Neïl Beloufa’s prophetic satire about a hallucination-inducing pandemic (and the elites in charge); Heather Phillipson memorialises our cultural exhaustion; and Rehana Zaman on feminism and solidarity

It’s been much discussed in recent months that as art venues have temporarily closed, galleries and artists have moved the presentation of work online, and that has meant an unprecedented (and often fantastic) offering of great video to watch. It’s worth adding to this that much of the work currently on show is – by necessity – older than the pandemic, having been made in the years and months before lockdowns, distancing and economies seizing up. Catching up with video that you’d not had the chance to discover before (where was I all those years? Well, clearly not everywhere) is now often fringed with a slight melancholy for times BC (before COVID-19).

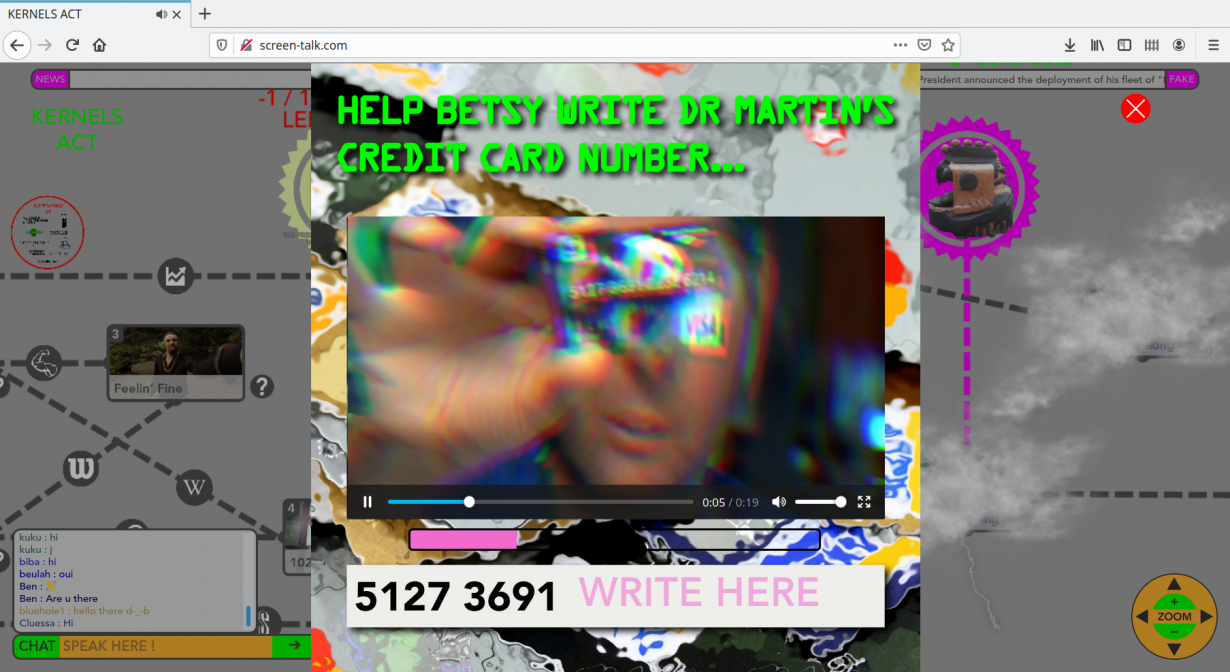

On occasion, video art from the recent past can seem downright prophetic. Neïl Beloufa’s Screen Talk was originally conceived as a ‘mini-series’ of short videos in 2014. A clownish satire about a global, hallucination-inducing viral pandemic, it follows the fortunes of a hapless, self-serving bunch of cosmopolitan types, including a pompously incompetent virologist, his haughty collaborator, his wife, her mother, and assorted statisticians and epidemiologists, all pontificating about their mission to save the world, while uttering gibberish equations about ‘sixty percent chances that our people won’t be ninety-nine percent OK’. Beloufa’s videos, however, have been newly recast as an interactive website www.screen-talk.com, in which you, the locked-down viewer, get to navigate a glitchy, infographic story-path, while having to pass increasingly idiotic meme-like puzzle-challenges (how do you spell ‘Schwarzenegger’?) to move on to the next episode. The videos are all prefaced with an apologetic caveat that ‘the satire and situations of Screen Talk were conceived and filmed before the discovery and spread of COVID-19’, but if anything, Screen Talk’s bleak comedy is really of the distracted, self-obsessed members of a social elite who are inevitably in charge.

If Screen Talk is gloomy about the venality of current global society, there’s a positively apocalyptic quality to Heather Phillipson’s TRUE TO SIZE (2016), currently being showcased on the New Museum’s website. This intense, two-minute image-with-monologue careens through a world where the animal and organic realities of human experience and desire tangle violently with digital capitalism and the arid aesthetics of commoditised sex and designer individualism. It’s in fact the first part (titled Afterlife) of seven, all of which can been found on Phillipson’s own Vimeo channel, which unfurl the panic of millennial experience, scathing in its rejection of a conformist culture of femininity and the social control of sexuality. Against a backdrop of ecological crisis and world’s-end-ism, Phillipson’s series memorialises the sense of cultural exhaustion which, in retrospect, was kind of waiting for the social crisis of the pandemic to happen.

If Beloufa’s and Phillipson’s works intimate a moment of crisis pregnant with the possibility of change, but steeped in a late-capitalist aesthetic of catastrophe, an antidote might be found in the generous and optimistic lens of Rehana Zaman’s Lourdes (2018), online as part of Camden Art Centre’s ‘F(r)ictions’ strand of experimental film with a feminist, queer or trans focus. Lourdes is a market trader in Tepito, Mexico, who sells t-shirts from her stall in the barrio. As her cautious interviewer slowly draws out from her, Lourdes is implicated in a form of feminist politics that asserts women’s place and power in the community, faced with the intrusions and incursions of officialdom into a working-class community. At the core of Zaman’s film is Lourdes’s discussion of albures, a culture of speech in which sexual double-entendres are rife, and which she links back the coded speech of those pre-colonial Mexicans having to deal with the power and impositions of their Spanish conquerors. It’s an unassuming but deft work which asserts a view of women as active and confident, their agency rooted in communal solidarities. Now, people in Mexico are being battered by the pandemic. Artists’ videos might seem a slight and distant concern. Watching films from the recent past is a reminder of the chasm that has so suddenly opened up in the present, and that it’s only through forming new solidarities that people will be able to face it. What might new art look like in that mix? It’s still a blank screen, waiting for a signal.