Lucy McKenzie at Cabinet Gallery

3 October – 7 December (opening 28 September, 7–9pm)

Lucy McKenzie’s work seems like an appropriate way to kick off a week of unsettling juxtapositions. Whether pastiching Hergé in her drawings or art nouveau in her paintings, installing trompe l’oeil radiators in the Tate or, as the press release for this show promises, exploring ‘the fruitful exchange between retail display / mannequins and fine art’, McKenzie’s cross-disciplinary experiments seem guided by the same kind of dream logic that now binds Old Masters, performances, ‘projects’, historical avant-gardes, luxury commercialism and revolutionary rhetoric into a single, loosely associated, citywide art fair. A show taking the fashion mannequin as a starting point should be a fitting addition to a corpus characterised by a combination of apparently cold-eyed detachment – in its magpie appropriation -– and emotional charge generated by the attachment of fraught meanings to those objects and images. Expect illusionism and ambiguity, double entendres and non-sequiturs, repression and desire: what better primer for the days to come?

Wang Wei: Listen at Edouard Malingue Gallery Project Space

Through 3 November

When you get tired of the air kissing and people-watching during Frieze week, you could do a lot worse than visit this installation by Beijing-based conceptual artist Wang Wei. The work, a glowing white box, is housed in a former church and later artist studio space in Islington, now converted into a six-month pop-up space by Hong Kong- and Shanghai-based Edouard Malingue Gallery. Wei was part of the ‘Post-Sense Sensibility’ movement that organised a series of unscripted, performative exhibitions in China around the turn of the century and specialises in subtle interventions that alter the perception and interaction of audiences and their environment. At St Saviour’s his box sits in front of the altar and houses a person, visible only by their occasional silhouette, who appears to interact with the audience around them (the box is constructed such that the performer can see what is outside, even as they themselves are little more than an impression to those looking in). Who’s interacting with whom, and whether or not anyone is really interacting with anyone, become the questions of the day. Like in the art fair, but better.

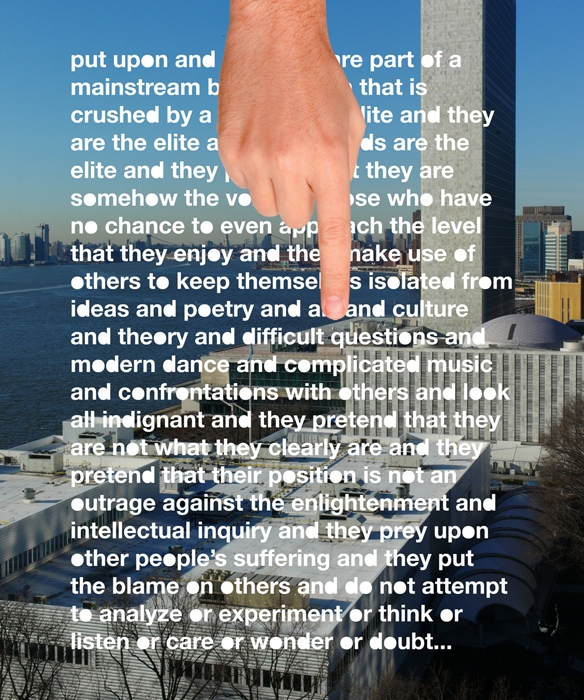

Liam Gillick, The Night of Red and Gold at Maureen Paley

29 September (5.30pm) – 17 November

Liam Gillick’s exhibition takes its name from a fictional, must-attend nightclub event described in French philosopher Gilles Châtelet’s wonderfully titled To Live and Think Like Pigs: The Incitement of Envy and Boredom in Market Economies (1998). You might want to stop right there and order the book, and look forward to a day or two of intense reading, but resist that urge (save it for your next bout of jetsetting) and push on to the show. Châtelet’s nightclub scene, which describes the emergence of a new social order (characterised by boredom, imitation, cowardice and envy – yes, back to the fair again), provides the inspiration for a new series of forms (with titles such as Festive Self Regulation and Resentment Industry, both 2019) that reflect on and further abstract the various structures that have been deployed by Gillick in his works over the years. These are further complemented by a series of films, while the show as a whole is offered as a meditation on the possibilities for ‘cultural production and workplace aesthetics’ in our porcine present, presumably populated by what Châtelet describes as the ‘gardeners of the creative’ or their descendants. Prepare to contemplate the differences (or lack of them) between free, forced and pseudo exchange: more preparation for the anxious week ahead.

Liz Deschenes: Keystone at Campoli Presti

29 September (6pm) – 17 November

Liz Deschenes’s photography-based work is ripe with references, evoking in turn the illusionism of a Bridget Riley or the rigorous sculpture of minimalists such as Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt. But the analogies quickly fade as you look closer: the vibrant pattern of her moiré prints (a photogram exposed to light through perforated paper) feel less studies into optical deception than conceptual reflections on the representation of one surface on another; while the texture of her minimalist reflective photograms defy the industrial, authorless finish of minimalism, bearing the marks of time, chance and the artist’s hand (made without a camera, a photogram results from the exposure of photo-sensitive paper to light and other elements, continuing to oxidise and evolve as it ages). For her London show, which gathers ‘keystone’ works spanning 1995 to now, the New York-based artist is pushing her explorations of an artwork’s relationship to time – and the relative evolution of its value – even further: throughout the duration of the show, the artist will rehang the works on two occasions, the exhibition itself becoming subject to change. ArtReview doesn’t want to tell you when is best to visit, for it thinks the element of chance is what keeps things from becoming desperately predictable…

Graham Ellard and Stephen Johnstone: Fossil at Weston Studio, Royal Academy of Arts

Through 6 November

Graham Ellard and Stephen Johnstone are not the first artists to turn their attention to the Royal Academy’s extensive collection of plaster casts. Beating them by a couple of centuries was Johann Zoffany. His 1780 oil on canvas The Antique School of the Royal Academy at New Somerset House shows a class of learned types sketching the educational aids in a dimly lit room of the RA’s old (then brand new) home. Ellard and Johnstone’s new film homes in on the architectural casts, made from moulds taken directly from the great architectural facades and interiors of Ancient Rome, which since the academy stopped teaching architecture in the 1950s were hidden behind temporary walls. Light has long played an important role in the filmmakers’ work, and like Zoffany before them, the precarious process of removing the casts, by hand and through various rope-and-pulley systems, is caught on 16mm black-and-white film, with an occasional eerie colour filter, as an ethereal cascade of shadows. The result, like much of the duo’s work, promises to be mesmerising.

Online exclusive, 27 September 2019