The first image in Mauro Restiffe’s 2016 monograph depicts a rectangular pond in the corner of a patiolike space. Ivy cascades down the adjoining wall, its ends brushing the water’s black surface. The image is taken with the same highly sensitive black-and-white film stock that lends a grainy quality to so many of the Brazilian artist’s photographs. This ‘black mirror’ – resembling an abyss, at once mysterious and mundane – serves as the perfect introduction to Restiffe’s relationship with the passage of time, memory and selfhood. Flicking through this publication is like strolling in unknown lands: there is no chronology or thematic division, no text at all beyond a discreet insert with the images’ captions. There are only the ‘slices of time’ that have been framed and then arranged by the artist on the page . The construction of narrative is, in large part, left to the reader.

Restiffe displayed photographs of his own family for the first time in a museum show in 2017. This exhibition at Estação Pinacoteca, titled Album, displayed two parallel lines of 73 photographs dating from 1996 to 2017 around the walls of the main gallery, ordered chronologically and reproduced in different sizes. Images of family trips, the birth of his children and domestic scenes with friends were hung with no space between the frames – with no punctuation in the sentence, if you like – such that this description of the passage of time was breathless . The lives of the strangers portrayed in scenes so familiar and intimate –a child in a garden on a summer’s day toddling towards the camera, family members and a dog only half in the frame two kids and a woman in the backseat of a car, all of whom ignore the camera’s presence – made it easy to identify with Restiffe’s biography.

These exercises in display and the creation of narrative have been a constant in Restiffe’s exhibitions since Recurrences at Fortes Vilaça in 2010. With Album the artist took it one step further, inserting paintings from the Pinacoteca’s collection (as well as from Museu de Arte de São Paulo) into these arrangements: strangers painted in oils and period dress intermingling with photographs of the artist’s inner circle. For all their intimacy, there’s also a universality to these scenes, the artist seems to be implying. Elsewhere in the exhibition – and in his work in general – Restiffe’s subject matter is less personal, the artist turning his lens to political events, architecture and street scenes. In this case, by choosing to arrange his domestic photographs by chronology – a typological strictness we might more normally associate with photojournalism, instead of the more random assemblage of the family photo album or hoard – Restiffe plays with the distinction between ‘public’ and ‘private’ photography.

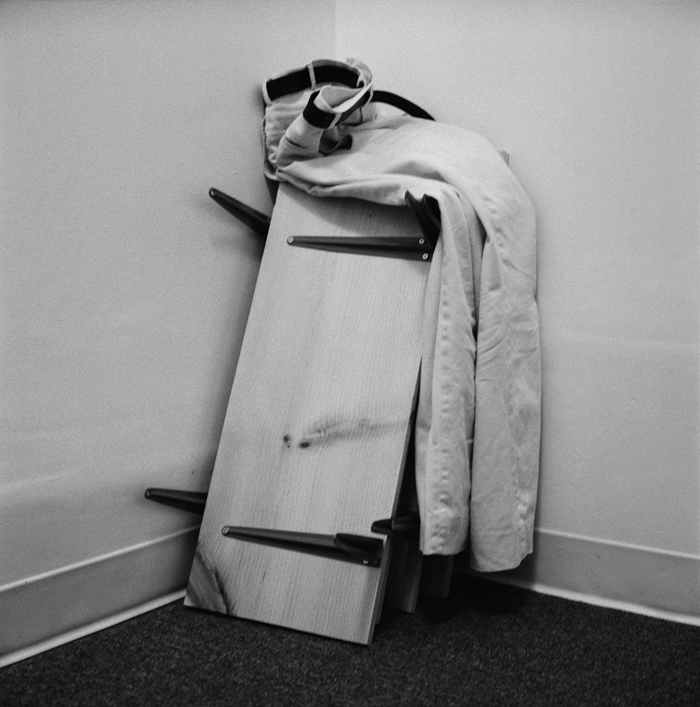

The aforementioned patio image was taken in 2010 at the house-museum of the late architect Luis Barragán in Mexico City, where photography is banned. That Restiffe’s image is evidence of a small infraction, a single hurried take, reveals something of the artist’s process. He always carries his Leica, and is prone to interrupt a sentence with the phrase “hold on, I’ve just seen a photo here,” before pulling his camera out for a quick click. Images of major political events, such as Lula da Silva’s inauguration as president of Brazil in 2003, appear alongside portraits of family and friends; travel pictures alongside architectural shots. In Empossamento #9 (2003) crowds have gathered to greet Lula, yet the back of a man’s head dominates the foreground of the photograph. In Oscar #20a (2012) five metal crosses form an improvised security barrier, turning the imposing modernist ramp in Planalto Palace into a symbolic graveyard to its architect Oscar Niemayer, whose funeral was happening at the same time. Restiffe appears in some of his photos, reflected in glass or mirrors. This reflexive approach extends to the inclusion in photographs of works by other artists. In Dutch Landscape (1997), for example, Restiffe concentrates on the wires that hold up a Vermeer masterpiece in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, making the painting look as mundane as the t-shirt reproducing The Birth of Venus (1484–86) which hangs from a clothesline in Botticelli (1995). His peculiar angles and the absence of colour brings our attention to the settings in which the paintings are installed; their physical, pragmatic presence is emphasised over their historical importance.

Nor does Restiffe eschew the documentary, journalistic possibilities of the camera. His photos at times recall the politically engagement and meditative reflection of Paul Strand’s travel records. The series Tlatelolco (2010), for example, traces Restiffe’s walk through the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Mexico City where, among numerous other historic incidents of violence, 350 students were murdered by the police in 1968. The 23 images in this visual essay register the coexistence of pre-Hispanic, Hispanic and modern Mexico in the square, and are experienced like a slow-motion film. His use of light and shadow imbues these scenes with drama, hinting, in otherwise casual street scenes, at the history of the place. While Tlatelolco has a clear political motive, series such as Europa more closely recall the candid street photography of Lee Friedlander, the product of the artist’s wandering through urban landscapes without clear purpose. The everyday and the historical combine in shots of Oscar Niemeyer’s funeral in Brasília and in another series from Barack Obama’s 2009 inauguration (Inauguração). Restiffe resists the obvious, avoiding picturesque and privileged angles, and instead turns his lens backstage and to the unremarkable corners that can reveal more about the life of a nation than any monumental imagery.

As much was made clear by Post-Soviet Russia 1995/2015 (2016), a solo exhibition at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow. In one 1996 work, Restiffe has photographed a bust of Lenin, on a high pedestal in what looks like an imposing public building, from behind. In Framed Lenin, photographed 19 years later, a small bust of the Soviet Union’s first leader occupies the alcove of a crumbling wall among disposable coffee cups, empty bottles and exposed pipework: two iPhones, one of them sharing a socket with a kettle, locate the image in today’s Russia, where Lenin now competes with consumer electronics for space. In the time elapsed between the shots the symbolic charge of Lenin’s image has diminished: in the first the viewer is looking up to the leader, in the second he has been shifted to the background, forgotten among the detritus of contemporary life. In the Moscow exhibition, this temporal and ideological shift was communicated through the juxtaposition of images taken during his two stays in Russia. If photography’s quintessential purpose is to capture Cartier-Bresson’s ‘decisive moment’, then Restiffe has not shied away from it. Yet his images have the texture of sedimented time, transmitting a sensation of duration. There is also a sense of the internal, reflexive time, that sits contrary to Cartier-Bresson, over which these photographs were taken: two decades in the life of the photographer mapped onto changes in the post-Soviet world.

When I visited the artist in his home, he shows me a photograph from 2010, titled Lab Mirrors, in which two prints, each depicting mirrors, dry in a darkroom. The images are yet to be fully exposed. Likewise, Restiffe’s quiet photography asks us to wait for the sediments to settle, and for memories to emerge.

São Paulo, fora de alcance, a solo exhibition of Mauro Restiffe’s work is on show at Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo, through 26 August