With David Raymond Conroy and the Friedensbibliothek/Antikriegsmuseum Berlin

Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, 4 March – 7 May

If intermingling art and activism is the topic of the moment, Andrea Büttner can claim precedence, having long examined how people act on their convictions: for example, she filmed nuns who live with a travelling fair and work in its community for the work Little Sisters: Lunapark Ostia (2012). The German artist’s latest iteration on the theme is this exhibition, which gives other voices a platform – or, to use her lexicon, a shelter. Her own works are here too, with their air of modesty: more than a dozen woodcut prints, made between 2005 and 2017 and exploring signature themes – elementary architecture in Tent (marquee) (2012) and Tent (two colours) (2012–13), holy orders in Dancing Nuns (2007) and hooded, begging figures in three works titled Beggar (2017). In these mostly one- or two-colour works, sometimes more than two metres wide and generally at least one-metre tall, subjects are limned with sharp lines carved into the wooden block and minimal detail: the supplicants, for example, are sacklike cloaked shapes, just two outstretched hands visible.

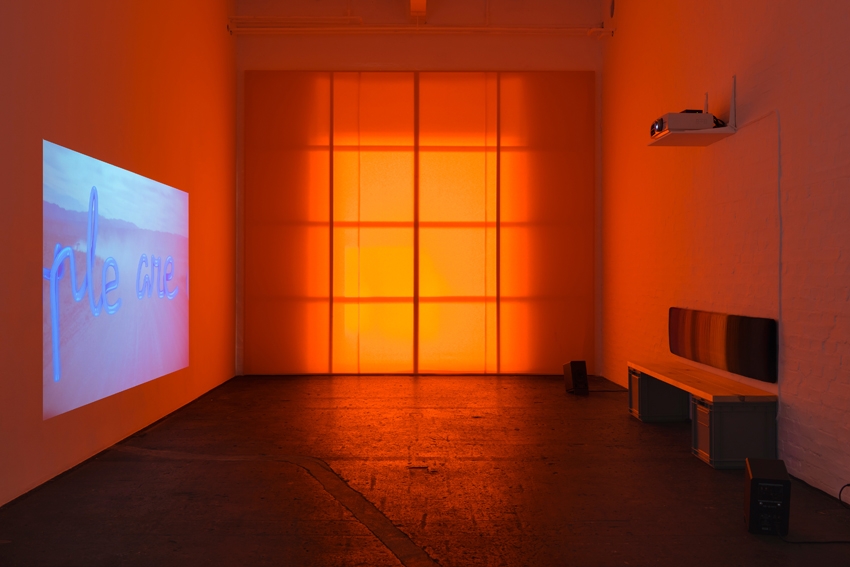

Placed centrally, however, in the Kunst Halle’s first gallery and prominently in the third is an exhibition from the Friedensbibliothek/ Antikriegsmuseum (Peace Library/Anti-War Museum) in Berlin, an institution of the Protestant Church that produces travelling educational displays. This one, mounted on rudimentary wooden stands, highlights the writing of Simone Weil, writ large on A4 sheets interspersed with A4 prints featuring familiar black-and-white images of key events from the last century. Three chapters are created in the display from quotations of Weil’s writings from the 1930s and 40s (the French philosopher and teacher died, aged just thirty-four, in 1943). The opening section, ‘The Needs of the Soul’, outlines her thoughts on the responsibilities of freedom, while ‘Uprootedness’ bemoans the influence of money, capitalism and nationalism, with August Sander images of workers, industrialists and soldiers segueing into Don McCullin, Leticia Valverdes and others who reported on war, famine and misery in Vietnam, Brazil and elsewhere. Finally, in ‘The Growing of Roots’ Weil’s words argue that good and evil must be taught and the young motivated to act, alongside pastoral and still-life images by Josef Sudek and photographic portraits of noteworthy figures. In the middle gallery, Büttner includes British artist David Raymond Conroy’s film (You (People) Are All The Same) (2016), a 40-minute handheld record of the artist’s attempts to make an artwork, his (ultimately aborted) plan being to ask a homeless person to gamble the production budget accompanying his Las Vegas residency. Conroy is stymied by events and lack of time as well as his own reservations about the dubious endeavour, his being just one of several voices recounting the events that happen off-camera over footage shot like a video diary, while the whole is tied together by another, authoritative American woman’s critique, spoken as if picking over evidence.

All three elements of the exhibition share a DIY aesthetic (and, no matter how well meant, demonstrate how easily the art market will be able to absorb this ethical candour). Each part is a scaffold sustaining something more substantial – be that literally, in the case of the Weil exhibition; Conroy’s would-be diary that weaves a complicated fabric of naivety, guile, calculation and moral judgement; and Büttner’s prints, in which the bare lines relate to systems and questions of faith or life. As conductor and author of the composition, Büttner’s bigger picture (as the exhibition title translates) consists of immense concerns about human nature, though the topic of presentation embedded within it is important too. Why, for example, does a didactic tool appear anomalous in an art institution? Is the appropriation and instrumentalisation of documentary photography in the exhibition warranted? We are more at ease watching Conroy’s video, second-guessing the sincerity of what is on display even while understanding that his questions relate to ethics. ‘Das Höchste ist nicht, das Höchste verstehen, sondern es tun’ (‘The greatest achievement is not to understand greatness but to do it’) is one of Weil’s quotations; in this context, should we interpret it as an indicator that we are too fixated on understanding when we look at art? I don’t believe Büttner wants to discredit the art space, but maybe to show that an aesthetic forum is inescapably a moral one too.

From the May 2017 issue of ArtReview