Raven captures the undoing and remaking of the American West’s landscape, and why the process is both simpler and more complicated than it appears

In stories told along the Klamath River, salmon are not simply a food source but are also considered kin who choose to give themselves to humans. Running from Oregon through Northern California before joining the Pacific, the river once supported some of the richest salmon runs on the West Coast. For the Yurok, Karuk, Hoopa, Shasta, Klamath and Modoc peoples, those fish (the Chinook and coho species) were inseparable from spiritual practice, diet, health, tradition and economy. Their yearly return up the river represents a cycle that binds water, land and people together. The fish are greeted with ceremony, thanked and then mourned when they depart for the sea. To see salmon is to know that lifecycles continue.

When construction of the first hydroelectric dam on the Klamath began in 1903, the cycle was broken. Three more such dams were built on the river’s mainstem between then and 1964, resulting in the widescale disruption of the river’s natural flow. Concrete walls blocked the fish from reaching their spawning grounds; reservoirs warmed the water, which encouraged the breeding of parasites and sped up the growth of toxic algae blooms; sediment clogged the riverbed. Lower sections of the river gradually became starved of vital nutrients. By the start of this century the once-thriving runs had collapsed: in 2002 tens of thousands of adult Chinook salmon were seen floating dead in the lower river. (The highest estimates put the number at around 70,000.) The loss was ecological, cultural and social. Ceremonies tied to the salmon could not be performed. Food sovereignty was eroded.

The removal of four dams – J.C. Boyle, Copco 1 and 2, and Iron Gate – was the largest project of its kind in US history. It was completed only in 2024, after decades of campaigning by tribes and environmental groups, lawsuits against the power company PacifiCorp (which owns the four dams) and a long process of negotiation with state and federal agencies. That removal is often framed as an environmental triumph, but it is also, in part, the undoing of an infrastructure built on a logic that finds provenance in the expansionist concept of Manifest Destiny (which, in short, treated First Nations rights as expendable). To some, a river is merely another natural resource to be exploited, diverted for industry, tapped, contained, controlled; for others, the river is part of a symbiotic ecosystem, a giver of life that should be treated with respect.

American artist Lucy Raven produces photography, video, sculpture and installation, often exploring systems of power. Her new videowork, Murderers Bar (2025), takes the abovementioned history as its backdrop. The title refers to the nineteenth-century name for Happy Camp, a town on the Klamath, and points directly to the violence of settler expansion: massacres, land seizures, the gold rush. Raven positions the dams within that lineage as a structure that extends a colonial worldview, one in which a river is to be tamed and exploited. But Murderers Bar does not explicitly narrate that history, nor does it speak on behalf of those who lived it. Instead it drops viewers into the process of the Copco 1 dam’s dismantling, so that the material as much as the conceptual weight of the structure – and of its destruction – becomes the focus.

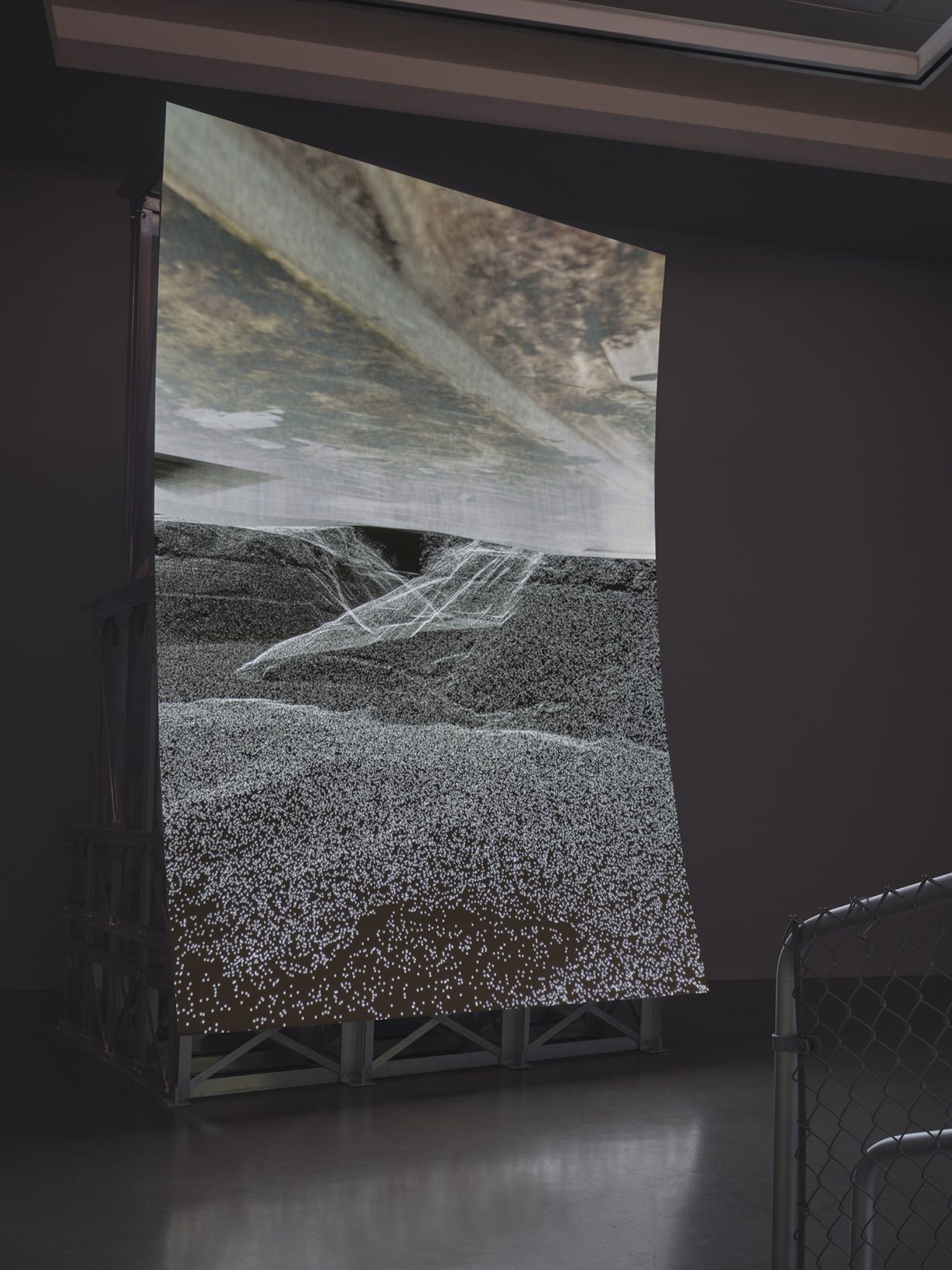

Projected on a freestanding aluminium frame, the 42-minute work immerses the viewer in shifting registers of image and sound. Dipping beneath a digital rendering of a brown body of water in an abstract landscape, viewers are taken on an ‘underwater’ tour of what appears to be the natural winding path of a riverbed that has been digitally modelled in 3D. (And based on data collected by the Yurok Tribe Fisheries Department.) What is visible above is not the same as what’s actually below. As the viewpoint resurfaces, the video switches to real footage of the reservoir trapped behind Copco 1. Vast aerial shots pan the area around the dam, in part rendering it as set of abstract outlines. These sequences, shot from a distance, carry a kind of bureaucratic detachment, evoking the cold gaze of surveyors and regulators. Between these is more straightforward documentarylike footage of workers and machinery: shots of the dam and its surrounding power plant, hard hats and high-vis vests, men drilling holes and shoving sticks of explosives into the concrete wall of the dam. In one scene, a worker stands at the base of the dam, and the scale of the manmade structure is colossal. Murderers Bar reaches its catalyst early on, with an explosion, a release of water through – given the scale and volume of water contained on the other side – what appears to be a too-narrow tunnel. Watching the pressure of the water flow is a visceral experience; it’s as if watching oxygen flood the alveoli of a pair of air starved lungs. That embodied feeling is transmuted via closeup shots that skim the surface of the water, duck beneath and resurface – locating the viewer in the body of a fish. The sensation is of moving with the salmon themselves, catching light in the murky depths of the river, yet disoriented by its unsettled sediment.

Digital animations intersperse and occasionally overlay the footage: apart from the 3D renderings of the riverbed, a set of radar range rings floats over footage of the river; the movement of its dial gradually turns the footage from colour to black and white. These insertions and the extreme differences in viewpoint mark different ways of ‘knowing’ a landscape – to live in it, to fight for it, to render it as data, to control it. Raven refuses to reconcile them. Instead she makes the viewer toggle between perspectives: surveyor, salmon, worker and witness. The result is a fractured vision that mirrors the sediments and layered history of the river itself.

Murderers Bar is the concluding part of Raven’s multimedia project The Drumfire (2020–25), which reshapes the Western landscape genre. The Drumfire does this by focusing on how the landscape’s natural materials are placed under pressure, broken apart, reconstituted. In a new documentary about the series and more specifically about the making of Murderers Bar, titled Lucy Raven: Pressure & Release (2025), the artist describes this as an enquiry into the “kind of state change that creates structural, or in some ways infrastructural, violence on the landscape”. Ready Mix (2021), the first video in the series, follows the mining of aggregate through to the production of cement at a plant in Idaho, where explosions, grinders and mixers turn rock into the base matter of construction. The two Demolition of a Wall films (Album 1 and Album 2, both 2022) use highspeed cameras to record the shockwaves of controlled blasts detonated in the landscape at a military site in New Mexico, while the blast itself is left out of shot.

Sometimes Raven approaches her subject from a more oblique angle: while making Demolition, she turned to photography. Her resulting photobook Socorro! (2023) is named after the town in which the explosives range is located; meaning ‘succour’, Socorro was named by sickly Spanish settlers who were provided water by the Piro Native Americans. Raven worked with the ballistics lab at New Mexico Tech to produce shadowgrams of projectiles fired into a sealed chamber – abstract grey images of airflows, inky-looking blooms and grids on photosensitive paper pockmarked with piercings from the impact of the projectiles’ contents. The images in Socorro! hint at the ongoing violence that’s shaped the American West while also recalling the history and use of photography in military science. And then there is Depositions (2024), a series of five works on silk Raven made while researching Murderers Bar: to create these works she constructed water chambers out of soil and cement, lined them with silk organza, then poured water in and let the water gradually drain away. Sediment shifts across the fabric, leaving behind delicate stains and residues that appear like an abstract landscape. But more literally, they represent the slow inscription of history onto a surface – the way water records both passage and obstruction, the way systems of extraction and containment leave marks, even when the structures themselves are dismantled.

Across these works Raven often uses surveillance cameras, infrared imaging, industrial processes and digital mapping – the very technologies that hide or rationalise systems of control. And in doing so, she lets the strangeness, the distortion and the sensory qualities of these technologies become the texture of the work. Manifest Destiny also maintains a spectral presence throughout the project: the ideology that justified westward expansion, displacement and conquest, written into the dams, mines, military bases and ballistic labs that shape the work.

As with the three earlier videoworks in The Drumfire, to watch Murderers Bar is to move between scales: from the technological distance of the aerial survey, to the embodied perspective of water rushing past, to the brute-force labour of demolition. Each view destabilises the others. Together they produce an image of the river that is unsettled, contradictory, unresolved. That refusal of closure matters, because while the Klamath now runs more freely, its future remains precarious: the release of the reservoirs has revealed altered habitats, and there is lingering contamination from the industrial plants. Restoration does not immediately mean resolution. The power of Murderers Bar lies in holding the viewer in suspense between the fractured imagery of ruin and renewal, in making palpable both the violence of infrastructure and the fragility of undoing it, and how power is built and how it comes apart, leaving uncertainty in its wake.

In October 2024, just months after the final reservoir was drained, the first Chinook were spotted moving through stretches of river that had been blocked for a century. Their passage is a sign of recovery, but it is not a clean slate. The land carries indelible damage. The last of Raven’s video footage shows the extent of the drowned land behind the dam: its draining reveals the remains of long-submerged trees, vast swathes of silt-clogged land, ancient spawning grounds that need to be revived and an altered landscape that communities who live beside the Klamath must now navigate. Murderers Bar holds us in that double vision – the flow of water resumes and salmon are returning to the river, but it’s also a reminder that while cycles of life begin again, the scars left behind take longer to heal.

Murderers Bar is on show as part of Lucy Raven: Rounds, at The Curve in the Barbican, London, 9 October–4 January. The film will also be on view at The Power Plant, Toronto, 7 November–22 March; the documentary Lucy Raven: Pressure & Release can be watched for free

From the October 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.