MNAC Central, Palace of Parliament, Bucharest 10 November – 26 March (Phase One)

‘The Romanian’s favourite material is wood,’ wrote the prolific Romanian artist, poet and essayist Mihai Olos (1940–2015) in a 1988 essay. From ‘the peasant’s spoon and pot’ to Constantin Brancusi’s elegiac Endless Column (1938), an early version of which was rendered in oak, wood ‘has (human) warmth and tolerance and extinction’. In the same text Olos recalls his friendship with Joseph Beuys, and the performative exchanges that followed their collaboration at Documenta 6 in 1977. Later, when Beuys created 7000 oaks (1982), Olos ‘remembered that he had asked me what wood I used most frequently to carve my sculptures in – “Oak wood”, I told him. His oaks will grow into timber for his posterity.’ The essay ends with the poet’s touch for enigma, in three seemingly disparate images that go from flight to fall; ‘I dreamt of Beuys (…) playing the violin – from a distance, with a long bow, I was playing the same violin. Then, on no violin, we played together, using only the two crossing bows. It is snowing. 4 March 1988 – a remembrance day of the sinister earthquake from Bucharest.’ In these lines there is an echo of the ‘warmth, tolerance and extinction’ that Olos recognised in wood and in humanity. The following year, the pan-Eastern Bloc revolutions of 1989 hailed a violent end to the megalomaniacal leadership of Nicolae Ceaușescu in Romania.

The Ephemerist is the title of this two-phase retrospective of Olos’s career, housed in a fraction of Ceaușescu’s obese folly, the Palace of the Parliament. A bittersweet title, referencing the code name of the surveillance files held on Olos by the secret police pre-1989, it also indicates the artist’s discursiveness. Olos rarely dated his work, but approximately 400 pieces from the late 1960s to 2000s feature in phase one (with a reshuffle for the second phase, from 27 April to 8 October, to concentrate more on drawings and documentary material). A core arrangement of tabletop knotted objects that incorporate readymades such as paper receipts, pencils and playing cards leads towards larger wood, ceramic and basketry sculptures, and paintings that range from abstraction to erotic expressionism. The display propels you around the gallery’s tiers in a fashion mirrored in the painting Sâmbra Oilor (Celebration of the Fellowship of the Sheep, undated). This is a more obviously figurative work than most here, but it perfectly exemplifies the exuberance found throughout Olos’s oeuvre.

The knot, a structure based on the intertwining of six elements found in the peasant’s home, is a motif that surfaces repeatedly. Conjuring an association with early mystic Constructivism, the infinite combinations of the knot were, for Olos, part of a utopian, philosophical strategy that would unite East and West through the transfer of sacredness from the local to the universal. Intentionally or otherwise, some paintings invoke a mental overlay of the hammer and sickle, or the swastika. Alluding to the current ‘dangerous resurrection of all sorts of nationalisms and fundamentalisms’, the exhibition’s accompanying text speaks of ‘looking without prejudice’ at how Olos’s ‘radicalism of experiment is fuelled precisely by a radical, uncompromising understanding and appreciation of the popular culture’, namely the Romanian folk traditions into which the artist was born.

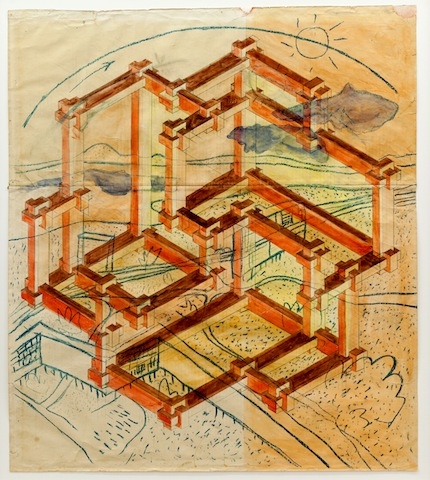

In an untitled gouache on paper from 1974, interlocking timberlike beams (again, the knot) float, disconcertingly impossible in perspective, over what appears to be a loosely drawn semi-industrialised landscape. An arching line, underscored with an arrow, shoots across a sun drawn with childlike charm. This combination of the diagrammatical and naive has a playful yet pointed effect that is as abstruse as the motion in the picture plane, and I’m reminded in this instance not of the shamanic practice of Beuys, but of the irony of Sigmar Polke and the aesthetics of ‘Capitalist Realism’. That Olos may be found at almost every juncture of late Modernism is worth the investigation this retrospective affords, but what resounds is the singular, uplifting voice of an artist whose nation bore the postwar experiment with arguably more turmoil than most.

First published in the May 2017 issue of ArtReview