The artist introduces satirical sharpness and an acute awareness of the digital world in works that question the exclusionist hierarchies of contemporary art

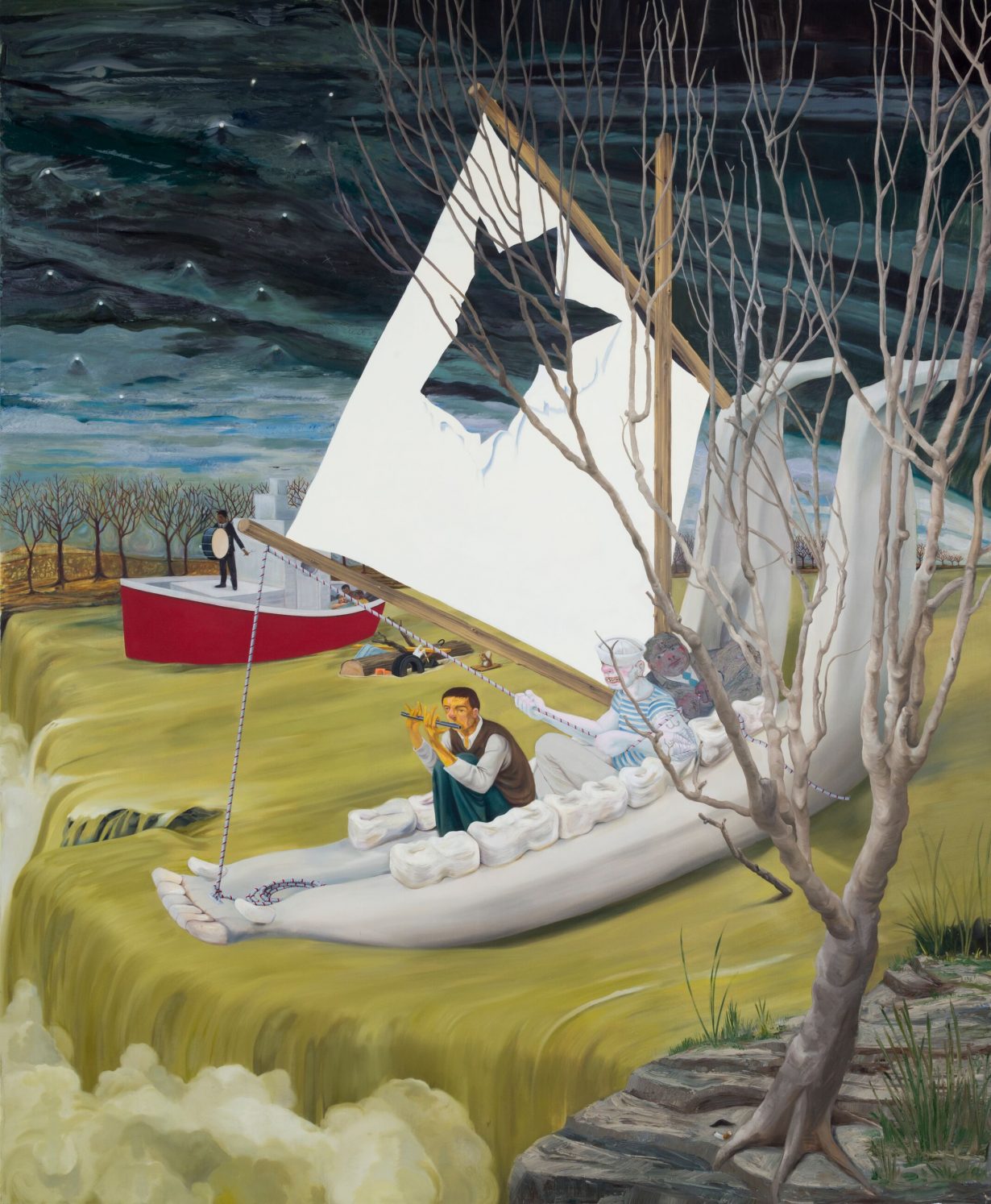

What Happened at Museum Brandhorst, Munich, begins with Heading Down River on the USS J-Bone of an Ass (2017). This painting, of a mandiblelike vessel sailing dangerously close to sending its all-male crew over a waterfall, is an appropriately scabrous starting-point for this show, with its roughly 100 works drawn from three decades of the American artist’s predominantly painterly practice and embedded social commentary. (That said, Eisenman’s latter-day recognition as a significant sculptor is attested to by the presence of Procession, 2019, a multifigure sculpture staging an ambiguous parade or protest, originally shown at that year’s controversy-shadowed Whitney Biennial and, in the present context, a kind of mysterious backdrop.) The paintings, shown across multiple rooms, are loosely organised into categories: ‘Heads’, ‘Being an Artist’, ‘Coping’, ‘Against the Grain’, ‘Protest & Procession’, ‘In Search of Fun and Danger’ and ‘Screens, Sex & Solitude’. This last focuses on Eisenman’s ongoing, decade-long pictorial engagement with present-day communication gadgets: projectors, laptops, drones, iPhones, etc. That viewers are going to photograph the work, and publish it on social media, seems factored into the artist’s reflexive thinking.

Regardless of the familiarity of the canvases for long-term Eisenman watchers, or her general offer of the pleasures of connoisseurship to viewers who can recognise the respective aesthetic epochs and styles of twentieth-century painting upon which she draws, there are a multitude of individual details in each that captivate and invite analysis. For example, in The Session (2008) it’s the dirty feet of the analysand, the arrangement of books and a phallic vase in the psychiatrist’s office, and the way the Bumble Bee fish cans and the gold ingots are stacked as a precaution against a future apocalypse – plus the cheap patriotic teacups and apathetic expressions of a dreary, prepper bunker-community – in Tea Party (2011). Or the hesitant increase in symbolic concessions to gender diversity within the framework of Jewish ceremonial meals in Seder (2010) represented by the addition of an orange to the Seder plate, which commemorates the often marginalised contributions of women and LGBTQ-identified members of the Jewish community. Or the evergreen dominance of economic market hierarchies in Commerce Feeds Creativity (2004), with its bowler-hatted male force-feeding a bound, androgyne female artist. Or The Drawing Class (2011), which burlesques figure-drawing classes by presenting the portrayers in realist detail but the nude model as a rough blob, like a badly drawn figure.

That Eisenman possessed this ease in changing styles and precision in motifs between retro-modernist high and popular surreal low-brow from the outset, and could ally it to a fine knowledge of visual tricks (eg letting the viewers believe they see and know more than those portrayed) and their deliberate use, is evidenced by early largescale works such as Lemonade Stand (1994), which addresses the capitalist initiation rite of children selling lemonade in the USA, and Swimmers in the Lap Lane (1995), which portrays swimmers straying from their lanes. Elsewhere, an installation-style collection of explicit painted and drawn depictions of lesbian (sex) utopias, hopes, empowerment, stereotype reversals and reflections of daily life in the New York artistic-activist queer milieu during the early 1990s, as well as the restaging of the multipart mixed-media wall installation Pagan Guggenheim (1994), sketch out a few perceptible moments in Eisenman’s early, scuffling period of becoming an artist in an era when painting was considered ‘outmoded’.

Indeed, Eisenman first gained attention through site-specific wall works, one of which, Self-Portrait with Exploded Whitney, from 1995 and shown at that year’s Whitney Biennial, serves as the starting point for What Happened: The Movie (2023), the video animation shown in Munich, realised jointly with Ryan McNamara, and with a voice cameo by Hardy Hill. This new work, in its satirical sharpness and biting analysis of exclusionist ways of artworld speaking and how the milieu creates hierarchies, sets to rest any suspicion that the artist might be going soft, or suspending her moral conscience, and has a decanonising effect. When you leave the show – particularly if you then tour the institution’s collection – its afterglow can still be felt.

What Happened at Museum Brandhorst, Munich, through 10 September