Afterglow, a multi-site exhibition across London, seems caught between idealism and contradiction – who is it all for?

A gospel choir, gymnasts and tango dancers were among the odd bedfellows Marinella Senatore gathered for the opening event – and central illuminating force – of her multi-site exhibition Afterglow. After a procession to the amphitheatre-like forecourt of Battersea Power Station – the site of a nearing-completion luxury property complex – singers, musicians and dancers did their thing, purposefully unrehearsed and to a timetable structured around overlaps: two wrestlers writhed on the ground before a choir of seniors; a steel band played David Bowie’s Life on Mars (1971); an operatic solo soared above it all. What underpinned the roster was each group’s progressive principles: the black ballet company Pointe Black for instance is a challenge to the dance-form’s elitist white history; Esprit Concrete’s parkour is therapeutic.

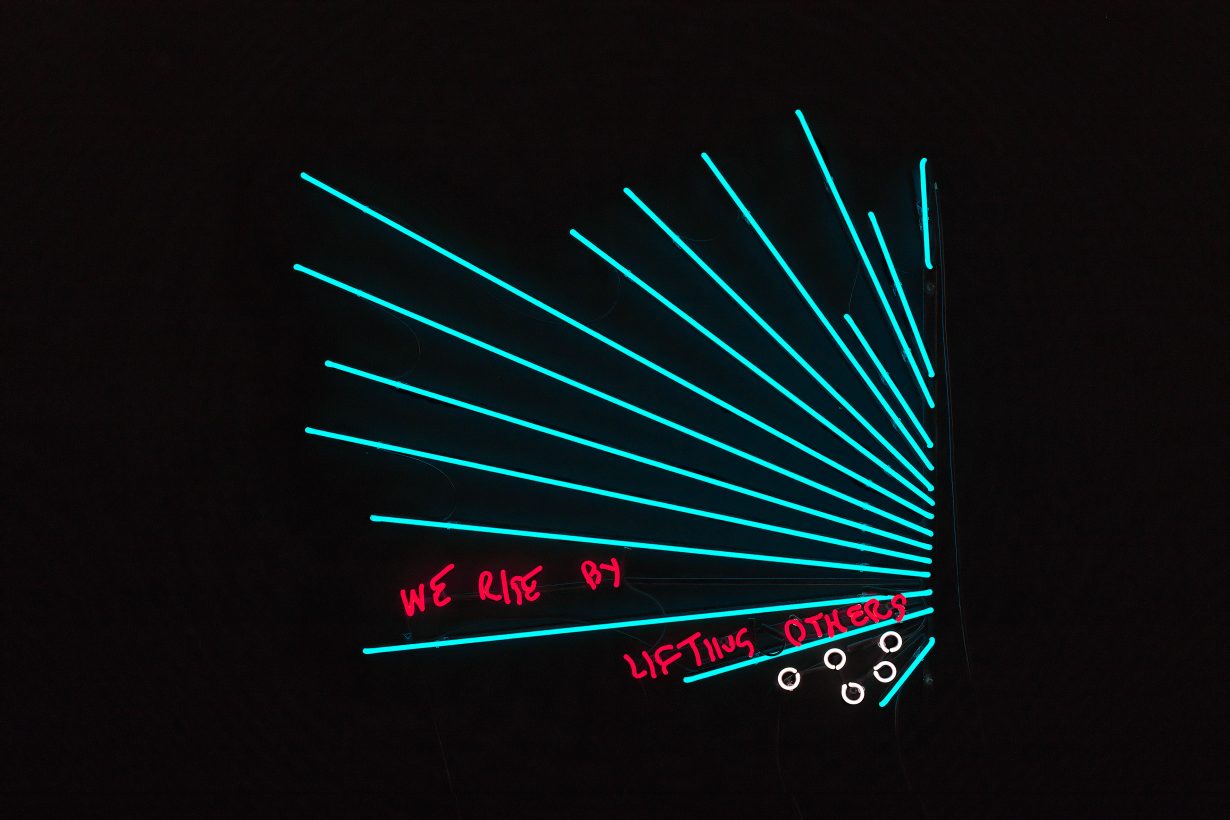

Setting the scene, one of Senatore’s signature light sculptures provided a contemporary take on Southern Italy’s traditional ‘luminaries’, which recreate outlines of baroque cathedral facades with electric lights for religious festivities through piazzas and streets. At Battersea, the words of contemporary spiritualist Jeff Brown – ‘At the heart of our expansion is the capacity to be vulnerable’ – glowed in mercury-free neon. In central London, another lightwork was installed above the entrance to the SIAL primary school, which shares a building with the British Ukrainian Association, and where, as an appendage to the opening event, schoolchildren performed an Italian Second World War-era song to show solidarity with Ukraine. Nearby, at the courtyard of swanky ethical restaurant Petersham Nurseries, diners could contemplate a lightwork espousing the nineteenth-century American agnostic Robert Ingersoll’s belief that ‘we rise by lifting others’.

Though the gallery materials highlight the dictionary definition of ‘afterglow’ – ‘a pleasant feeling remaining after a pleasurable experience’ – for Senatore both light sculptures and performances are imbued with a greater purpose: they generate energy to change ‘space’ and ‘individuals’. She’s notably pursued this idea of ‘social change’ through the ‘transformative power of collective experiences’ developed with her School of Narrative Dance, whose ten-year anniversary celebrations Afterglow kicked off.

Taken at idealistic face-value, Afterglow’s concurrent performances enacted an egalitarian community that thrives on difference, with art buffs and passersby alike potentially drawn into this brief alternative society. Senatore has previously spoken of her desire to reach a wide public, yet in staging work in economically elite locales, she seems to actively court contradictions. It’s impossible not to wonder, at one of London’s most notoriously costly developments of apartments and shops, who can an epiphanic ‘free for all’ be for? And to what end – consciousness-raising or conscience-easing? Is amplifying the illusion that a site owned by a corporate consortium is a democratic public space taking the revolution where it counts, or art-washing the privatisation of the civic landscape?

The accompanying Bond Street gallery exhibition underlines the hazy impact of live events, as well as the challenges of creating objects that might adequately convey their oomph. A low-lit room with a white sand floor nods to Fabio Mauri’s 1968 arte povera installation, Luna. Instead of awesome journeys into the cosmos, Senatore evokes the nebulous territory of inner space. Opaque coloured light boxes that quote Walt Whitman on human potential, ‘I contain multitudes’, are an invitation to wonder what might lie within. The artist’s hands, replicated in frosty peach glass, stretch upward from a plinth, seeking connection.

A second room includes a scaled-down festive lightwork with a famous misquote from Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (1952), glowing in disco violet: ‘Dance First Think Later’. In a play whose characters repeat themselves and wait, these words are often taken as a call for action. Yet a series of pencil drawings opposite suggest that Senatore is equally alive to Beckett’s imprisoning stasis. Based on photographs of global protests, they include a suffragette in 1908, a banner for Barnsley Miners’ Wives and her previous collaborators Pussy Riot. Countering Senatore’s can-do performances, this community of transhistorical activists implies an overarching futility, with people compelled to rise up again and again.

One drawing, in which Margaret Thatcher is confronted by the fashion designer Katharine Hamnett sporting one of her famed political statement T-shirts, felt telling. In this constellation of eternal struggle, Hamnett’s project underlined the dilemma that vexed Afterglow’s defining event: her T-shirts brought pressing issues into everyday conversations in a way that felt sincere but easy to dismiss, without making the powerful pay serious attention.

Afterglow at Mazzoleni Art and other venues, London, through 26 August