In a photographic survey of maleness, Oliver Basciano finds the focus oddly narrow

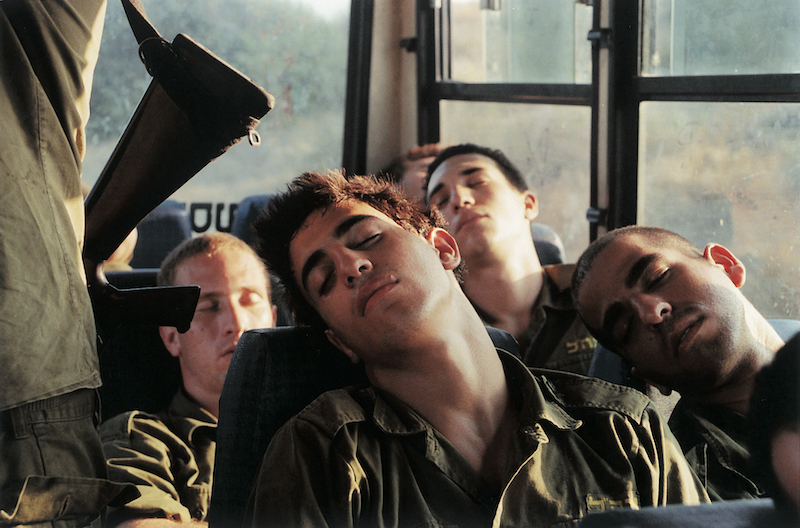

This survey exhibition is a feast for the eyes, particularly if your eyes are partial to feasting on fit men. Featuring over 300 photographs and films, both editorial and art, by more than 50 artists, the exhibition seeks to survey how masculinity has been represented from the 1960s to the present. The beauty pageant begins in military fatigues: Adi Nes’s Soldiers series (1994–2000) features youthful Israeli servicemen, seemingly caught by an embedded photographer. A narrative of barely concealed mutual homoerotic desire runs through the body language of these subjects, all unnaturally handsome. One photograph shows four of the military men peeing in a line; in another a guy is caught snoozing on an army transport bus, the lens trained on his thick, muscular neck. In a khaki tent, a soldier lying on his side, the bare soles of his feet exposed to the lens, stares across at a brother-in-arms who is messing around with a candle, dripping wax on his hand. Nes’s photos are, in fact, entirely staged. So too the rough Lebanese streetfighters shown posing and flexing on Beirut’s ruined streets in Fouad Elkoury’s series Militiamen: Portrait of a Fighter, Beirut (1980). The men, though real soldiers, are, we’re informed via a gallery caption (it’s not obvious from the photos themselves), taking part in a film.

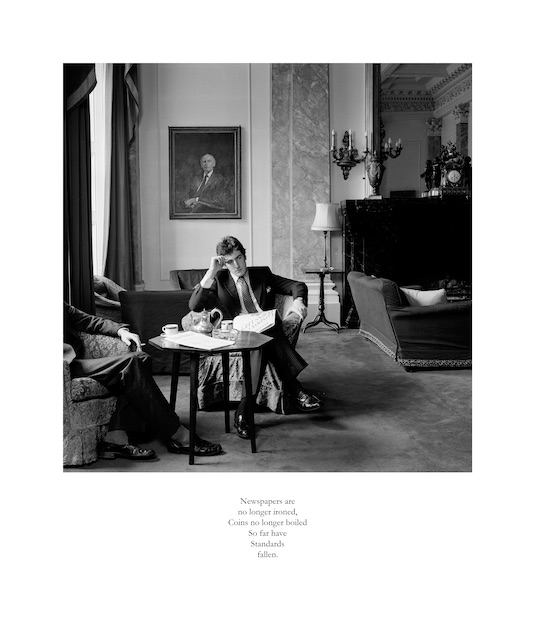

These images of the man’s ur-role – fighter and protector – provide an introduction to an exhibition that seeks, so the curatorial blurb says, to explore ‘the diverse ways masculinity has been experienced, performed, coded and socially constructed’. The problem is, as the show progresses, that diversity is not really evident. Instead what we get is an exhibition of queer erotics, almost entirely dated to the twentieth century. No bad thing in itself – there is some fantastic work here – but by approaching masculinity through this narrow gaze, the exhibition has little work addressing the toxicity of patriarchy, or the social change engendered by the #MeToo movement, both of which are reference points claimed by the curators. Barely a handful of works tackle the patriarchal order at its most potent (and potently awful). Karen Knorr’s Gentlemen (1981–83), picturing members of London’s private clubs, their privilege evident in body language as much as the stately interiors, is a rare exception. Likewise Richard Avedon’s The Family (1976), a grid of 69 portraits of America’s political, military and media establishment, almost all white and male; but these works, in this context (The Family was originally commissioned by Rolling Stone to mark the country’s bicentennial, during the first post-Watergate American presidential campaign), do little to move the conversation beyond identifying the privileged demographic. Better in this regard, and notable in that it is one of the most recent works on show, is Andrew Moisey’s The American Fraternity: An Illustrated Ritual Manual (2018), which documents jocks indulging in not-always-innocent hijinks. The works originally appeared as a photobook and were accompanied by an essay – not on show here – by Nicholas L. Syrett, an academic in gender studies, who notes that the activities depicted, ‘such as excessive drinking, hazing and womanising, can all be seen as trying to make ourselves a more masculine man’. More such interrogative insight into the insecurity of heterosexuality would have been a welcome addition to the show (recent moving-image work by artists such as Ed Atkins, Andrea Bowers and even Jordan Wolfson spring to mind).

The straight world is again addressed in a section of the exhibition dedicated to the family, but with works such as Duane Michal’s Grandpa Goes to Heaven (1989), Masahisa Fukase’s touching Memories of Father (1971–90) and Larry Sultan’s Pictures from Home (1984–92) – the last featuring Sultan’s father in his retirement village (practising his golf swing, vacuum-cleaning in his socks) – the curating here concentrates on the vulnerability of old age. Otherwise the exhibition cycles through homoerotic tropes, including the sportsman (Catherine Opie’s pictures of American high school football players, be they floppy-haired twink Devin, his hand resting on his groin, or Stephen, his toned midriff showing beneath a tiny Superman T-shirt); the bodybuilder (Robert Mapplethorpe’s photos of Arnold Schwarzenegger – all abs and oil – or Herb Ritts’s pictures of a muscled guy lifting tyres); and the cowboy (Isaac Julien’s steamy After Mazatlán, 1999/2000). All these images fall under the rubric of gay fantasies of hypermasculinity. Other galleries are dedicated to images of effeminate but no less highly sexualised men. A 1970 photo by Karlheinz Weinberger shows a long-haired dandyish type naked but for a long fur coat, his cock as thick as a cola can. Just as camp is another studio photograph by the Swiss artist in which a different model wears nothing but a straw boater and the tiniest of tiny denim shorts, the fly teasingly unzipped. The viewer peruses these pics, as well as Peter Hujar’s 1982 images of the ethereally beautiful drag performer David Brintzenhofe, soundtracked by The Paris Sisters’ 1965 version of Dream Lover, its perky doo-wop sound-spilling from Kenneth Anger’s three-minute film Kustom Kar Kommandos, made that same year. A young man, tanned, blond hair Brylcreemed back, polishes an evidently beloved hot-rod.

Some wall space is reserved for other groups outside the dominant white Western heteronormative power structure, though these too tend to intersect with queer identity. An outing for Isaac Julien’s Looking for Langston (1989) is always welcome, the 45-minute film telling the story of black gay identity via an uptown Manhattan speakeasy, segueing between the 1920s of the Harlem Renaissance and the 1980s disco scene. One character wrestles with his twin desires to “hunt dark meat in Harlem” and for “being loved”, a tension between sex and emotional connection also palpable in the quotes attached to Sunil Gupta’s photographs of gay men in New Delhi. While India’s social conservatism during the 1980s was no barrier to guys copping off in the ‘party and park scene’, it severely limited the chances of a committed relationship. Photographed with none of the exhibitionism of the European and American subjects, turning away to protect his identity, a man named Jangpura is quoted as bemoaning ‘being alone with no prospect of meeting anyone’.

Most illuminating however is a small selection of work by female artists examining the female experience of masculinity, not least Laurie Anderson’s Fully Automated Nikon (1973), photographs of men who harassed the artist in the street; and the voyeuristic pairing of Annette Messager’s The Approaches (1972), sneak pics of men’s groins, and Tracey Moffat’s Heaven (1997), snatched footage of male surfers changing, a welcome promotion of straight female erotic desire. Yet this lens on heterosexuality is all too brief; while art history has long been written by straight white guys, the urgent work is not to ignore them in exhibitions such as this, or exclusively to consider masculinity through a queer gaze. Instead the camera needs turning round to allow moments of self-interrogation.

Masculinities: Liberation through Photography, Barbican Art Gallery, London, 20 February – 17 May 2020

From the April 2020 issue of ArtReview