The artist’s works, exhibited at London’s Freud Museum, are fraught with psychological angst

‘But nobody could climb through that pattern – it strangles so; I think that is why it has so many heads,’ says the narrator of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s 1892 short story, ‘The Yellow Wall-Paper’. Text from Gilman’s story and passages from Sigmund Freud’s case studies and Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis (1915) are included in the publication that accompanies the drawings by Ida Applebroog currently being exhibited at the Freud Museum. The American artist chose the texts herself, and we can understand why. The drawings – which she made in 1969–70 in San Diego’s Mercy Hospital, where, struck with severe depression, she interned herself for six weeks – are fraught with psychological angst, questioning what it is to be human. Of these texts, Gilman’s story bears the most direct resemblance to Applebroog’s drawings, not least for its protofeminist overtones, being about a woman’s domestic isolation as she undergoes a nervous breakdown (at the climax of which she identifies with a colony of imaginary women living within the wallpaper, trapped and trying to escape) and her subjection to her more ‘rational’ physician husband.

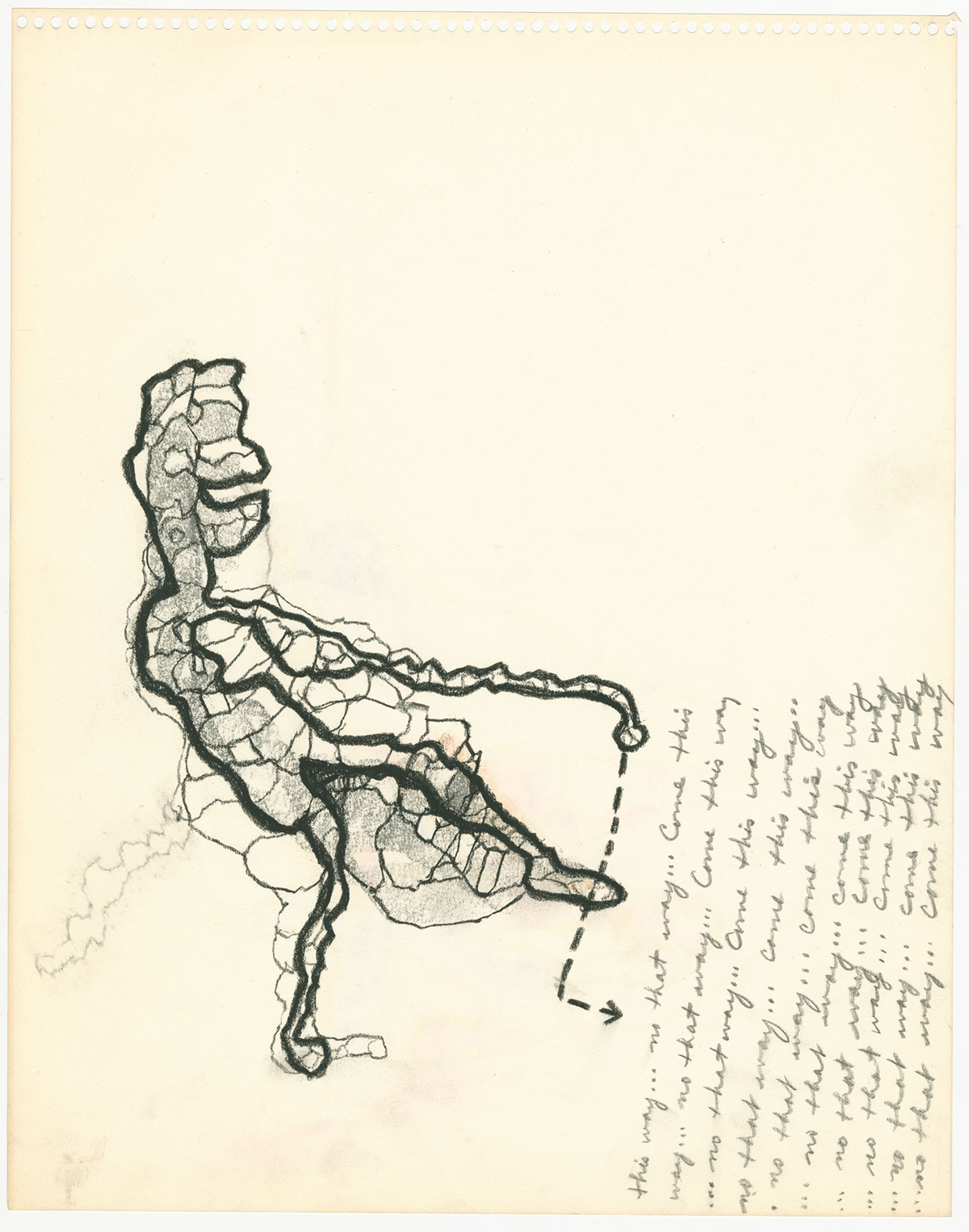

Like Gilman’s wallpaper, the drawings are inhabited by amorphous, seemingly animate forms that hover between emergence and obscuration – you can’t tell if they’re coming or going. Scribbled in the bottom corner of one such drawing are the words this way… no that way… Come this way…. no that way… repeated over and over, aligned vertically and scrawling from the bottom of the sheet to about halfway up, continuing for ten lines until she runs out of room. The last four of these lines are compressed, crammed in; we are left with the impression that if it were not for the arbitrary border of the page, she’d have carried on repeating these words forever.

To the left of this marginalia is a humanoid form jaggedly outlined in black pastel – and yet there is nothing really to signify that this is a human being or meant to be a figure at all, human, anthropomorphic, animal or otherwise. The ‘head’ is like the head of a turtle, but its ‘mouth’ could also be an estuary, just as the withered ‘breast’ could be a promontory or the ‘arm’ a peninsula. Then again, is it anything? Is it not just an abstraction? Like many of the ‘figures’ in the Mercy Hospital series, it plays on our own inclination to recognise the familiar in the strange. We automatically see a figure – I see a ragged old man with a walking stick, but there is nothing really to signify that this is what is being represented. Nor is there anything to say that the faint squiggle behind it is necessarily a tail, or an imaginary tail, or if in fact there are two figures overlapping, one the devilish alter ego of the other, and so on… In this sense, the drawings play on our own inherent madness. We are all like Gilman’s heroine to a certain degree, we all see ourselves in the pattern on the wall.

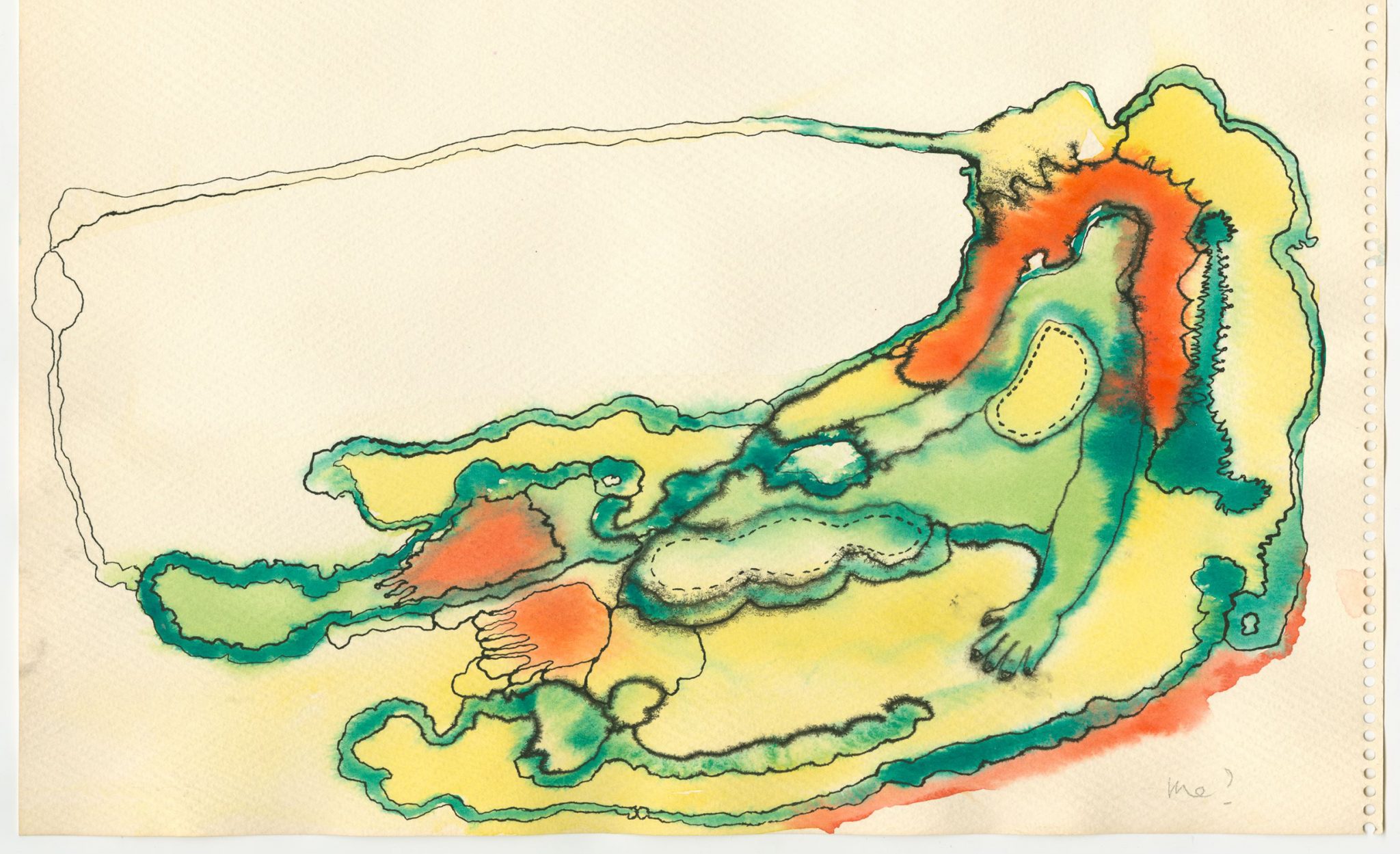

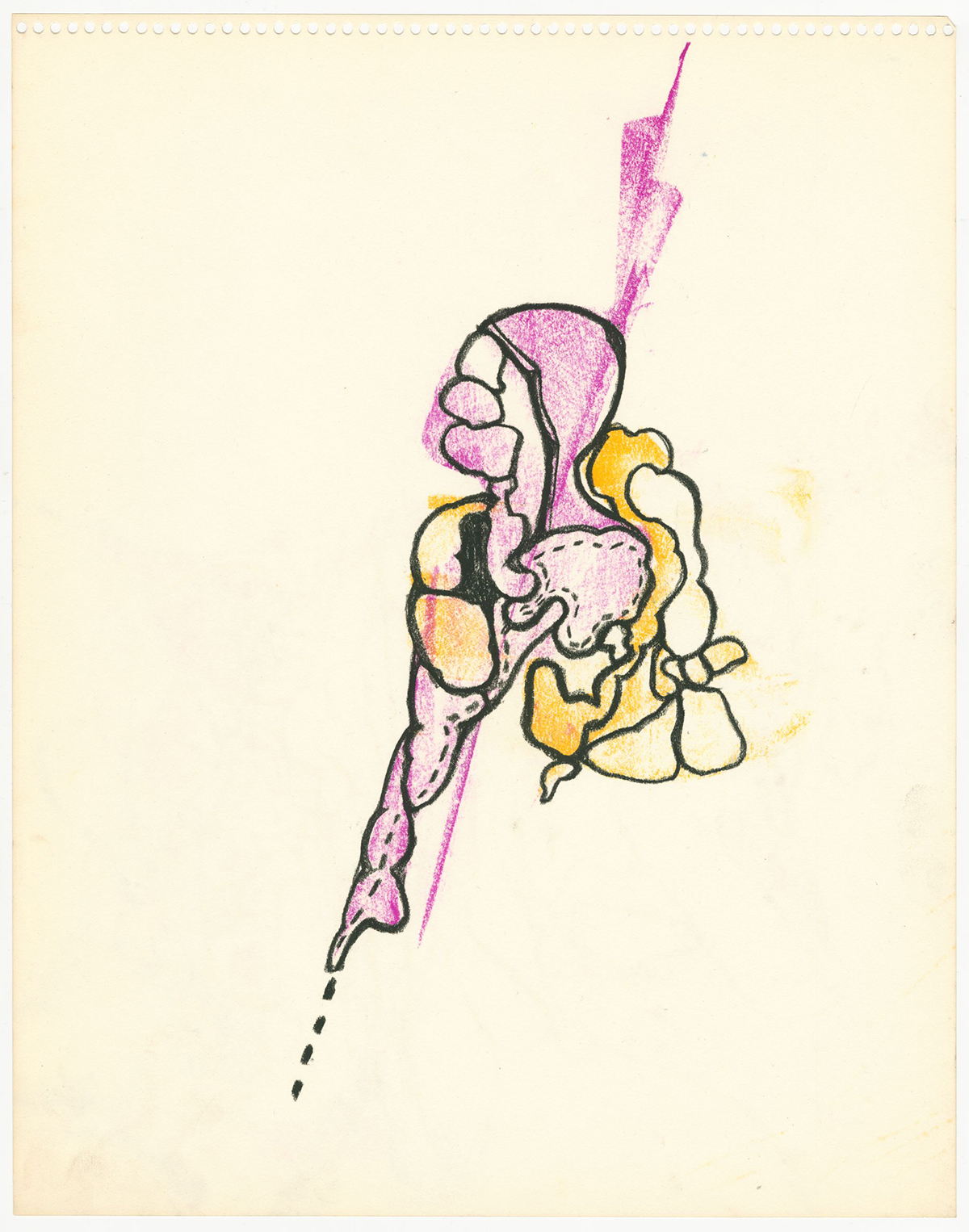

The boldness of outline, variance of linear texture and professionalism with which each line is marked (which itself is demonstrative of her training as a graphic designer), and the context of hospitalisation in which Applebroog made these drawings, lends them an organic cellularity that is no less than menacing. “I am more interested in doing something to the viewer than saying something to the viewer,” Applebroog would say later, in a documentary film made by Beth B, her daughter, in 2016. They resemble at once the cellular forms seen through a microscope and geographic formations seen macroscopically from a great height or outer space. Indeed, it cannot be ignored in the midst of pandemic that they bear an uncanny resemblance to magnified (and viral) photographic images of the coronavirus, which takes its name from the pricked, crownlike circumference of its membrane. This is especially the case in those drawings in which ‘wet’ media like ink and watercolour predominate, as the clouds of colour, and the black boundaries that seem to be trying to contain or exclude them, smudge and bleed.

At a symposium held at University College London in 2011, Applebroog talked about the years 1969 and 1970 – just after she had moved from Chicago to San Diego – as a time in which she craved sanctuary. The lines in these drawings are indeed boundaries, topographical in both the geographic and biological senses of the word. They are barriers within and outside of our bodies, which, for Applebroog – a self-described feminist who has often said that at a young age she learned ‘how power works’ – amount to the same thing. Her biology, as a woman, has proven to be restrictive, and yet the walls society has built to restrict her are not of her own body or her own will. At the same time, walls, boundaries, isolation, when it is her choice to be isolated, are conducive to introspection, sanctuary and – in the case of Mercy Hospital – recuperation.

Ida Applebroog, Mercy Hospital, at the Freud Museum, London until 7 June.