Gamepieces at AGSA, Adelaide melds poetry with politics, brutality with moments of profound beauty, to stage the theatre of history on the female body

You almost sense them before you see them, as you make your way into the gallery. A pair of figures, wall-drawings of half-human, half-monsters, appear like tornadoes crashing through opposing walls.

Nalini Malani first made her Mutant drawings in 1996, for the 2nd Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, at the Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane. They were partly a response to the toxic gas leak at the Union Carbide plant in Bhopal in 1984, which killed more than 20,000 people. At AGSA these depictions of ecological disaster register as both epic and visceral. Half a million survivors suffered ailments including respiratory problems and blindness. One of the drawings, titled Mutant II (1996), conceals the trace of a woman; a chalk outline like a murder scene on a pavement. A ghost life that never was.

Malani was born in 1946 in Karachi a year before Partition carved up the subcontinent. Her best work reveals the female body as a stage that enacts the theatre of history. It’s a thread that recurs across Gamepieces, which features over 30 works, most drawn from AGSA’s own collection. This is the first time the gallery has devoted a solo exhibition to a South Asian artist; a radical move in a landscape of Australian art institutions that extols the ‘blockbuster’. Exhibitions dedicated to female-identifying artists are often described in the celebratory language of empowerment-feminism, but it’s still all-too-rare for a national institution to devote a major retrospective to a woman artist of colour. This despite the fact that nearly a third of Australia’s population is overseas-born, with India the fastest-growing migrant group behind the United Kingdom and New Zealand.

Gamepieces unfolds in a series of darkened rooms in AGSA’s lower-level gallery. To descend the staircase is to surrender to Can You Hear Me? (2018–20). This suite of 88 stop-motion animations, finger-drawn by the artist on her iPad, are blown up and projected across four walls. They respond to the death of an eight-year-old girl, murdered by eight men in Kashmir in 2018. Lines squiggle and squirm. They morph into faces. A girl jumps over her skipping rope. Text dissolves, the words of literary greats – James Baldwin, Milan Kundera and Rainer Maria Rilke – as disposable as a newsfeed. It is poignant within an Australian context, because while conversations and awareness around gender-based violence have evolved since #MeToo, when a woman of colour is assaulted or killed she rarely dents the national imagination.

One of the strengths of Gamepieces is the way it positions Malani as fiercely internationalist – aesthetically and politically. I’m transfixed by Dream Houses I (1969): the film alludes to Josef Albers’s colour theory and the Indian modernist architect Charles Correa. It conjures the city as a flickering grid of blue and red and green.

There’s nothing novel about erasing the divide between the East and West. But in the context of Gamepieces, this framing is oddly powerful. It shows the viewer, who may be tempted to exonerate themselves from gender politics as it plays out in ‘developing countries’, that they are part of a single visual unconscious. Gamepieces imagines this as a swirling universe of images and references that we all draw on to make meaning. It exists without boundaries: geographical, physical, temporal.

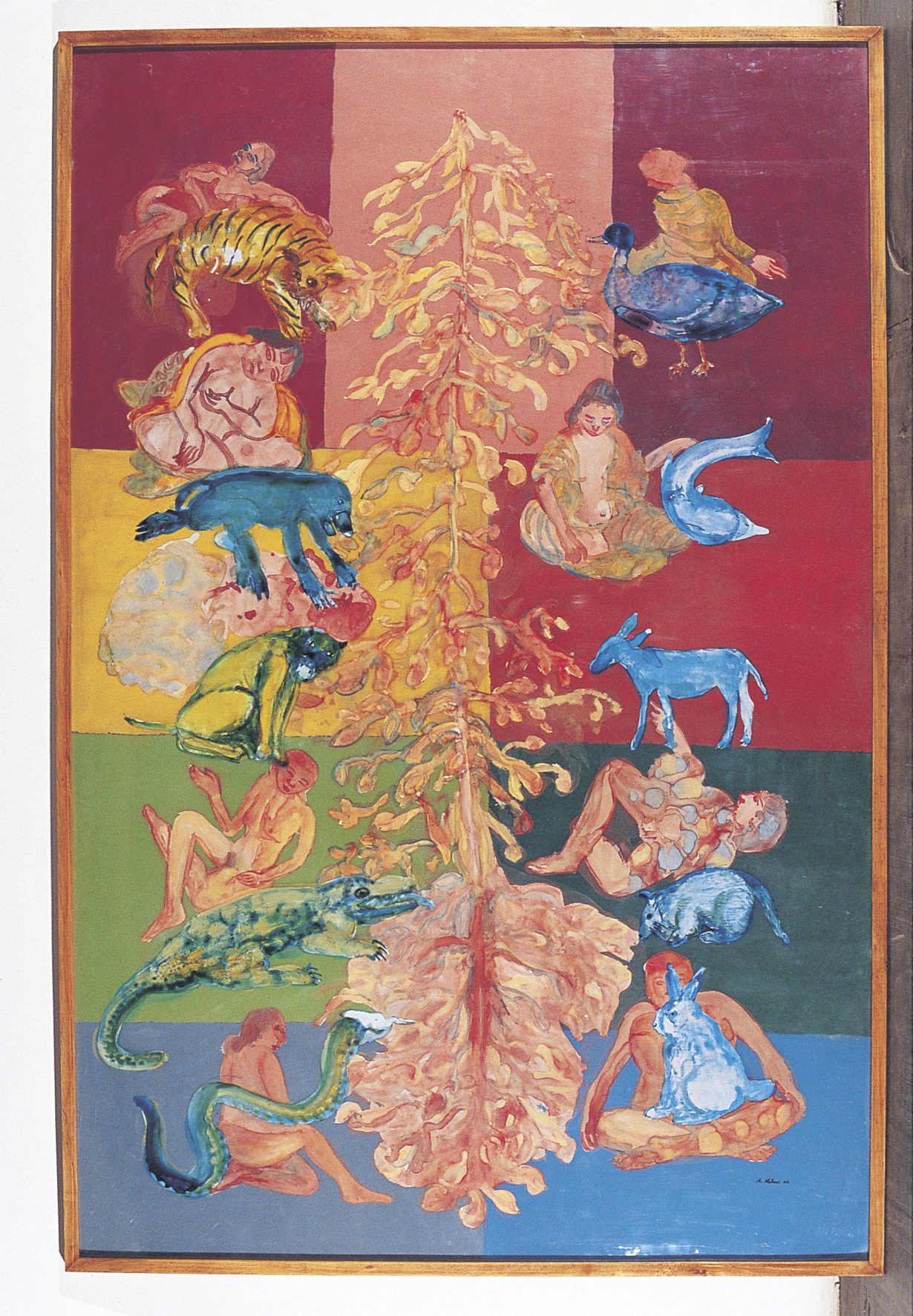

A 2002 series of paintings, Stories Retold, gives voice to the forgotten women of Hindu mythology and subverts the morality stories contained in the Bhagavata Purana. In the text, the goddess Radha is Krishna’s older, married lover, but her erotic devotion is sanitised in contemporary India. In a painting from Stories Retold titled The Ecstasy of Radha, the goddess, rendered in lush oranges and reds, embodies a spectrum of sensual pleasure. She levitates, soars and floats, at ease in her own body.

The work, which unfolds on mylar using ‘reverse painting’ – a Byzantine technique embraced by Indian artists in the mid-nineteenth century – hints at the way myths inflect the everyday. It also invites the viewer to reflect on how their biases can shape different interpretations of the same story. Archetypes, like headlines, shape our reality. They haunt our subconscious, determine how we treat each other.

Unity in Diversity, created in 2003, references the Gujarat riots between Hindus and Muslims that erupted the year before. The installation occupies a gallery that resembles a middle-class Indian living room. On one wall hangs a series of paintings, done in Kalighat, a style conceived by painters in nineteenth-century Calcutta, from the gallery’s collection. In one of these, Saraswati, the goddess of art and music, is depicted in delicate watercolour. The feminine ideal she embodies clashes with the sound of gunshots emanating from a videowork installed on another wall.

In the titular series, Gamepieces (2003–20), projected silhouettes on spinning mylar cylinders – a fish, a dragon, a girl – dance and glide through the space; in the background plays khyal, a form of Hindu classical music that stems from the Persian word for imagination. Malani’s work melds poetry with politics, brutality with moments of profound beauty. Here, she finds an equilibrium between opposing forces, a strange and shifting shadow-reality where we can dream the world again.

Gamepieces at Art Gallery of South Australia – AGSA, Adelaide, through 22 January