Mesmaeker’s favourite artists. And Surface de Réparation (1979), a deconstruction of football and of filmic montage, in particular asks for Mesmaeker’s status and influence as a media artist to be reconsidered. Using four projectors on 12 suspended translucent silk tulle screens, arranged in layers and viewed from one end, the work intermingles daylit images of two of Mesmaeker’s friends miming kicking footballs with others showing the movement of footballs recorded at night (and rendered as moonlike white circles, or a ball of lightning moving between the screens). Players and balls coincide only by chance, the viewer imagining a relationship between them, while filmic representation itself is taken apart and reassembled. As Mesmaeker is posthumously reevaluated, this might be a key point of reference in classifying her work less as mythically enigmatic – as it’s been thought to be before – and more as analysing the endless possibilities for new narratives or emphases to be spun out of preexisting media.

Secret Outlines at Museum der Moderne, Salzburg, through 14 September

From the Summer 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.