Jane Jin Kaisen’s Halmang tells the story of the women sea divers of Jeju Island

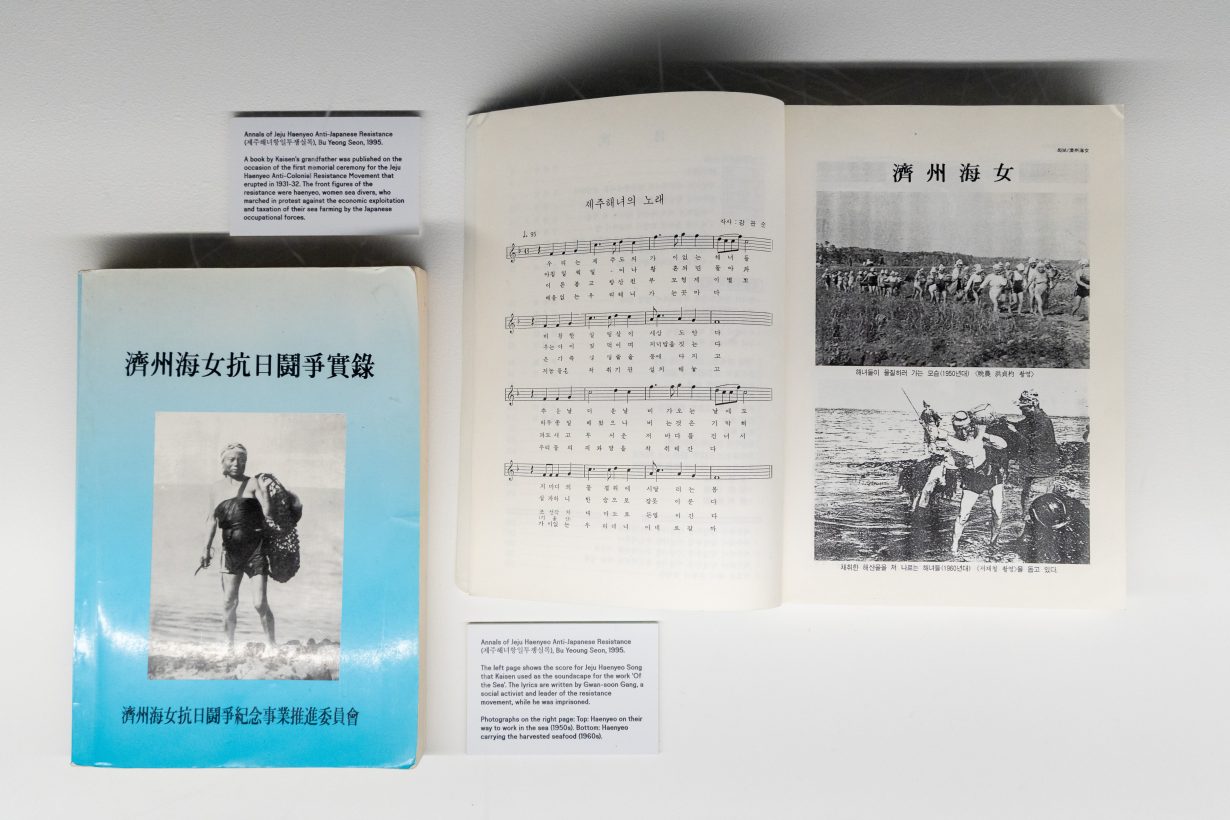

I’m surveying a rugged coastline in fine spring weather, my gaze following artist Jane Jin Kaisen’s retreating figure as she heads towards the sea. So quietly immersive is the video Of the Sea (2013) that you feel disinclined to stand still. The artist, clad all in black and wearing low-heeled ankle boots, is stepping determinedly over a rocky shore, a net containing rudimentary diving equipment slung over her shoulder, her hair in a ponytail. Kaisen stops momentarily to pick a book up off the ground – it’s Annals of the Jeju Haenyeo’s Anti-Japanese Resistance, written by her grandfather in 1995.

In the background, a female voice is singing an old Japanese melody: ‘We are the Jeju haenyeos of Jeju Island forever’, sings the voice in Jejuan, relayed to the viewer via subtitles in English. ‘The world knows how wretched we are. Rain or shine, cold or hot. Leave early and come back at dusk.’ Jejuan activist Kang Kwan-soon composed the lyrics and put them to the Japanese melody while she was imprisoned, having been incarcerated for two years and six months for being the main person behind the anti-colonial movement. Though banned throughout Japanese rule of Jeju Island in Korea up until 1945, the song was sung by haenyeo sea divers. Still walking with grim persistence, Kaisen is nearing the sea. Will she stoop to the ground and dive headlong into the waters?… The video abruptly comes to an end. The credits roll. Exhibition continues.

Jeju Island lies south of the Korean Peninsula. Mount Hallasan, a dormant volcano, towers above it. Jeju got its form through aeons of volcanic activity: on its outskirts is a natural wall of black basalt, once carried to the shores of the island on streams of fiery Holocene lava. In Halmang (2023), elderly Jeju women wear bright colours and patterns, and are engrossed in communal activity: they are sitting on the coastline, meticulously folding a continuous length of sochang, a light and seemingly endless white cotton cloth, against which the wall of craggy rock appears as an almost animate, bestial force. The women go about this without speaking, their movements calm and purposeful. They are a community, working together towards a purpose which isn’t clear to the viewer. Behind them, the sea’s waves angrily break and swell, just as they always have done. Despite the intense roaring of the sea filling the gallery space, it is the women’s collective silence that fixes you to the spot.

The women of Halmang (the work’s title is the Jejuan word for goddess, also for grandmother) would have been infants during the Jeju Uprising which was suppressed in a series of massacres from 1947 to 1954, two years after Japanese colonial rule in Korea concluded with the end of the Second World War. These massacres, by the United States Army Military Government in Korea and then the government of South Korea, involved the killing of many Jejuan villagers; tens of thousands of people were accused of being communist sympathisers, forced to flee, imprisoned in internment camps – including Kaisen’s grandfather. Sixty years would pass before the government of South Korea apologised for its role in the massacre: in the intervening period, it was illegal to mention the suppression of the uprising or even the uprising itself.

What could these women who survived these massacres do during the period of enforced silence? To make a living, they did what their ancestors had done for centuries: they worked as sea divers, harvesting seafood from the shores of Jeju: abalone (shellfish), seaweed, sea urchins and squid in hauls that would need to feed entire families. ‘The earliest people to speak of the massacres were the second generation of children of victims and survivors,’ Kaisen explained to me. ‘This was mainly through writing – for example, the work of Hyung Ki Young – and through theatre.’ The shamans of Jeju, as well as enacting seasonal rituals for the sea goddess every spring, would pass down myths through performances. Mothers taught their daughters to be haenyeo; shamans pass down the female line. Kaisen’s inspiration in these works is the memory culture of Jeju, which is increasingly threatened by modernisation and the changes brought about by mass tourism to the island. ‘Things that were silenced in public discourse could be addressed in the semi-public framework of ritual mourning,’ Kaisen explains. The sochang cloth has a spiritual function as a symbol of the cycle of life and death. Kaisen’s work asks how to preserve the spiritual practice of Jeju in a way that is sensitive and that maintains the social cohesion of the centuries, while the nature of work itself changes with modernisation – traditional methods of harvesting seafood have been replaced by industrial methods, for example, and mass tourism has changed how traditional customs are preserved.

Individuals living comfortable, sheltered lives have historically commissioned and enjoyed art that romanticised the lives of people in the fishing trade. In 1863, the French composer Georges Bizet presented to the Parisian public The Pearl Fishers: an opera about fishermen in ancient Ceylon (Sri Lanka). Neither Bizet nor the librettists had travelled outside of Europe: they knew little of Sri Lankan worldviews and understood much less about the lived experiences of the country’s pearl fishers. Or take esea contemporary itself, which is located next to Manchester’s former fish market. The Victorian facade of the red-brick market building has friezes depicting fishing life: stoic men, longsuffering women. These are the kinds of images that art can and should refuse, and instead seek the truth from the people whose lives are most impacted. The very real danger of cultural erosion is that the wealth of human experiences, from the daily grind to the horrors of atrocities, can be diluted, masked and ultimately erased: art is manifestly the most powerful way of mediating memory, where mainstream narratives neglect to do so.

Frances Forbes-Carbines is a writer with pieces in publications including The London Magazine, Antigone Journal and UnHerd