The artist’s early works stand in stark difference to the sombre conceptualism that followed

Early Works, an exhibition of four figurative paintings by On Kawara dating from 1955–56, is a surprise given these works’ relative underexposure, their stark difference from the Japanese artist’s better-known practice and their outright strangeness. Irregularly shaped canvases that woozily bend and distort the classical rectangle, they are strikingly expressive in contrast to the sombre conceptual ‘date paintings’ that Kawara began a decade later (another exhibition, Date Paintings, is simultaneously on display at David Zwirner’s London gallery and co-organised by the artist’s One Million Years Foundation). Early Works details a period relatively undocumented in the artist’s life; little would one guess that they were executed by a twentysomething On Kawara in Tokyo. In a thick-lined, cartoonish, almost illustrative style, the canvases allude to psychological trauma and disorder, capsuling the zeitgeist of postwar Japan. They offer a portal to a world that Kawara would soon leave behind – during the late 1950s, he moved first to Mexico and later New York – and they’ve rarely been shown, much less studied. Given that Kawara actively oversaw the dissemination of his work while alive, one is left to speculate if he himself blocked the showing of his early works until after his death.

In Early Works, Kawara’s wonky supports work in the service of apparent content, delivering a claustrophobic, hemming effect, reinforced by his use of tilted planes and eerie, mysterious subjects. Hard to interpret at first, Flood (1955) – inspired, documentation asserts, by the Kyushu flood of June 1953 – suggests a collapsing dark-green thatched roof, swarmed by ants and replete with blue-black crisscrossing twiglike forms. Invertebrates also dominate Golden Home (1956), climbing the legs and feet of a golden-hued table and stool on which sits a pile of gift-wrapped packages, and squirming over an overturned, fallen pot. Both canvases use dense patterning combined with perspectival disorientation to harness a sense of invasion and malaise.

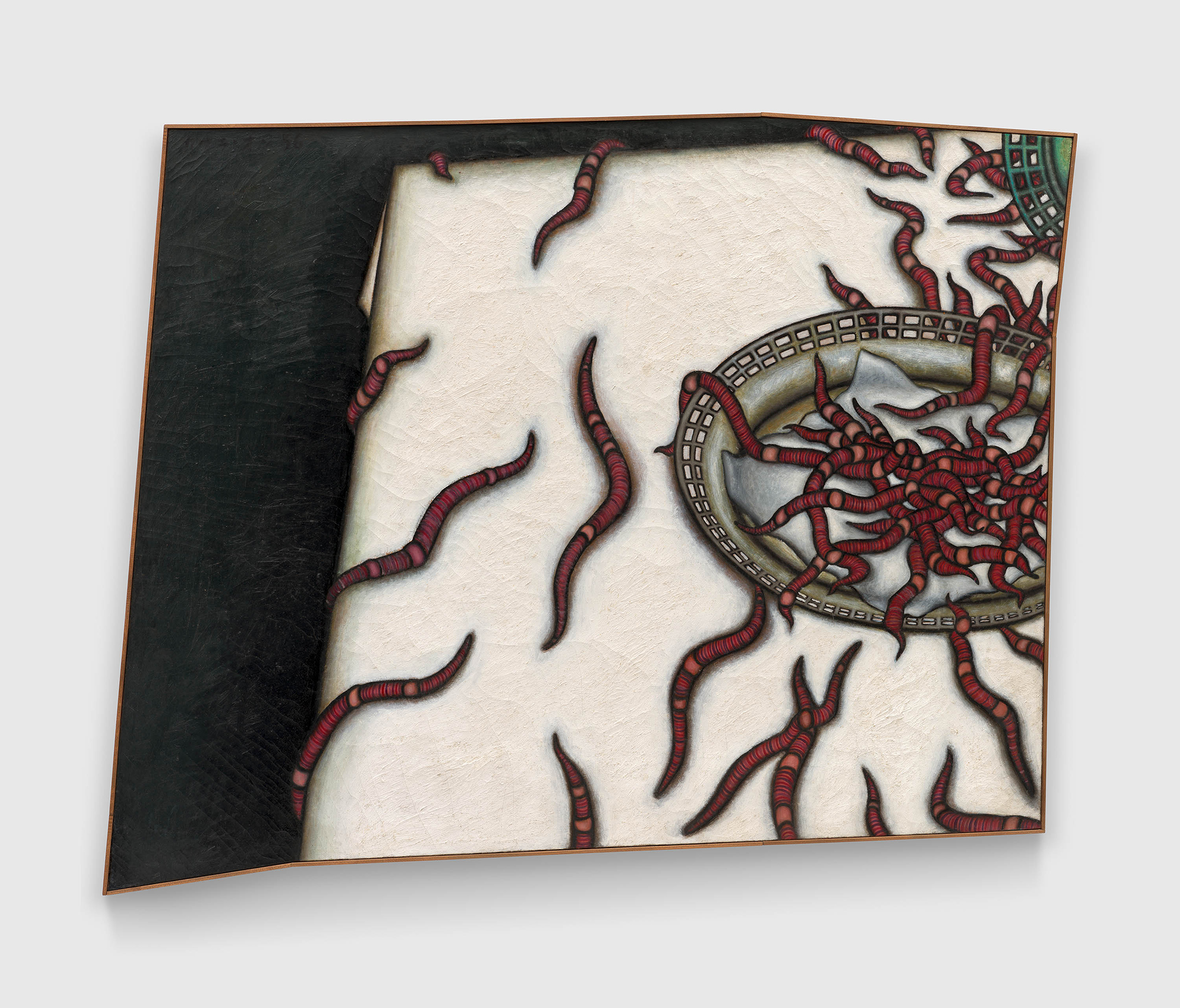

Kawara would go on to make nearly 3,000 ‘date paintings’, each attesting to moments in history and the inexorable passage of time. These concerns seem preempted by these early works, which share a sense of oblique signalling as well as a painting’s ability to convey hidden information. Untitled (1956) shows bloodred and pink segmented worms inching across a table dressed in a pristine white tablecloth, attacking two plates devoid of food. Almost a still life, the composition is structured by the worms’ writhing forms, counterbalanced by the black abyss at the painting’s left edge. Absentees (1956), meanwhile, features another unruly, teeming crowd: figures rioting in a jail cell. The appearance of their strong arms and fists, emerging from a mass of red shirts, through the grey textured walls and barred openings, screams rage in a raw gesture of nonconformity.

Though Kawara was reluctant to apply political meanings to his work, these artworks feel like social protest. And, indeed, in 1956 he stated, “I did not share the nostalgia that middle-aged cohorts had for the past. Instead, I was filled with a desperate desire to tear things apart.” True to that intent, these dreamlike Early Works translate the strange and ominous effects of history and temporal change into something immediately palpable: a trait that would carry over, in a far more elusive and less expressive manner, to Kawara’s signature works.

Early Works at David Zwirner, Paris, 23 November – 25 January

From the March 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.