From immersive installations by Heather Phillipson and Yayoi Kusama to retrospectives of Eileen Agar and Jean Dubuffet, the capital’s artworld emerges from lockdown

“Welcome back!” The voices of the ticket-checkers echo across the Royal Academy courtyard. Upstairs, Michael Armitage’s Paradise Edict (to 19 September) brings together 15 of the British-Kenyan artist’s large-scale paintings – multi-layered, often fantastical explorations of politics, history, myth and landscape. Armitage is known for referencing western art’s old masters, but this show goes wider: included are works by East African modernists who have influenced him – among them Meek Gichugu, whose No Erotic Them Say (c 1992), a painting of a wide-eyed woman entwined with a zebra, shocked the artist profoundly as a nine-year-old. Downstairs is David Hockney’s life-affirming The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020 (to 26 September), his second batch of iPad works, 116 in all – a reminder that the greatest thing about Hockney is his relentless experimentation.

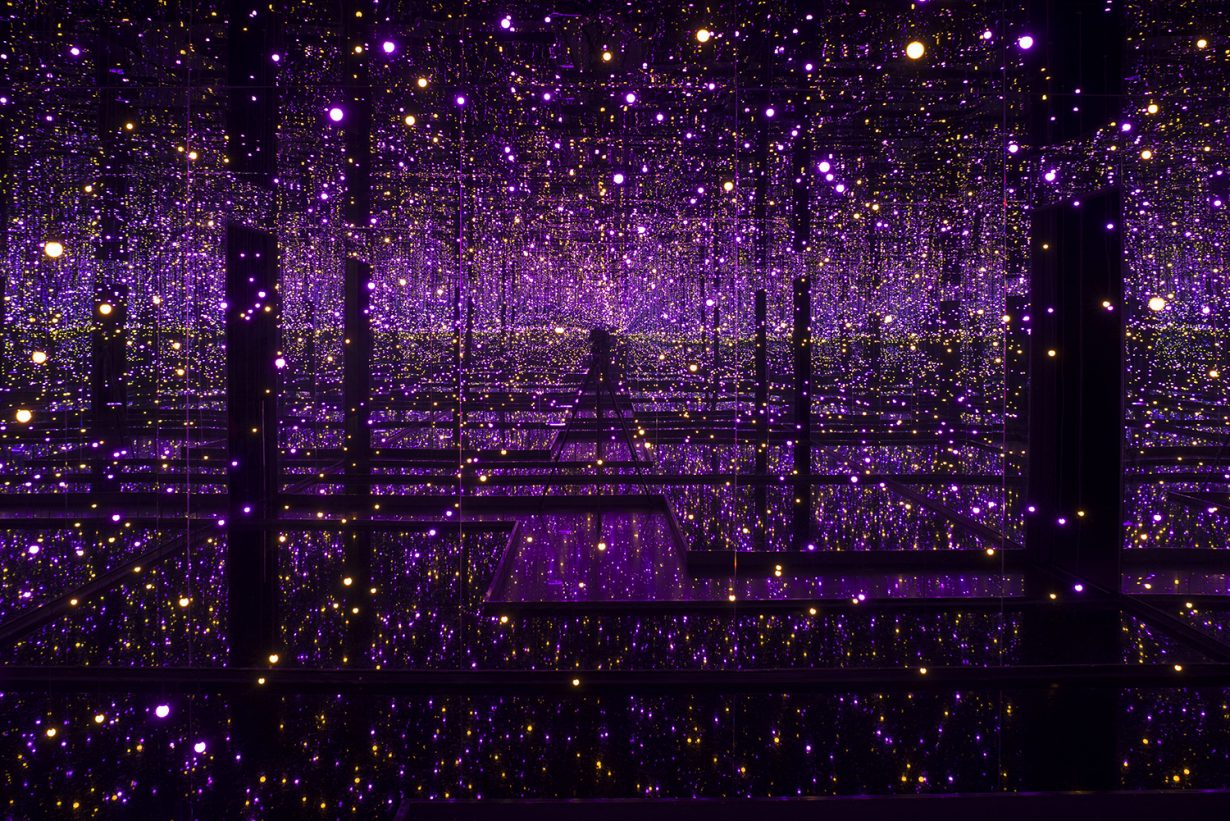

Across the river, Tate Modern has put on show Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Rooms (to 12 June 2022), one of which she created for the museum in 2012. Four months’ worth of tickets sold out almost immediately. “It is both exciting and nerve-wracking to reopen,” Tate’s director Maria Balshaw tells me. “But the sheer number of visitors who have booked this week has been enormously encouraging.”

Presented by the artist, Ota Fine Arts and Victoria Miro 2015, accessioned 2019. © Yayoi Kusama

If Hockney’s spring greens seem startlingly intense, Heather Phillipson’s apocalyptic vision, Rupture No 1: blowtorching the bitten peach (Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries, to 23 January 2022), leaves them looking subtle. Immersed in red light and eyeballed by zebras, monkeys and frogs, you slip between the legs of a torso-less giant to join a quartet of petroleum-barrel critters sucking diesel from a pond. The world turns blue, clouds rush by and you arrive finally at a crumbling corrugated outpost. Behind it a huge peach stands in for the sun.

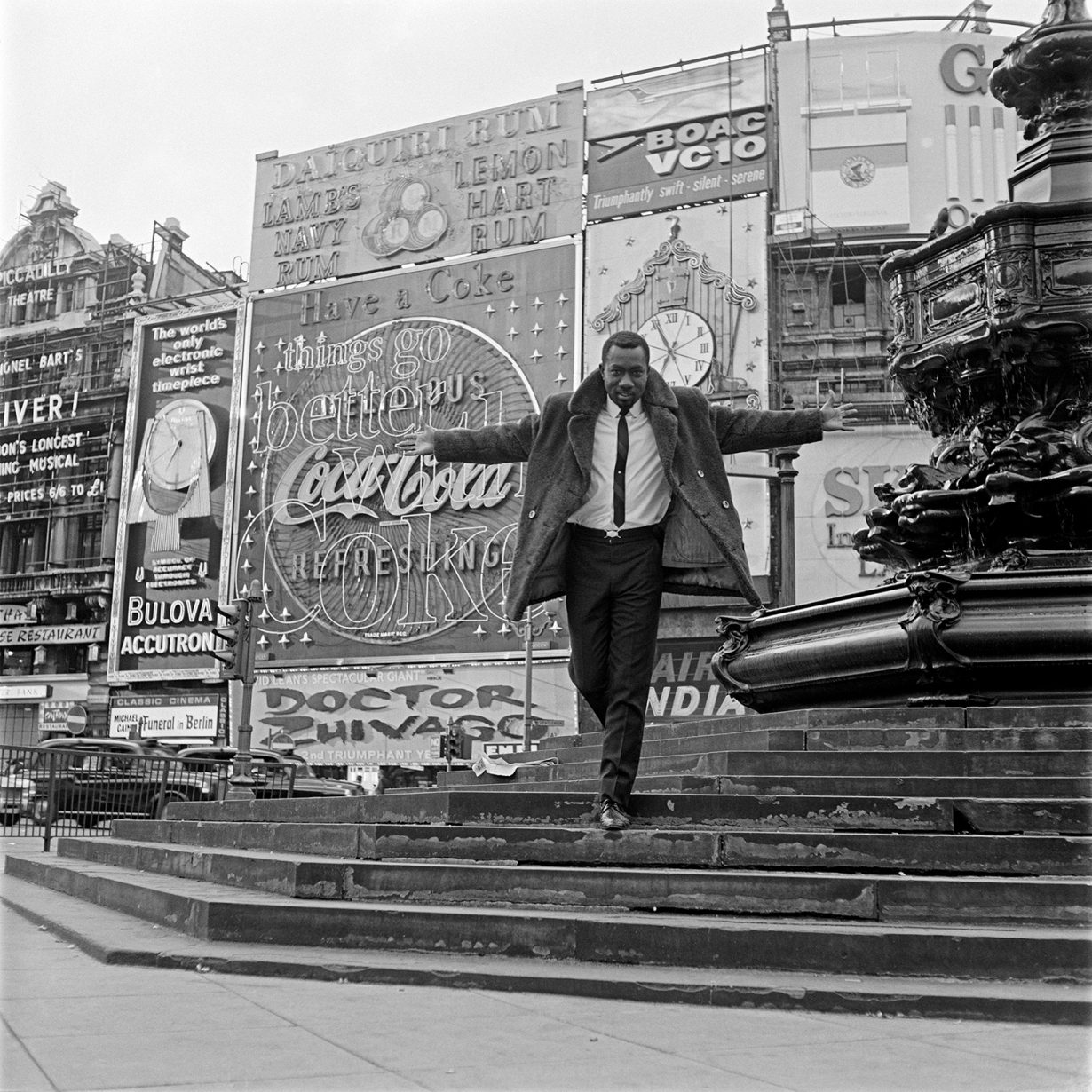

From colour to (mostly) black-and-white and the Serpentine’s latest celebration (to 22 October) of a pioneering artist late in their career: James Barnor, now 91. The show focuses on the period 1950 to 1980, during which the Ghanaian-British photographer moved between Accra and London, capturing Kwame Nkrumah in 1957 with the same easy empathy as three elderly ladies admiring his baby son Fred in Kilburn in 1966.

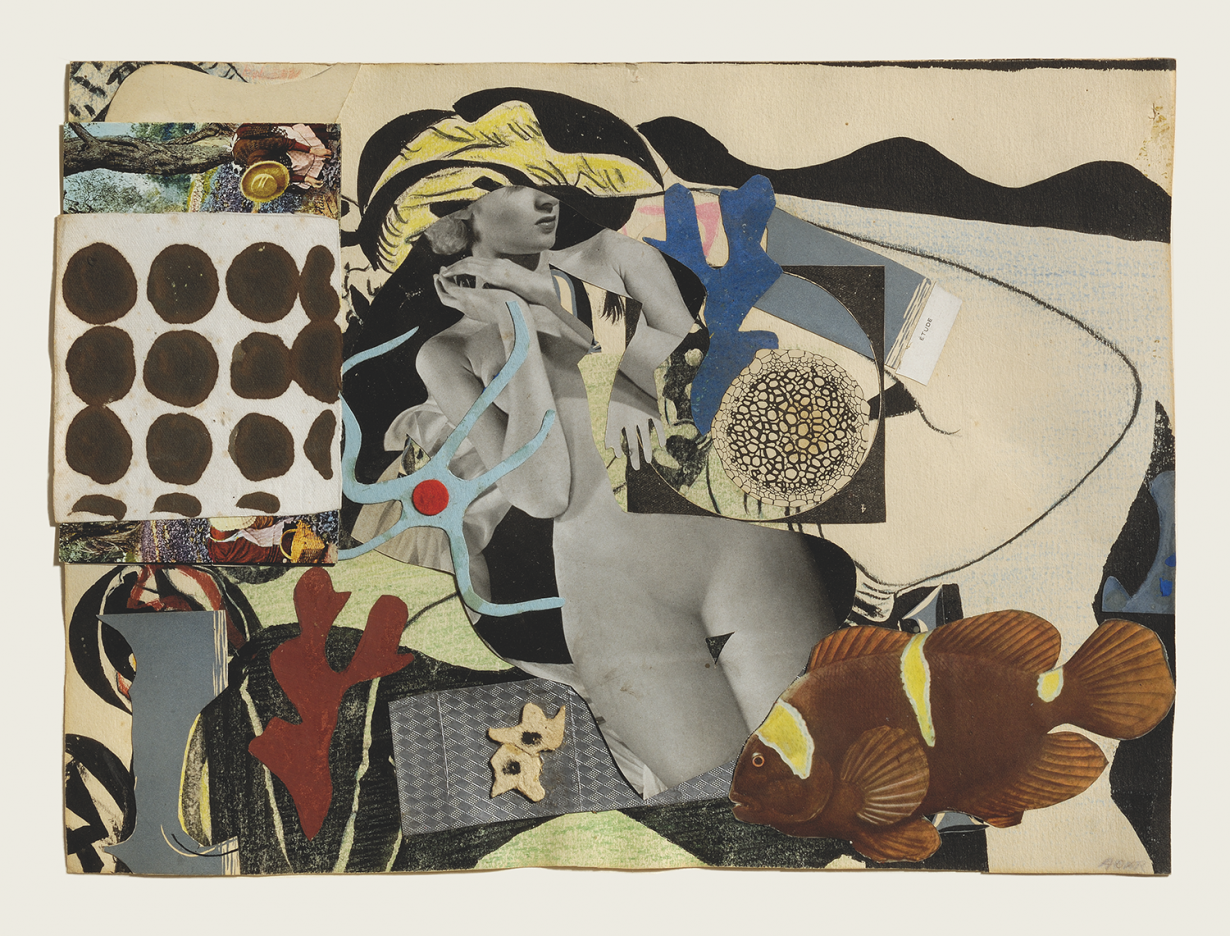

For London’s museum staffers, the closure brought on by the latest round of COVID-19 lockdowns opened up a space for reflection. “The pandemic has brought everything into sharper focus,” says Laura Smith, curator of Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy (Whitechapel Gallery, to 29 August). “I am grateful to have had time to stop and reflect on the impact an exhibition may have.” Feisty, sexy and multi-talented, Agar (1899-1991) was one of the few women to be included in the International Surrealist Exhibition in London in 1936. “As an anti-fascist and surrealist, Agar’s delight in nature and her feminist approach informed her ambition to develop a universal visual language that she didn’t waver from for 70 years. I think that is something we can learn from.”

For an artist who focuses on the interplay between bodies and their surrounding space, it’s no surprise that the lockdowns have fuelled new work from Yu Ji (Chisenhale Gallery, to 18 July). In Wasted Mud, the Chinese artist has cast figures from concrete and filled a vast hammock with rubble from a Tower Hamlets building site and objects from her Shanghai studio. She detects a vitality in what others dismiss as waste. The Barbican’s impressive Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty (to 22 August) suggests the French artist (1901-1985) was a kindred spirit. Eschewing conventional notions of beauty (particularly the classical female nude), he sought ‘the poetry of everyday life’, mixing glass, coal dust and pebbles into his paint and championing outsider art.

For beauty, though not of a conventional kind, seek out Igshaan Adams’s Kicking Dust (Hayward, to 25 July). Inspired by an ancient southern African dance, the artist has suspended exquisite cloud-like sculptures over floor weavings to evoke the traces we leave as we move. Drawing on the principles of Sufi mysticism, the weavings can be also read as self-portraits of the artist. Matthew Barney’s Redoubt (also at the Hayward, to 25 July) reimagines through film the classical myth of Diana and Actaeon in a snow-covered Idaho. Sculptures cast from burnt trees and shimmering electroplated copper engravings complete the exhibition. “For audiences who have been stuck inside looking at art on their computer, you couldn’t have two better shows to give you the tactile, physical dimensions that art speaks through,” says Hayward director Ralph Rugoff.

The pandemic has not been kind to the capital’s artworld, of course. COVID-19 has forced museums to cut back their activities and reduce costs. Border closures have affected their ability to borrow works. “We will have to adapt to survive,” says RA secretary and chief executive Axel Rüger. “However, what has been clear throughout the pandemic is the ability of cultural institutions to be sources of inspiration, solace, excitement and wonder in our everyday lives.” He sees a need to offer a programme with “a wider range of voices that people can see themselves in”.

At Tate Modern, in particular, the absence of overseas summer visitors will be felt. But it hasn’t lessened the Kusama frenzy. Those still without a ticket will have to move fast in September when more are released if they want their Instagram fix. In the meantime, better perhaps to pocket your camera phone and immerse yourself in these shows properly – in case another lockdown might be just around the corner.