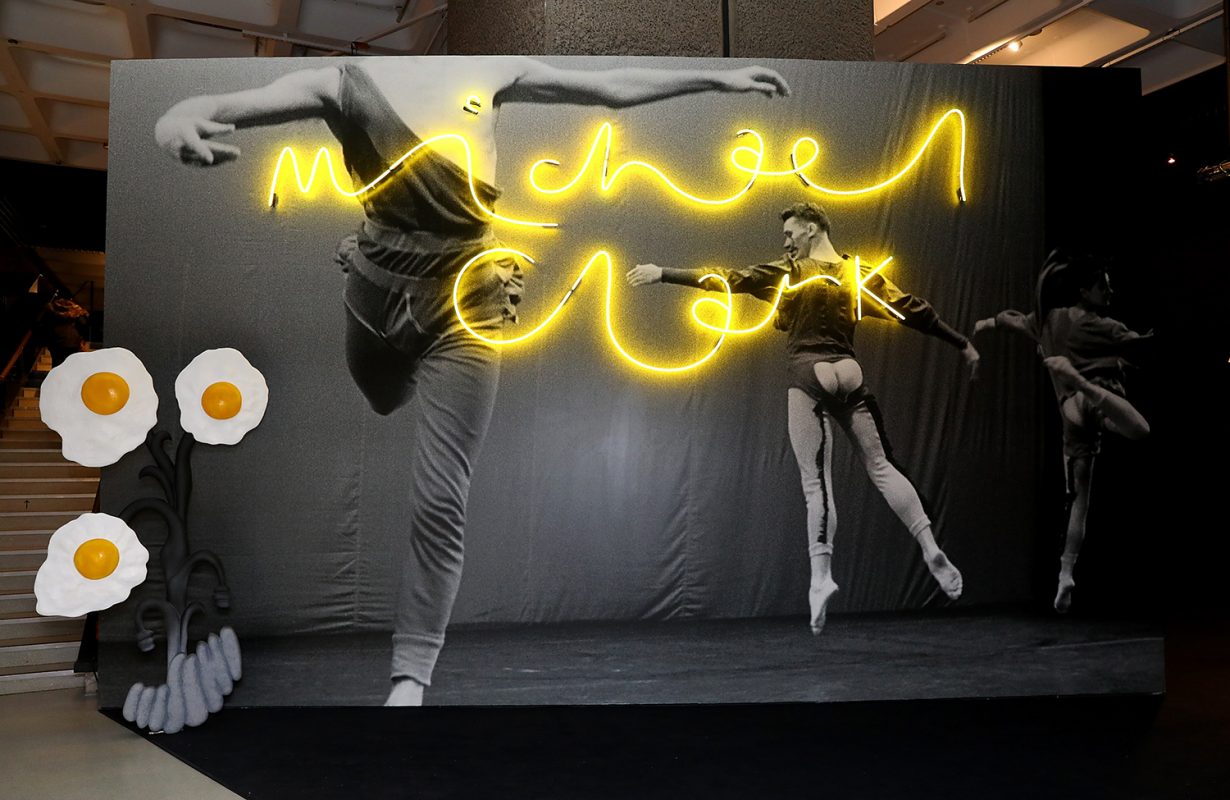

At London’s Barbican, Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer is loyal to the choreographer, and rich in its exploration of the creative scene pulsing around him

Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer at London’s Barbican continues its series of exhibitions devoted to contemporary dance, including Laurie Anderson, Trisha Brown, Gordon Matta-Clark (2011) and Trajal Harrell: Hoochie Koochie (2017). Celebrating home-grown talent with the first major exhibition of perhaps Britain’s most renowned contemporary choreographer, Cosmic Dancer is billed as a ‘constellation of portraits of Clark, through the eyes of the artists who have worked with him.’ And as risky as this approach sounds, with all its potential for platitudes and superficiality, what results is a diamond of an exhibition loyal to its subject, ambitious with its displays, and rich in its exploration of the connections between art, friendship and love.

The Barbican is a tricky exhibition space to master, its centre cavernous and echoing, impaled by gargantuan squared pillars, flanked by minor chambers and overlooked by a segmented upper mezzanine. For Cosmic Dancer its potential to disorientate has been used effectively to convey the riotous punk energy that infused Clark’s beginnings. Blacked out and sectioned off, the space is set alight by Charles Atlas’s new video installation A Prune Twin (2020) cut from two of his previous ‘docu-fantasies’, documenting exaggerated versions of Clark’s early life. Hail the New Puritan (1985–6) located Clark in a cold, bright warehouse of London’s east-end where he choreographs and rehearses alongside others (playing, in Atlas’s words, ‘outsize versions of themselves’), twirls along canals, travels on tubes, styles himself in performance artist Leigh Bowery’s dark apartment, dances in clubs, all set against a backdrop of scrap heaps, gas works, dole queues and the tightening clutch of Thatcher’s England. Atlas cut this work with sequences from Because We Must (1989), based on Clark’s eponymous ballet staged at Sadler’s Wells showing his troupe costumed like dinosaurs, their balletic phrasings punctuated with raucous interludes by Bowery and Leslie Bryant. Among them, Clark danced the ‘chosen maiden’ from Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (1913).

Costumes were bold, graphic, ungendered and often sequinned and Atlas used chroma-key technology to set their fabrics as dancers’ backgrounds, spinning and pivoting them to create dizzying visual effects. Re-edited and shown across nine hanging screens and four monitors, sequences run out of sync and chronology, set to the booming elegies of Clark’s youth, like the Velvet Underground’s ‘Venus In Furs’ (1967). As these images and sounds flood the space the effect is of navigating Clark’s memory of London during the early 1980s, giddy and bright and alive.

Atlas’s installation sets a tone but also provides a historical waypoint. He met Clark in 1982 when they were working with Karole Armitage in New York. Clark had progressed swiftly from the Royal Ballet School and Ballet Rambert to poke around postmodern dance as a bright twenty-year-old choreographer and Atlas was taken with the gait and flair of London’s young Warhol and the creative promiscuity pulsing around him, artists, designers and musicians bedding down in squats and riding high in clubs. Atlas was pivotal, positioning the emerging Clark before his lens for a Channel 4 commission, an opportunity that catapulted Clark far beyond the parameters of contemporary dance or London’s gritty art scene, and into television’s primetime. It also inaugurated a body of film and video that makes such a retrospective ‘portrait’ of a choreographer possible today, even without the scheduling of live dance.

Atlas’s efforts are complimented by a ‘Film Archive’ across two rooms, evidencing the role of television in Clark’s ascent, with the BBC, ITV and Channel 4 regularly broadcasting his pieces to mass audiences. Wrong (1989, ITV, South Bank Show), for example, was a dance performed nude by Clark and Stephen Petronio before a highly pixelated image of their naked embrace, accompanied by Josie Jones’s voice listing Tory wrongdoings. This piece was aired as the AIDS crises raged on but while the political and sensual realities of homosexuality remained largely unattended on British television, and there’s a strong sense throughout the exhibition of how Clark posed questions about gender, sexuality and equality through dance in nuanced and ever-evolving ways.

Around Atlas’s fulcrum comes a series of installations styled in different tones appropriate to Clark’s heterogenous collaborations. In an adjacent room is a projection of two music videos directed by artist Cerith Wyn Evans for The Fall, shot with multiple cameras on the set of Clark’s I Am Curious Orange (1988, Amsterdam, Holland Festival). Crowding this room are recreations of props designed by Clark for this irreverent, mutually charged performance, including outlandish body-size Heinz Beans cans with an outsize burger and chips. Nearby is a more sombre installation in a heavily draped dark room fitted with imposing Marshall speakers where current/SEE (1998) is projected, the image of Susan Stenger and her band Big Bottom (Angela Bulloch, Wyn Evans, Tom Gidley, and J. Mitch Flacko) encircling Clark on a dark stage as he dances. As we drown in the heavy bass of her sustained chord sequence, we watch Clark’s limbs bend and fold, his trunk rotating in slow, steady evolutions. A life, danced in abstraction.

Upstairs Sarah Lucas’s installation includes Cnut (2004), Clark’s body cast in raw concrete from the bust down. He’s sitting on the toilet smoking a cigarette. This sculpture is mounted upon another made of jesmonite, a giant pink ham Sandwich (2004). When Lucas made them, Clark had stepped away from choreography and was living with her, sometimes assisting in her studio, and I imagine the lone dancer sitting contemplating the body’s spoils. A neighbouring room is painted black. Along one side hangs bawdy costumes by Bowery and Body Map celebrating body diversity through careful cutting, contouring, and layering. Opposite them run a series of small-scale portraits of Clark by Elizabeth Peyton (made between 2006 and 2009), each capturing the quiet intensity of this watery-eyed boy, the far-away thoughts of a star in repose. As the noises and chords of Clark’s life spill between the objects and art made by his friends, this seems less an exhibition about one individual, or even a particular art scene, than an exposition of a life presented through its works and those that both roused and surrounded it.

Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer, Barbican, London, until 3 January 2021