How the Mexican artist turned to the discipline of art history as a way of losing control

The vanguard art of the 1960s and 70s is generally thought of as cerebral, rational, systemic, self-contained. But consider that the first edict in Sol LeWitt’s 1968 manifesto ‘Sentences on Conceptual Art’ is this: ‘Conceptual artists are mystics rather than rationalists. They leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach.’ Remember that Dan Graham was really, really into astrology. Note that the brainiac progenitor of conceptual art, Marcel Duchamp, was outed in John F. Moffitt’s 2003 book Alchemist of the Avant-Garde: The Case of Marcel Duchamp as being active in alchemy and all manner of off-beam esotericism. Entertain the possibility that Bruce Nauman’s 1967 neon The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths might not be even halfway ironical. For the past two decades, it’s been part of Mario García Torres’s artistic project to crowbar open our understanding of this art-historical lineage – suggesting that stylistics such as Conceptualism, Arte Povera and institutional critique are more complex, or based on different assumptions, than widely assumed – and use such revisionism to microcosm wider complexities, obscured stories beyond known frames, hidden potentiality, unfixity.

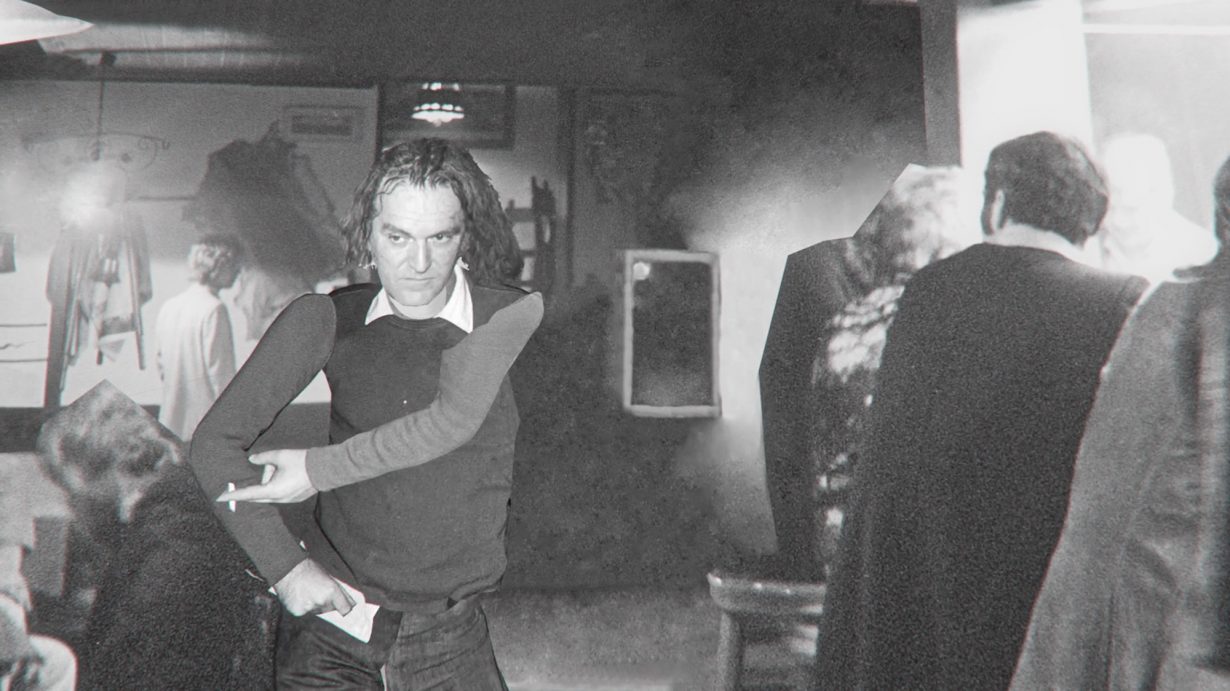

See, for example, a cornerstone work in A History of Influence, the Mexican artist’s current retrospective at Kassel’s Fridericianum: 2010’s ¿Alguna vez has visto la nieve caer? (Have You Ever Seen the Snow?). This slideshow-converted-to-video follows García Torres’s attempts to find Alighiero Boetti’s One Hotel, which the Italian artist ran in Kabul between 1971 and 1979, long thought destroyed. Through travels and archive-delving – and a bit of fictionalising – García Torres ‘finds’ evidence of its historical existence, at least. As he zooms in on photos of the alleged hotel, his eye and his voiceover catch all kinds of chance details; at one point, he even claims he’s potentially found Boetti himself, seen in reflection, photographing the frontage of his own establishment. For another work (pointedly undated, like a number of the artist’s projects, as if unhitched from linear time), Merz, Rzemmmm, Zeeeeerm, Emrzzzzzz (At Fibonacci Pace), García Torres found and animated a photo of Mario Merz in a Kassel bar that the latter frequented while installing at Documenta in 1972; in the film, the Arte Povera artist dances in said hostelry, increasingly rapidly, to banging electronic music whose rhythms – and Merz’s movements – relate to the integers in the Fibonacci sequence; Merz seems to be dancing his way towards infinity.

Ask García Torres, as I did recently by email, where this urge to dilate the past and see it as changeable and expansible comes from, and he says, appropriately enough, that what he thinks today about that is different to what he thought a decade ago. “I would have said that repeating acts was done with the faith that they were just forms, containers, whose meanings would become very different if displaced in time. Today I’d say they were ways of believing in myself, finding a way to legitimate myself as an artist, looking for like-minded people, even if they weren’t in the same time and space. I guess there’s something of transcending my condition, breaking notions of time and geography, and believing through the work I could do the impossible, like checking into Boetti’s hotel.”

One way of framing García Torres’s own ‘history of influence’, then, is that he engaged with a certain type of artist, and playfully reread and complicated them, until he became a peer. (“Nothing gives you permission to be an artist,” he notes.) Of late, his work has accordingly leaned less on historical artists, though it’s still magnetised to the recent-ish past. The (again undated) two-screen film Cayendo juntos en el tiempo (Falling Together in Time) travels back into the early 1980s via voiceover and archival footage, to tell a story that suggests an infinitude of near-mystical synchronicities – between, for example, the Van Halen song Jump (1984), the story of Muhammad Ali stopping someone from leaping off a building, the rappers House of Pain, blue-eyed-soul outfit Hall & Oates, vintage synthesisers, thinkers Carl Jung and Arthur Koestler, and a trucker stuck in a traffic jam near Manchester – rewriting the past through seemingly magical linkages. When the film ends, it feels like García Torres (or you the viewer, with a bit of effort) could go on like this forever.

In Kassel, that work sits near a series of multipanelled, silkscreened, flowchartlike canvases (2024–25) that, similarly, diagram quixotic relations within the history of music, making plenty of room for South American and Latin musicians: in García Torres’s cosmology, for instance, it’s only two steps (via a New Order sample) from Joy Division to Spanish rapper C. Tangana; disco is an important node in dance music, but so, here, are bandleaders Tito Puente and Eddie Palmieri. These diagrams, semaphoring the delivery of facts, hitch the scientific affect and outward objectivity of text-driven conceptual art to the telling of new stories, and so to a loosening of control: they don’t feel like the final word on something, more one way of organising a world, perhaps even creating a world by describing it. “A trick that the second movement of conceptual art – in the 80s and 90s – played on me, and maybe other artists, is that one had to control meaning, control our output and by doing that transmit a clear, hopefully critical message,” says García Torres. “I wanted to go exactly the opposite way, to create work where meaning was more porous, that would lead me to more uncertain places, and where the work lived in people’s minds, in misunderstandings. I started to understand that pop culture was a place where all kinds of people could coincide.”

This thinking about expanded audiences has paid off in other ways, too. Housed in a little room that you must stoop to enter (unless you’re a child), the 2012 cartoon (animated by Tomoko Hirasawa) Xoco, The Kid Who Loved Being Bored, might function as a gateway to art for kids, though García Torres says he was aiming towards “the inner child of an adult”. In it, the titular Xoco – big-eyed, expressionless and turning up elsewhere in the show as a large plush toy sometimes used in performances – discovers beauty inside boredom via his imagination (and a wavering horizon line). This work leads back to a previous presentation by García Torres in Kassel, in Documenta in 2012 – a year when he was, himself, supposed to be on sabbatical, doing nothing. If the work sounds hokey in description, in person it’s charming, a child-adapted variation on what its maker often seems to be saying: that there’s always wiggle room and possibility and difference, even or especially where there seems to be little, materially, to engage with. (Plus, the artist notes, this doing-nothing character is the opposite of the goal-driven characters we’re used to seeing in the commercial, capitalistic world.)

In a work like this, for all that it demonstrates García Torres beginning to outgrow a need to engage specific conceptual forebears, there’s a transvaluing of dematerialisation and an engagement with a hidden history of art: showing that nothing, seen through the widest lens, is really something, something spacious, endless. “I think we have been misreading conceptual art for a long time,” he affirms. “Most of those works that presented themselves as purely intellectual are very much related, I would say, to ethereal and sublime ideas. If we think of the most pure, hardcore conceptual artworks – the most immaterial – they are nothing but the acknowledgment of the existence of a nonphysical world. They in fact inhabit that world. If we think of statements where a work was a telepathic message, as with Robert Barry, or Lawrence Weiner’s statement that works need not be made, they’re only pointing to the existence of that romantic, yet disruptive vision of the world. I want to think that, more and more, my work goes in that direction,” says García Torres. A figure long adept at placing other artists’ practices on different tracks is, evidently, now doing the same for his own.

A solo exhibition of Mario García Torres’s work, A History of Influence, is on show at The Fridericianum, Kassel, through 27 July

From the May 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.