What is a photograph? This is the (admittedly unoriginal) question Akram Zaatari poses in this excellent exhibition packed across two gallery spaces.

The first venue is largely given over as a screening room for the artist’s 42-minute film, On Photography People and Modern Times (2010). Formed of two synchronised projections, showing a desk in what the press release reveals to be the Arab Image Foundation, a nonprofit research institution that Zaatari formed along with fellow artist Walid Raad and photographers Fouad Elkoury and Samer Mohdad in 1997, from bird’s-eye and front-on views respectively. The desk is occupied by a digicam and monitor (the screen of the monitor invisible from one perspective, the screen of the digicam similarly obscured from the other), which each display video interviews, recorded by Zaatari between 1998 and 2000, with various retired studio photographers (or their relatives) from across the Middle East.

We see his subjects leaf through their old photographic work, which in most cases seems to date back to the 1970s. Their reminiscing is largely anecdotal. Teased out via the dialogue, however, are differing meditations on the nature and affect of a photograph.

One interviewee posits the photograph as a means of capturing the present, “like a reflection in the pool”, he says in thickly accented English. In another conversation, the daughter of a deceased photographer recalls all the props and costumes kept at her father’s studio for customers to dress up in, foregrounding the photograph as fiction; conversely, a third subject looks wistfully at an old photo of friends and family and notes that “very old memories” are being reconstructed by the image.

A convivial chap remembers the occasions when one of his customers branded the portrait he had taken of them a “lie” because the camera had not captured the subject’s personal (mis)perception of their appearance. “It simply captures what one is like; it acts as a mirror,” the photographer remembers explaining to the angry sitter.

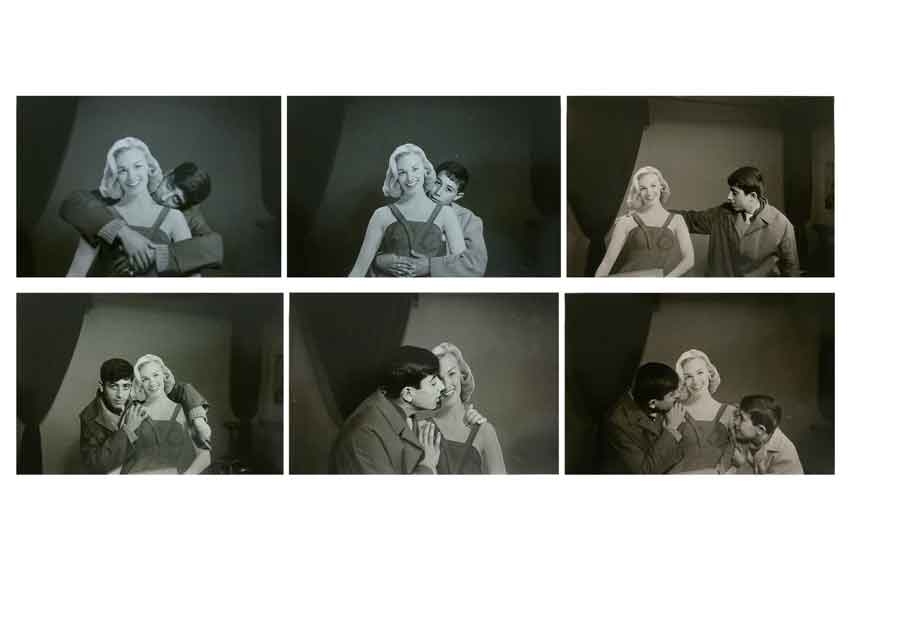

If On Photography People and Modern Times poses questions, then something of an answer is provided by a selection of works presented in the gallery’s second space – among them an installation of short Super-8 films, HD videoworks projected onto the walls or displayed on Kindles and iPads, black-and-white portrait photographs developed from archive negatives (smiling wedding photographs, grinning boys larking about with a cardboard cutout of a glamorous Western starlet, demure young ladies) and new still-life colour photography shot by Zaatari himself, either wall-mounted or displayed in archive drawers.

All of these works in some way document vintage imagemaking equipment or portray an old photography studio. While further reading reveals the subject of this work to be Studio Sheherazade, a photography business belonging to Hashem al-Madani, a Lebanese portraitist who worked in the city of Saida from the early 1950s (and in whom Zaatari has had a longstanding interest), nowhere in the actual exhibition is this fact revealed. Instead the viewer is left to treat these documents as mysterious archaeological artefacts, around which we are free to weave our own historical narrative. When coupled with the knowledge of the turbulent, traumatic chapter of Lebanese history that unfolded concurrent to this studio business’s period of operation, the idea that an image can form the basis of unreliable, or indeed fictive, memory, is a politically poignant one.

This article was originally published in the March 2014 issue.