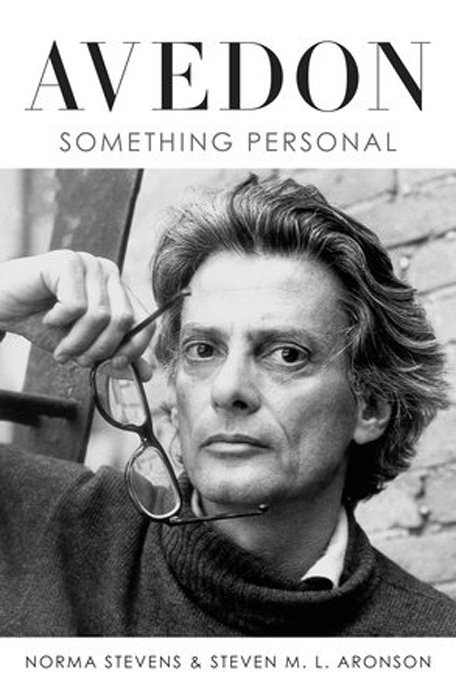

“All photographs are accurate,” Richard Avedon once said. “None of them is the truth.” The same could be said regarding biographies, but especially this recent doorstopper devoted to the legendary photographer. An entertaining but slapdash book penned by the artist’s collaborator and business partner Norma Stevens and writer Steven M. L. Aronson, the breezy 700-page volume proves substantial in the same way Perez Hilton is revealing.

A succès de scandale even prior to publication because of reports that the twice-married Avedon was bisexual and had affairs with, among other boldface names, his high school classmate James Baldwin and the film director Mike Nichols (according to Stevens and Aronson, Avedon and Nichols had plans to leave their wives and elope to ‘Gay Paree’ but eventually ‘chickened out’), Something Personal found public repudiation immediately after hitting the bookshelves. The book’s chief challenger: the Richard Avedon Foundation, which alleges that the biography is ‘filled with countless inaccuracies’ and, additionally, is based on a work of fiction Avedon was working on when he died.

Presented as ‘equal parts memoir, biography, and oral history’, Something Personal is less a traditional biography than a collection of reminiscences, many of them from celebrities, ex-celebrities and the celebrity-adjacent. Crammed to bursting with flashbacks from figures like Calvin Klein, Brooke Shields, Naomi Campbell, Kelly LeBrock, Bruce Weber, Jann Wenner and the mononymous hairdresser Oribe, the book floats on clouds of vernissage gossip, dinner-table backbiting and after-party innuendo. Tellingly, the relentless march of trivial anecdotes quickly forces a sobering realisation – one does not need to be a millennial to feel blasé about the better-known titanosaurs of the pre-Twitter and Facebook age.

Which is not to say that more crucial stories about the famous photographer’s life and career are without interest. Avedon was – together with Irving Penn, with whom he kept up a dogged Picasso-Matisse rivalry – the most famous fashion photographer of his time. His renown notwithstanding, he also struggled to be taken seriously as an artist. Stevens was particularly well placed to document what the photographer himself believed was a textbook case of acute cognitive dissonance.

Avedon attended to his personal history like Edward Scissorhands tending a holly bush… But, claims Stevens, the artist left the matter of telling the truth of his life to her

As Avedon’s longtime studio director, she spent 30 years in the photographer’s sparkling company (the man seemingly knew everybody and everything on at least six continents). She also helped orchestrate both his increasingly demanding and lucrative day-job and the museum exhibitions he craved like a mother’s love (Anna Avedon was, predictably, adoring, even smothering). No wonder the celebrated photographer remains, to date, the only artist to have had two Metropolitan Museum of Art retrospectives during his lifetime.

Avedon attended to his personal history like Edward Scissorhands tending a holly bush. Into his eighties he submitted, unsolicited, new obituaries to The New York Times several times a year (his greatest fear, Stevens writes, besides getting fewer column inches than Penn, was dying the same day somebody ‘even bigger’ kicked the proverbial can). But, claims Stevens, the artist left the matter of telling the truth of his life to her. ‘Don’t be kind – I don’t want a tribute, I want a portrait,’ he supposedly said to her. ‘Make me into an Avedon.’ One wonders, after reading the umpteenth anecdote about the man’s fastidiously secretive nature, whether he really intended for his friend and confidante to let it all hang out quite so flabbily.

A master portraitist who was not above staging his warts-and-all photographs of, among other subjects, movie actors, politicians, writers, civil rights workers, ranch hands, newly married couples, swamis, ex-slaves and wide-beamed Daughters of the American Revolution, Avedon subscribed to the idea that his sitters’ peculiarities crucially also matched his person. ‘My portraits are more about me than they are about the people I photograph,’ he said. With Something Personal, a similar phenomenon is at work. Charming and engaging at times, like Avedon, the book is also unfortunately glib, windy and unreliable – like its writers.

Spiegel & Grau, $40 (hardcover)

From the March 2018 issue of ArtReview