Museums now cower from anything that (they imagine) will bring them more negative publicity

The backlash over the postponement of the touring exhibition Philip Guston Now is the latest, starkest example of how museums are becoming little more than sites of social and political contestation. The show’s first incarnation, at London’s Tate Modern, had been due to open early next year. Now the show, rethought, reimagined and redone is not projected to go on view until 2024 – ‘until a time’, according to the directors of the four institutions involved (Washington’s National Gallery of Art (NGA), the Tate, the Museum of Fine Arts Houston and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) ‘at which we think that the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the center of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted’.

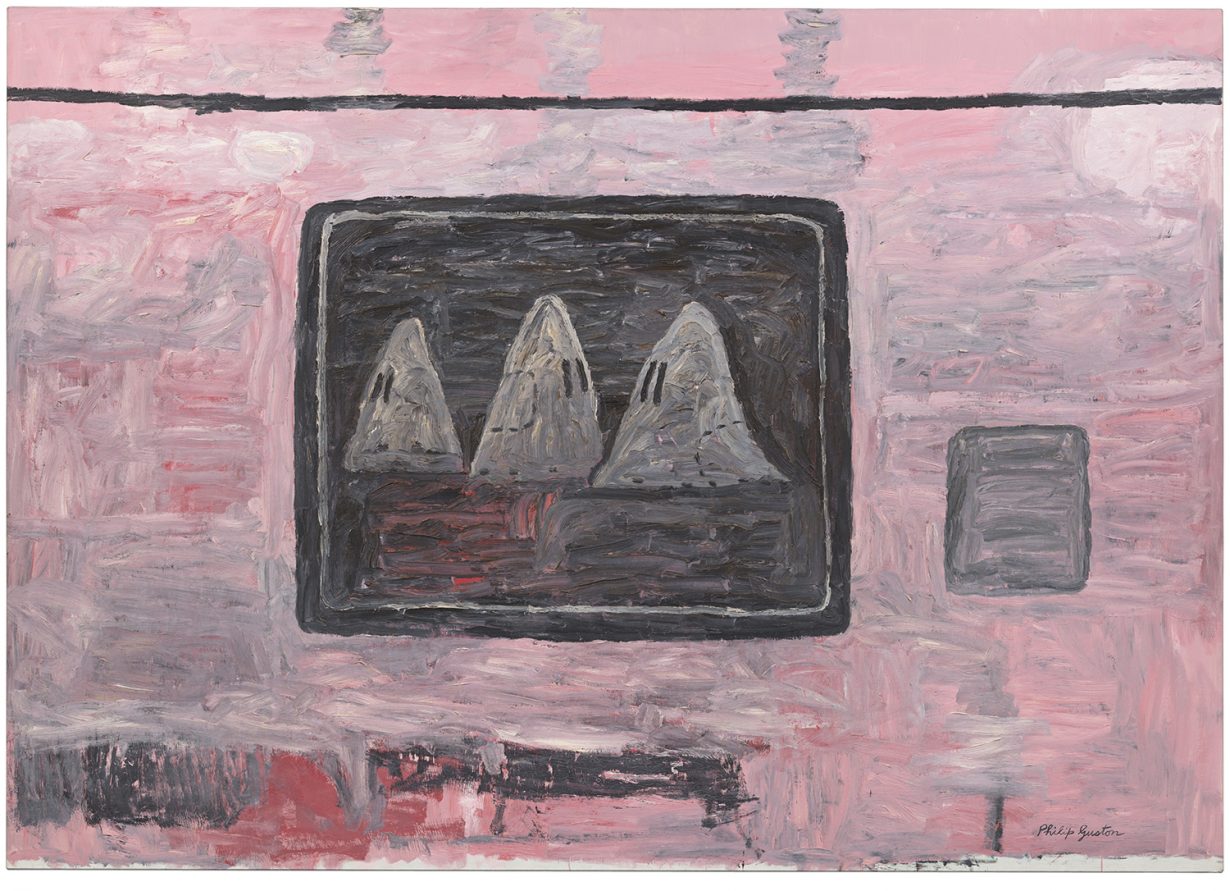

In the strange debate that has played out following this panicked decision, commentators have rushed to reassert Guston’s political credentials, both as someone who had experienced ethnic persecution himself and fought against racism in his work, arguing that his paintings of the cartoonish, white-hooded figures of Ku Klux Klansmen that the artist made at the end of the 1960s should be seen, not hidden, precisely because of their relevance to the politics of anti-racism in 2020.

What has transpired, however, is a disingenuous debate over who gets to determine what political need takes priority in determining whether art gets shown at all. Citing comments made by an NGA spokesperson, ArtNews reported that ‘organizers raised concerns over ‘painful’ imagery including the recurring Ku Klux Klan characters that appear in Guston’s late-period works’. Darren Walker, president of the hugely wealthy philanthropic Ford Foundation (and influential board member of the NGA) was even more blunt about the motives for the decision. In a statement to The New York Times, Walker retorted that ‘what those who criticise this decision do not understand […] is that in the past few months the context in the US has fundamentally, profoundly changed on issues of incendiary and toxic racial imagery in art, regardless of the virtue or intention of the artist who created it.’

However wrongheaded it is to argue that the intention of an artist, or the historical context in which their work was created, counts for nothing over whether it might offend the assumed sensitivities of contemporary audiences, Walker’s anxious reasoning is understandable: for anyone who has been paying any attention since the controversy that engulfed the 2017 Whitney Biennial’s showing of Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket (2016), the idea that images of racial violence might be offensive or even hurtful has become an integral part of the culture wars being fought over what artworks can and cannot be shown in museums, and how they should be ‘interpreted’. In this, Walker is only following this fast-forming cultural orthodoxy, in which museums have become ultra-sensitised to detecting and removing any potential cause for outrage.

© The Estate of Philip Guston; courtesy Hauser & Wirth, Private Collection; photograph: Genevieve Hanson

Yet what has been striking about the general response to this is the derision with which this argument has been met. Rather than applaud the museums for their sensitivity to audiences, commentators have advanced an exaggerated defence of Guston’s politically ‘woke’ credentials. ‘If the National Gallery of Art,’ curator Robert Storr fumed, ‘cannot explain to those who protect the work on view that the artist who made it was on the side of racial equality, no wonder they caved to misunderstanding in Trump times.’ Similarly, Mark Godfrey, the Tate curator responsible for the show’s London iteration, has gone public with his misgivings about the decision, highlighting that Guston (who changed his name from Goldstein in the 1930s) was ‘a teenage leftist from a poor Jewish migrant family that had fled anti-Semitic oppression in Russia’. In other words, Guston knew about social injustice, and whose side he was on, and his work has a political message relevant to today.

Meanwhile, others have pointed to the further validation of Guston’s work by contemporary black artists, rebuking the directors’ plea for a pause on the grounds that ‘we feel it is necessary to […] bring in additional perspectives and voices to shape how we present Guston’s work to our public’. Ben Luke, writing in The Art Newspaper, notes the contributions to the exhibition’s catalogue essays by artists Trenton Doyle Hancock and Glenn Ligon – the latter concludes that ’Guston’s ‘hood’ paintings, with their ambiguous narratives and incendiary subject matter, are not asleep – they’re woke’.

What is disingenuous, however, is how critics have sidelined the museums’ concern for audiences in favour of banging the drum for Guston, the enduringly-relevant critic of white supremacy. In a hyperbole-filled open letter, published by The Brooklyn Rail, hundreds of artists, curators and critics allege that the museums’ decision is motored by ‘white guilt’:

‘Rarely has there been a better illustration of ‘white’ culpability than in these powerful men and women’s apparent feeling of powerlessness to explain to their public the true power of an artist’s work – its capacity to prompt its viewers, and the artist too, to troubling reflection and self-examination. But the people who run our great institutions do not want trouble. They fear controversy. They lack faith in the intelligence of their audience. And they realize that to remind museum-goers of white supremacy today is not only to speak to them about the past, or events somewhere else.’

The signatories are right that ‘great institutions do not want trouble’; but it is sheer hypocrisy – one could say even moral gaslighting – to pretend one has no responsibility for this current state of affairs. After all, what these commentators seem reluctant to acknowledge is that this capitulation is not a one-off, nor is it simply an act of extreme but understandable oversensitivity to the immediate present. This has been years in the making, as contemporary critics have increasingly defined as ‘problematic’ the continued presentation of artworks made in another place and time, or the presentation of contemporary work that offends the narrowing criteria determined by an increasingly mainstream form of identity politics.

In this battle over what museums show, even rich and powerful institutions have largely beaten a retreat in the face of unceasing criticism of their failure to live up to the political and ethical demands of their critics; first over sponsorship, then over governance, and lastly over under-representation and the lack of diversity in museum programmes and staffing. At every turn, museums have shown themselves guilt-ridden and apologetic for their institutional shortcomings – promising always to do better, yet never succeeding. With each apology and retreat, museums have further emboldened their critics to dictate even more how institutions should behave, what they should show, and how they should show it.

With the open letter, those critical of the museums’ decision are confident enough to tell them what to do, and why. ‘We demand that Philip Guston Now be restored to the museums’ schedules,’ the letter declares, ‘and that their staffs prepare themselves to engage with a public that might well be curious about why a painter – ever self-critical and a standard-bearer for freedom – was compelled to use such imagery.’

But in draping themselves in Guston’s reputation as a ‘standard-bearer for freedom’, these signatories, and others who choose to hype Guston’s supposedly fearless political radicalism, are being opportunistic. In truth, the case for Guston as a strongly political artist is complicated. As an example of the vulnerabilities and compromises of an artist’s encounter with their political reality, Guston is an ambiguous and all-too-human figure: a young Jewish artist who, cleaving to the communist left of the 1930s, tracked the socialist realist figuration of artists such as Diego Rivera, Guston turned, like many of his generation, to abstraction as the political climate in the US turned violently against the left, as McCarthyism hunted down communists and socialists and the last thing an artist wanted to be seen as was ‘un-American’.

© The Estate of Philip Guston; courtesy Hauser & Wirth, Private Collection

Meanwhile, the man who Anglo-Saxonised his name from ‘Goldstein’ to ‘Guston’ to allay the anxieties of his future in-laws at a time of rising anti-Semitism in the US, does not sit easily as the emblem of a self-critical ‘white’ artist of white supremacy. Guston’s America was, after all, the one in which Ivy League colleges enforced quota limits for Jews and where, in 1944, President Roosevelt could still chide his (Jewish) treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau with the observation, ‘You know this is a Protestant country, and the Catholics and Jews are here under sufferance.’

So when Godfrey asks, ‘can we locate [Guston’s] allyship also in his act of self-scrutiny when he considered how he was implicated in White supremacy?’, he risks erasing the reality of Guston’s own Jewish experience of WASP anti-semitism, while reading the current critical preoccupations of a monolithic ‘whiteness’ backwards onto a time when the concept of undifferentiated whiteness had barely taken shape. Guston’s late return to politicised figuration, in the midst of the tumult of the civil-rights and anti-Vietnam War movements, seems more like an artist encouraged to change by the general tide of political events, rather than an unstinting assertion of his own political freedom.

But failing to oppose the tide of events is also what these museums are doing in postponing the show. The strange ‘woke’ cultural orthodoxy that has emerged in the last few years is not McCarthyism, but it is still one in which any person or any institution asserting a different perspective on current conflicts over race, or gender – or for that matter any issue of serious disagreement in the new culture wars – will likely find themselves facing sustained outrage and censure. Punch-drunk from their failure to justify themselves institutionally and culturally, museums now fight shy of anything that (they imagine) will bring them more negative publicity. Rather than face that possibility, the institutions have chosen to absent themselves while they ‘reframe’.

And yet, museums are damned if they do, and damned if they don’t. As many have noted, the three years to 2024 seem like an implausibly long time in which to reframe a show. But it is not the Guston show that will likely be reframed. It is the art institutions themselves: there are now potentially three years for new boards of trustees to be appointed; for directors and curators to be replaced; for mission statements to be rewritten; and for programmes to be torn up to make way for art whose ‘interpretation’ will not fall foul of the new orthodoxy.