Duras’s cinema, restless and wilfully obtuse, interrogated the foibles of human expression in a world locked by politics and money

Cinema ‘knows that it can never replace the written text’, wrote the writer and filmmaker Marguerite Duras in 1977; nevertheless, it ‘sets out to replace it’. It begins, in other words, with certain defeat and, sustained by this tension, makes its way from there. What does it mean to make a practice out of dissatisfaction, of failure?

Let Cinema Go To Its Ruin, a retrospective showing at London’s ICA through 25 August, brings together the 19 films Duras codirected, other directors’ interpretations of her work and a selection of shorts and television interviews. In doing so, it must confront Duras’s relentlessly obtuse self-reflexivity. In the programme, curator Daniella Shreir positions Duras firmly and deftly in her sociohistorical context, including her formative experiences of colonialism and world war: born in 1914 in Gia Định, which, now Vietnam, was at the time part of French Indochina, she moved to Paris at nineteen and survived the Nazi occupation as both an employee of the Vichy government and a member of the French Resistance; her then-husband, Robert Antelme, was deported to a concentration camp in 1944. Later, she joined, then left, then was expelled from the French Communist Party (PCF), though she told The New York Times in 1991 that she remained a Communist: ‘There’s something in me that’s incurable’.

Duras, who died in 1996, lived a life we can understand as chronically – incurably – political. But our understanding of her also exists, crucially, within the iterative and less legible patterns of her life’s work: not only was she frequently adapting her own writing for the screen, but she repeatedly returned to and remade her own cinematic material, as if dissatisfied with its original manifestation. In 1967 – the year she made her directorial debut with La Musica – she declared that a film can ‘only ever be weaker’ than a piece of writing. ‘My own “imaginary cinema” of Madame Bovary’, she observes by way of example,‘is unparalleled.’ And yet she often declared her desire to ‘abandon’ literature for cinema. ‘I can’t read novels at all anymore’, she said in 1968. ‘Because of the sentences.’ This is the labyrinth illustrated by Let Cinema Go To Its Ruin: constant production, self-negation, revision, ad infinitum.

The ICA retrospective takes its ruinous title from a line in a piece Duras wrote to accompany the release of her 1977 film Le Camion, which stages her disillusionment with Marxism and her bitter falling-out with the PCF via an experimental dialogue between a hitchhiking woman and a Communist lorry driver (played by Gérard Depardieu). The piece, which is also titled ‘Joy: We Believe: We Believe in Nothing Anymore’, insists that there is:

No longer any use in the make-believe of socialist hope. In the make-believe of capitalist hope. No longer any use in the make-believe of future justice, be it social or fiscal or any kind of justice. The make-believe of work. Of merit. Of women. Of the youth. Of the Portuguese. Of the Malians. Of intellectuals. Of the Senegalese. No longer any use in the make-believe of fear. Of dictatorship over the proletariat. Of freedom. Of your nightmares. Of love. No longer any use.

This litany of refusal then moves into an explicit consideration of the relationship between filmmaking and writing: ‘Cinema stops the written in its tracks and deals a death blow to its descendent: the imaginary. Indeed, this is its virtue: to switch off, to put a stop to make-believe.’ In the film itself, this is quite literally realised: rather than depict the events of the narrative, it shows instead Depardieu and Duras sitting at her table reading the script for the film that would have been, interspersed with shots of the titular lorry.

If the imaginary is dead, what, onscreen, replaces it? Engaging with Duras’s work ‘often involves subjecting oneself to a degree of confusion and ambiguity’, Alice Blackhurst writes in her introduction to My Cinema – a 400-page-long collection of Duras’s writing and interviews (published this year and translated by Shreir). ‘The writer’s inconsistencies can sometimes jar within the margins of a page, or even the space of a few sentences, showcasing a mind both brilliant and grappling with an ever-evolving catalogue of contradictions.’ This is certainly true, too, of Duras’s films. In Blackhurst’s words, Duras – who published her first novel a quarter of a century before she made her first film – never managed her ambition of abandoning literature by turning to cinema, but rather ‘accessed another medium through which she could generate even more text’. Neither representative or realist, her cinema dwells in experiment and abstraction – it requires interpretation – while her writings about it identify, again and again, a central paradox: she kept on making cinema and kept on denigrating it, investing the form itself with a kind of self-reflexive paralysis.

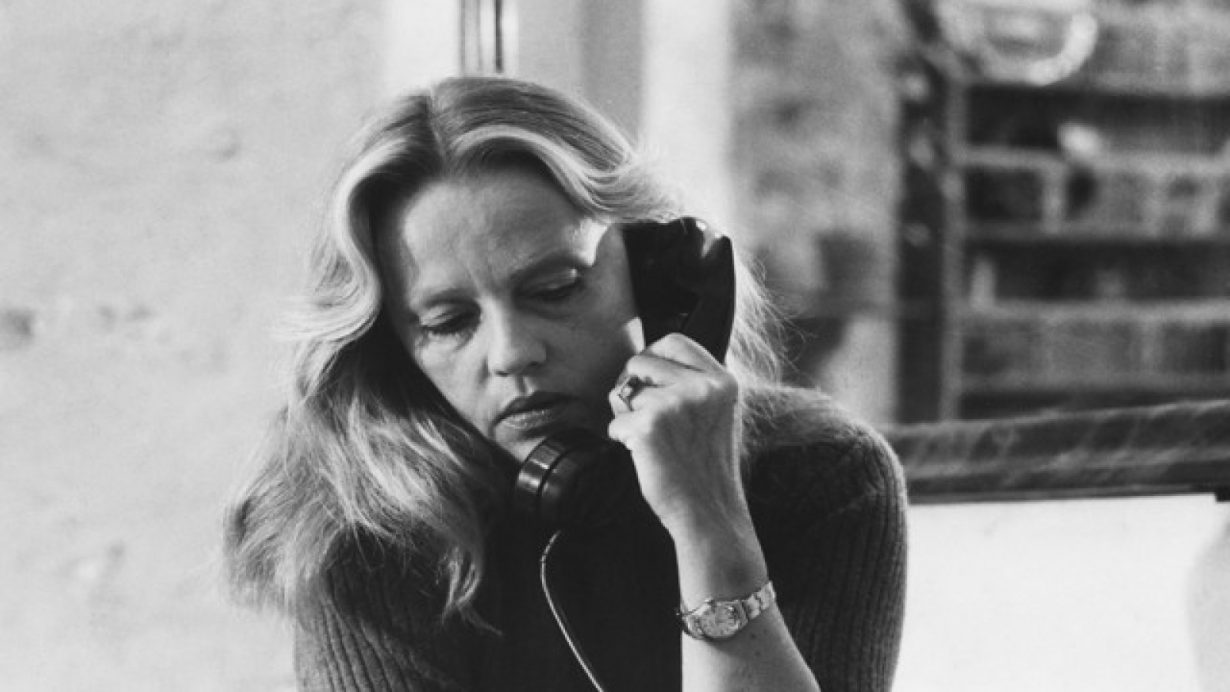

The ICA season begins with an ending. La Musica (1967), an adaption of her 1965 play of the same name, stages the first meeting in three years of an estranged couple (Delphine Seyrig and Robert Hossein) whose divorce has just been formalised. Retrospectives of this size require the viewer to find their own path through them, and as I made my way through Let Cinema Go To Its Ruin, the shape that began to emerge – haphazardly and ambivalently – was an unexpectedly matrimonial one. The couple form, and its discontents appear repeatedly across Duras’s filmography as she moves towards a more experimental mode of cinematic expression. Marriage is a kind of text, too: a form that confines and defines, that needs reading and is always at risk of being overdetermined by its contexts and histories. In ‘An Inquiry into Truth’, an interview assumed to be with Jules Dassin in 1966, collected in My Cinema, Duras elaborates on her theory of matrimony:

Power ‘has’ you every time, and it doesn’t matter what kind of power; marriage is an exercise in power over lovers. There is pressure in the institution of marriage. People say my wife, my husband; people are married by an exterior power, meaning society.

The institution of marriage, in other words, is itself incurably political, as well as literally chronic: in succeeding in containing desire in a socially acceptable form, it legislates against it.

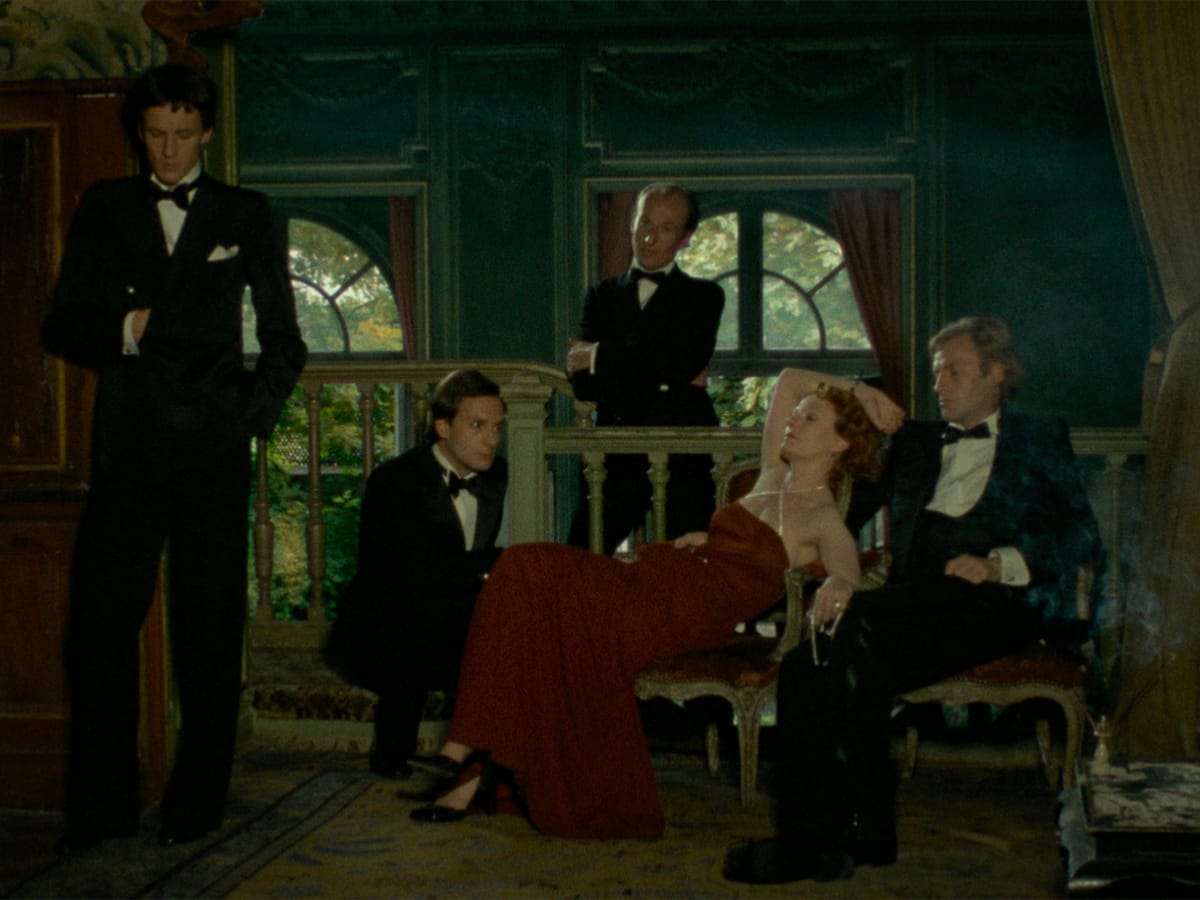

In La Musica, the dissolving relationship is a relic of recurringly thwarted communication; in this way, they remain husband and wife. Even as the couple’s torturous dialogue promises cathartic revelations, truthful disclosure is problematised, and then discarded: the husband, urgently entreating his wife to tell him the truth, acknowledges he requires the form of revelation rather than the thing itself. “Make it up if you want, but still tell me,” he says. Writing about the film in Cahiers du Cinema, Duras observes that their final encounter ‘no longer bears the traces of any grievances or wrongdoings. All wrongdoings and quarrels have evaporated. With the termination of married life, at last there is no longer anything to obstruct feeling.’ This happens after both members of the couple have admitted to harbouring the desire to kill each other. Matrimony and death are equated again and again in her work: in Jeanne Moreau’s claustrophobic death drive in Moderato Cantabile (1960); in the symbolic forest of Destroy, She Said (1969); in the violence encroaching on the domestic in Nathalie Granger (1972); and, most famously, in the deferred adulterous suicide of Anne-Marie Stretter, the woman defined entirely by her role as the ambassador’s wife, in India Song (1975), whose erotic, imperial lethargy is described in the film as a leprosy of the heart and of the soul.

Marriage is also something that makes a practice out of chronic dissatisfaction. In an interview with Le Monde about La Musica, Duras asks, ‘What is infidelity if not fidelity to love?… within these endless ends, there is space for endless revival.’ Endless revival is a poisoned chalice: the marital contract, for Duras at least, transforms the novelty and spontaneity of desire – that first moment of erotic connection that both lovers in La Musica go fruitlessly in search of amid the ruins of their marriage – into routine, a kind of living death of the heart. Nowhere is this as stark as in Baxter, Vera Baxter (1976), a mesmerisingly bleak film that takes place in an empty summer villa in which Claudine Gabay as the title character recounts her profound malaise to a stranger, played by Delphine Seyrig, uncannily soundtracked by looping party music from a neighbouring house. Baxter’s existential crisis is at heart a marital one: in a text written for the film’s press kit, titled ‘Witches’, Duras writes of Baxter’s life as one delimited entirely by her relationship with her husband, Jean, who was friends with her brothers and whom she has known for ‘her whole life’ when she marries him aged twenty: ‘for eighteen years, nothing has happened to Vera Baxter, except for her love for her husband – except for the fact of having been faithful to her husband for eighteen years’. This fidelity makes ‘duration’ the ‘event’ of Baxter’s life, a ‘uniform duration that marches straight towards death’. Immobility and stasis: the opposite of passion. She shares her name, we learn at the end of the film, with the wife of a crusader, burned as a witch a thousand years ago – an icon of abandonment.

Marriage is an economic condition – ‘Vera Baxter’s existence’, Duras writes, ‘might only be made intelligible through the rows and columns of a bank statement’ – and even during the periods in which Jean has temporarily left his wife for a new woman, he sends Vera cheques to cash: ‘he has never forgotten to send the signal that the marriage is still carrying on somewhere, somehow. Money. Money, together.’ (Those with expertise in the painful art of loving a married person know of the power of the financial structures of conjoinment that really keep the couple together. In the face of that steadfast transactional bedrock, desire doesn’t stand a chance.) The betrayal at the heart of Vera Baxter’s story demonstrates the inseparability of the conjugal and the financial: Jean becomes overcome with the desire for Vera to sleep with someone else, and so he ‘puts his wife up for sale’ for the cost of the rental of a summer villa, something Duras describes in an interview with Caroline Champetier as ‘rape’, given that Vera does not ‘go towards the freedom of desire of her own accord’. Trapped in her modernist glass house, without any form of forward propulsion, the cuts to the Atlantic Ocean offer respite for the viewer but never for Vera herself: she is enclosed in a reflective interior that never affords the possibility of submersion.

The ‘freedom of desire’ exists, in Duras, only up until the point of its realisation: as soon as an encounter actually occurs, the walls start closing in. It would be a mistake, however, to assume that this was the end of the story. Towards the end of the Le Camion text, the refrain ‘we believe in nothing anymore’ is defined as a form of ‘joy’. ‘No longer any use in your make-believe,’ it continues. ‘No longer any use. We must make cinema from this knowledge: from there no longer being any use in make-believe.’ Like marriage, which starts with the twin finalities of consummation and restriction, cinema, for Duras, begins with an ending, with the generative void. There are glimmers of movement, however: refusal opens as well as closes.

Let Cinema Go To Its Ruin closes with a screening called ‘Duras and Children’, bringing together her last film, Les Enfants (1984), with Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet’s adaptation of Duras’s children’s story En rachâchant (1982) and a short film Duras made for French television, Les Enfants et Noël (1965). In Les Enfants, which she cowrote with Jean-Marc Turine and her own son, Jean Mascolo, seven-year-old Ernesto (played by a thirty-eight-year-old Axel Bogousslavsky) refuses to go to school, an allegorical critique of the French education system as well as bigger, more general targets: she described it as ‘an endlessly desperate comedy whose subject has something to do with knowledge’. A desperate comedy starring an adult man reinhabiting his youth is hardly the final film we might expect from an artist who had declared that there was no longer any use in make-believe. In children we might find, as the cliché goes, a path forward into the future, away from the stasis of conjugal forms and the economic and social structures they represent. In an adult man pretending to re-enter his childhood, we find a make-believe so jarring it prevents us from suspending our disbelief even as it draws us in: we find, again, the beginning intertwined with the end.

Helen Charman’s forthcoming book is Mother State: A Political History of Motherhood (Allen Lane, 2024)