In Observations: Rose, the artists demonstrate how an artwork can be deeply political without being didactic

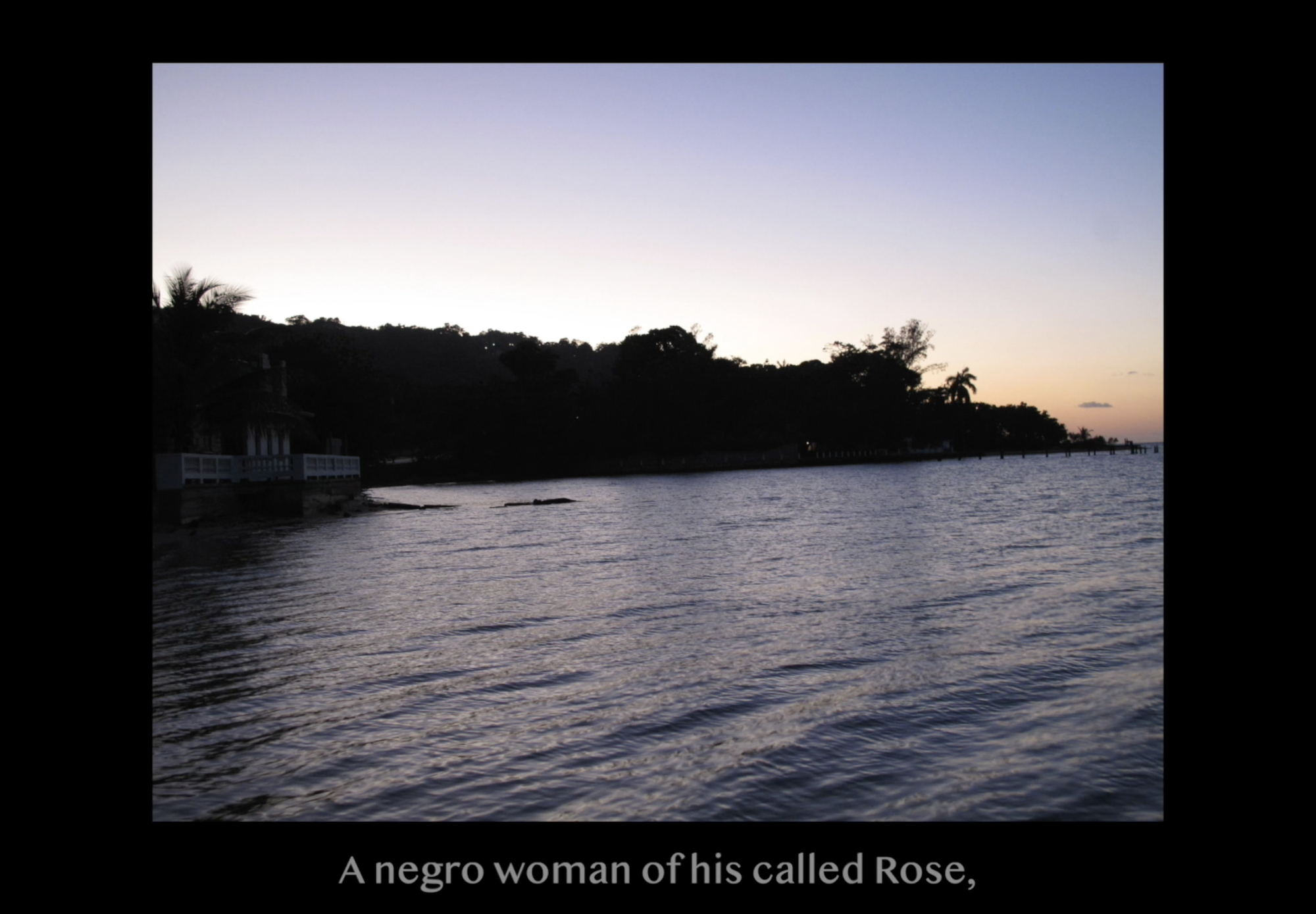

In Britain, it’s stereotypically assumed that the weather is an innocuous topic, free of controversy. Yet, depending on one’s circumstances, within its conviviality are less-than-comfortable thoughts and memories. Joy Gregory and composer Philip Miller’s 2021 video Observations: Rose is a slideshow mostly consisting of photographs of Jamaica’s luscious vegetation and the Caribbean Sea, in different states of roughness and calm, with Gregory’s close angle and appreciation of the island’s temporal variances – beyond the touristic turquoise – emoting familiarity and affection. Grating against these sentiments is a horrific anecdote, narrated via subtitles, linked to the former British colony’s slaveholding history. And over these visual and textual components, we hear phone interviews that Gregory has conducted with other Jamaicans, asking them about their experiences of migrating to England or, in some cases, moving back. During one call, Gregory explains that her questions are “about… the weather, really”. The way she says it, with that pregnant pause, implies already that the weather encompasses much more than rain or shine.

In her interlocutors’ words, the smog and cold of 1950s London turn out to be inseparable from the loneliness and longing, intensified by memories of the warmth of Jamaica – while the blissful contentment of the interviewees who live there now substantiates these memories, as do the beautiful images. Adding to the work’s emotional complexity is Miller’s cello soundtrack, made up of achingly drawn-out chords – I picture one of the instrument’s strings threading errantly through time – which seems to pick up on wounded depths veiled in the candid reminiscing to which it acts as a musical backdrop.

Over the past 40 years or so, Gregory’s go-to mediums have been photography and film, but in this work much of the emotion comes from her presence as a listener – her receptivity as a photographer reemerging in conversation. “So if you close your eyes and think about Jamaica, what do you see?” she asks one woman gently. What’s moving about the answers is partly the way the verbal content (“the green grass, the clear sky, the mountains”) rhymes with the sensitivity of Gregory’s lens to the way light and colour convey morning coolness or the warmth of seawater. But most of all it’s in the general feeling of candour, which at times can be traced in the technical glitches (Gregory: “My phone’s so quiet…”), although it manifests mostly in vocal intricacies – the vulnerable abandon of speaking about something yearned-for, the stop-start of getting the memory right, the daydream pauses. On the few occasions when the words are muffled, this serves to emphasise the release of feelings – gratitude, joy, sadness, anger – made possible by the trust between speaker and listener, something implicit yet tangible. Empathy here is less based on cognitive understanding than the rawness of speaking and listening, while there may also be something therapeutic, for Gregory’s interviewees, in the mental reorientation she encourages.

Gregory’s affordance of a sense of self to the people she’s speaking to is in stark contrast to the violence of the subtitles, which form the 15-minute video’s only linear narrative, a storyline that is at odds with the more haphazard, freer and multiple conversations in the voiceover, looped on a separate, hour-long track that exceeds the duration of one viewing. Told in the third person, the story follows an unnamed man’s medical treatment of a ‘negro woman of his called Rose’ who suffers from ‘melancholy’. It’s an unnerving, ugly, dissonant account, especially when he scarifies Rose’s neck, or when we read that white pustules form on her body, caused, perhaps, by the drugs and other treatments he is forcing on her. Just as disquieting is the distant, monological tone, heightened by the text’s slow delivery, often just three words at a time, like administered medicine or some kind of slow torture: she is ‘hard, as all mad people are, to work on’. This contrasts with the voiceover, whose freewheeling and dialogical generosity relinquishes much of the artist’s authorial control.

The mind’s juggling of voice, text and image and its disparate readings of the beautiful Jamaican landscape is suggestive of multiple realities intertwining (perhaps it’s more than one string I see in Miller’s score). At the end of the sequence, with about three minutes to go, the format of the photographs switches from rectangular to square, the colours faded. The Jamaican overgrowth is replaced by a more trimmed-back beauty, featuring neoclassical follies, a huge, white-ribbed greenhouse and swans – for now we are in London’s Kew Gardens, and by the time I clock this the images have jolted to another new format, in high definition and stretching the full width of the screen. The square images are like postcards, England seen from afar and long ago, whereas the widescreen envelops us, the progression reflecting the journeys of people and flora from colony to metropole. The beauty of Jamaica can be joyful and sad at once, a duality reflected at Kew, a colonial edifice where many of the plants that Gregory and her interlocutors remember so fondly can be seen. Although he is – pointedly – unnamed in the work, Gregory tells me that Rose’s abuser is based on the seventeenth-century collector of plants Hans Sloane, and that Miller’s score adapts an Angolan slave song noted down by a freed Jamaican slave and musician named Baptiste.

Gregory and Miller’s great achievement in Observations: Rose is its registering of how history, memory and everyday experience inflect each other in varying, inexact ways and degrees, demonstrating how an artwork can be deeply political without being didactic. By not naming Sloane or giving the date or location of the subtitled narrative, and by not revealing the root of the background music, Gregory and Miller detach them from their historical specificity and leave open the extent to which they pervade the images of present-day Jamaica and Kew – and yet they do, in some ways, pervade them, as does the heartwarming voiceover. The sentiments carried in the text and the sound contaminate each other too, as the artists daringly juxtapose two kinds of care, the oppressive and the loving. The weather, something changeable and diffuse, always affecting your mood in ways you can’t put your finger on, is an apt metaphor for the indeterminate relationships between past and present, time and place.

Observations: Rose will be on show as part of Joy Gregory: Catching Flies with Honey, at Whitechapel Gallery, London, 8 October – 1 March

From the October 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.

Read next: How Donald Rodney found refuge for the Black body in an exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery