A Song of Ascents at Hepworth Wakefield occupies a space between specificity and generality – to intoxicating effect

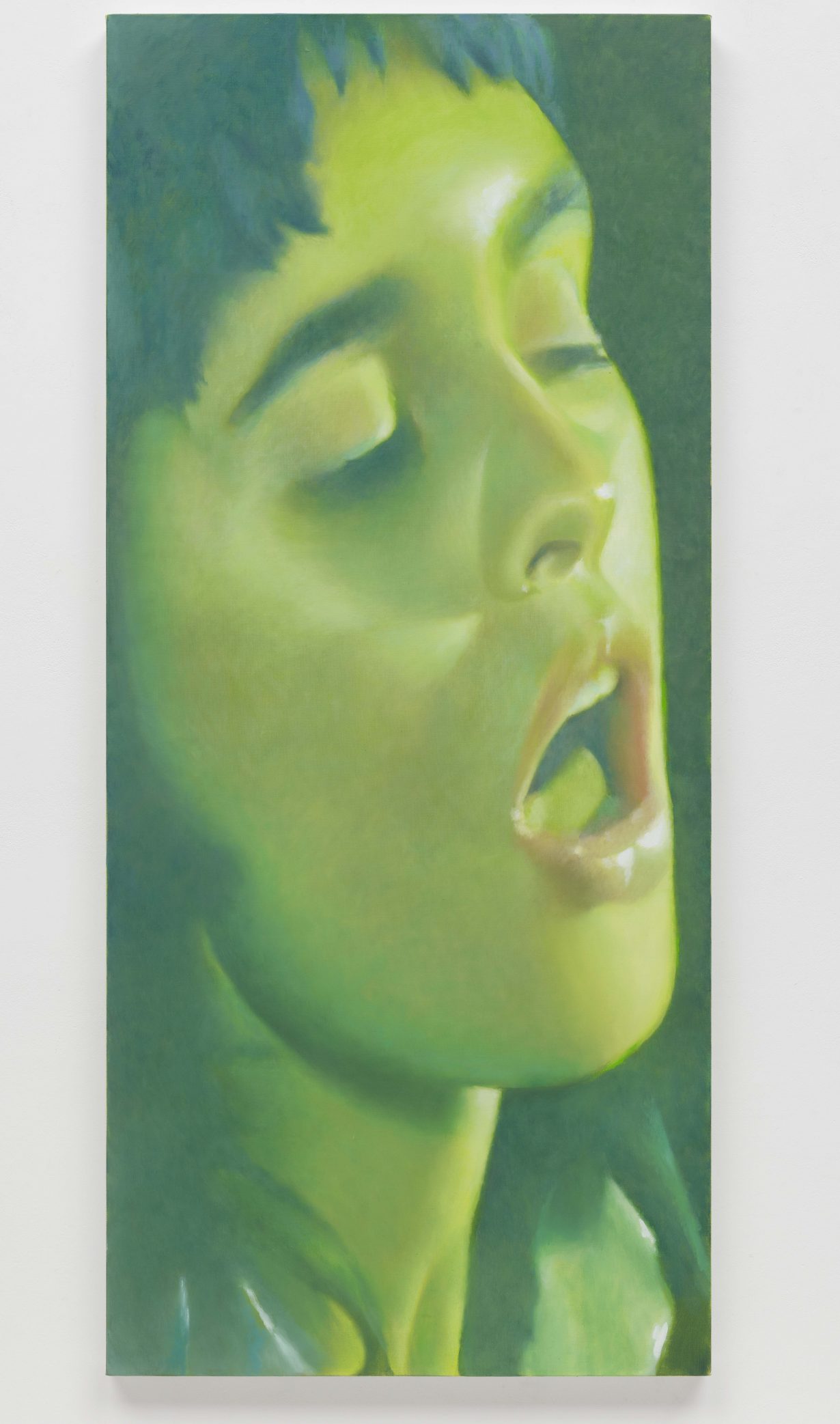

Louise Giovanelli’s huge paintings of curtains dominate this exhibition, filling the space with lifesize, or even larger-than-life, sparkling and electric-coloured drapes. Looking at them on their own, I was reminded of school auditoriums, old theatres and kitsch Victoriana. But the other works in the show point to a more specific reading: they show women drinking, kissing, gasping, shaking their hair under bright lights and, in one case, being covered in pig’s blood. Taken together, they evoke the seedy-but-glittering mood of drinks, drugs, dancing and the euphoria they fuel.

Giovanelli’s oil paintings pulse with a neon luminosity that comes both from her palette and her painstaking paint handling. Some of her smaller works, like The Painting’s Landlady (2024), a closeup of a glowing face seen through a glass of something strong, have a speckled, pointillist impasto. Her canvases of giant drapes are different, their surfaces mimicking the matt softness of velvet with careful layers of paint. The hair paintings feel similar: canvases filled with a soft, complex texture that is entirely out of context: not even the back of a head, just hair.

Although the exhibition catalogue proffers a thematic narrative about drinking and club culture, especially during the 1980s and especially in British working men’s clubs, the magnetism of these works, to me, is in their lack of narrative. The curtains loom over the show in both size and allure, and the layered potential readings of these are many: the promise of spectacle offered by a drawn curtain, the invitation to perform, the mystery of what might be hidden, the drama of worship, the mixture of aristocratic and working-class visual language, the heritage of the Renaissance and its obsession with drapery.

That array of readings, which can stand alone or overlap, all leave the viewer with a sense of the works’ opacity. Stoa (2024), the biggest painting in the show, is a vivid green curtain that seems to leap off the wall, with highlights in electric red. It occupies a space between specificity and generality that invites transcendence over the mundane – but towards what, exactly, is left open. Like icons or other religious images, the space these curtains both create and hide feels familiar but special, human but not quite earthly, legible but not fully knowable. It sits on the line between the profound and the banal: unlike the grimy, characterful clubs and pubs it is inspired by, this painting, like all those in the exhibition, is pristine. There is a tension between their cold veneer and the hot allure of mystery they evoke that makes them intoxicating – like celebrities, or classical sculpture.

Giovanelli says she is an atheist, but her work is about the human need for worship or ‘glimmers of elevation’, as she put it in an interview with curator Marie-Charlotte Carrier in the exhibition catalogue. ‘A Song of Ascents’ refers to Psalm 130, also known as ‘De Profundis’ – and additionally the title of a famous letter by Oscar Wilde to a former lover in which he reflects on faith, and the lack of it. The desire for something to worship, for a place to direct our obsessions or queries, is deeply human. The void that has opened in the postmodern West leaves many floundering for that kind of intangible, vaster-than-us solace. Giovanelli sees that absence, and while her works don’t really fill it, they are about the depth of our yearning for something that could.

A Song of Ascents at Hepworth Wakefield, through 21 April

From the January & February 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.