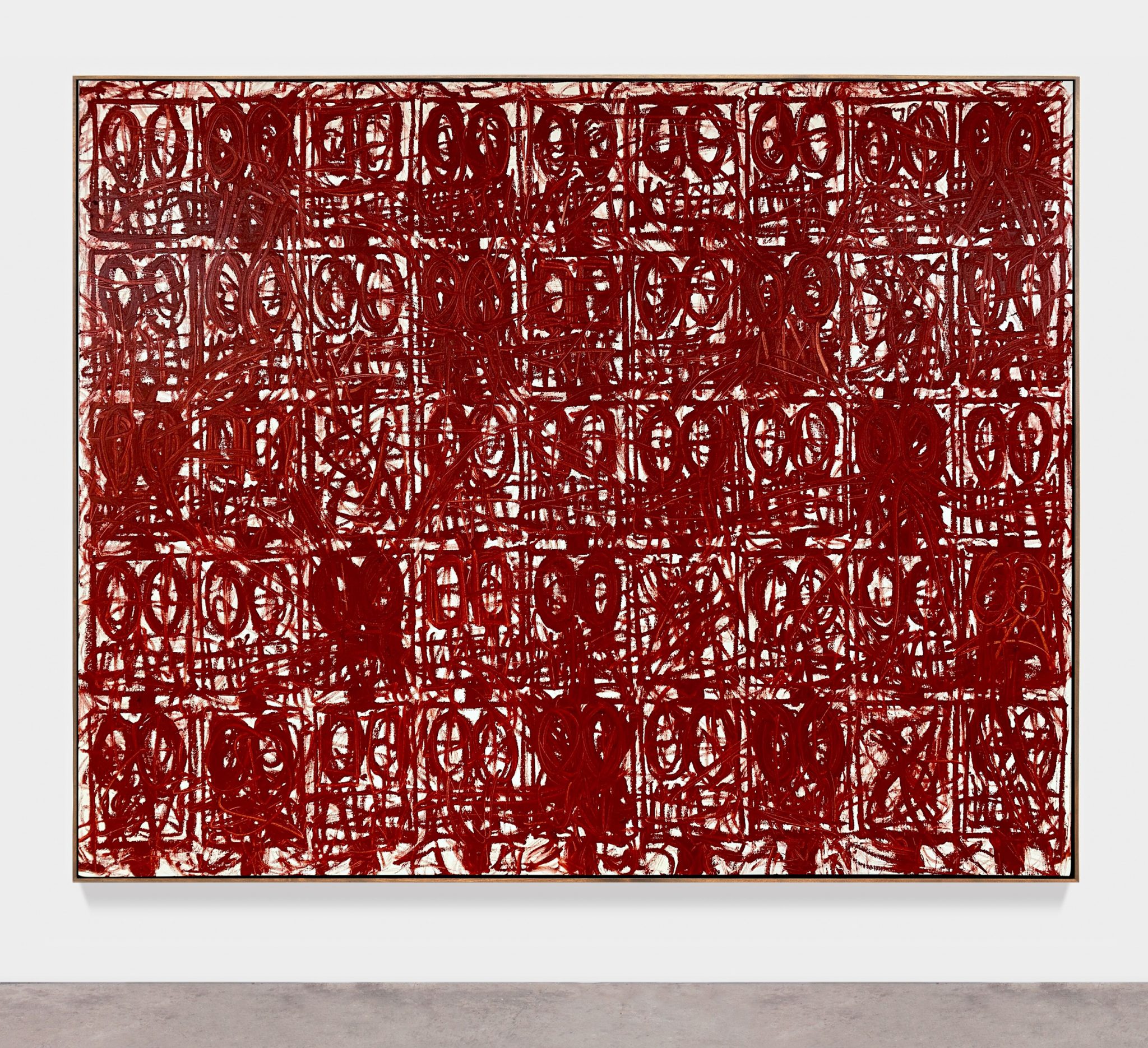

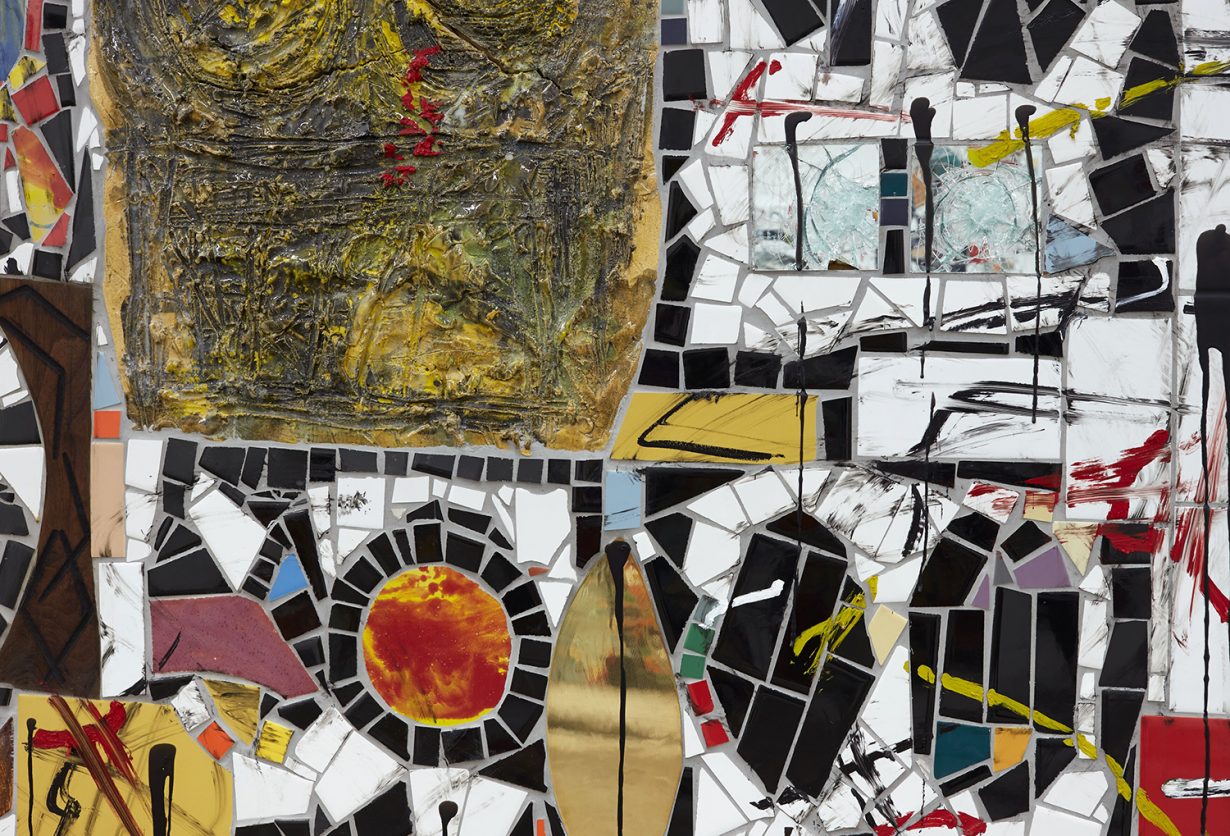

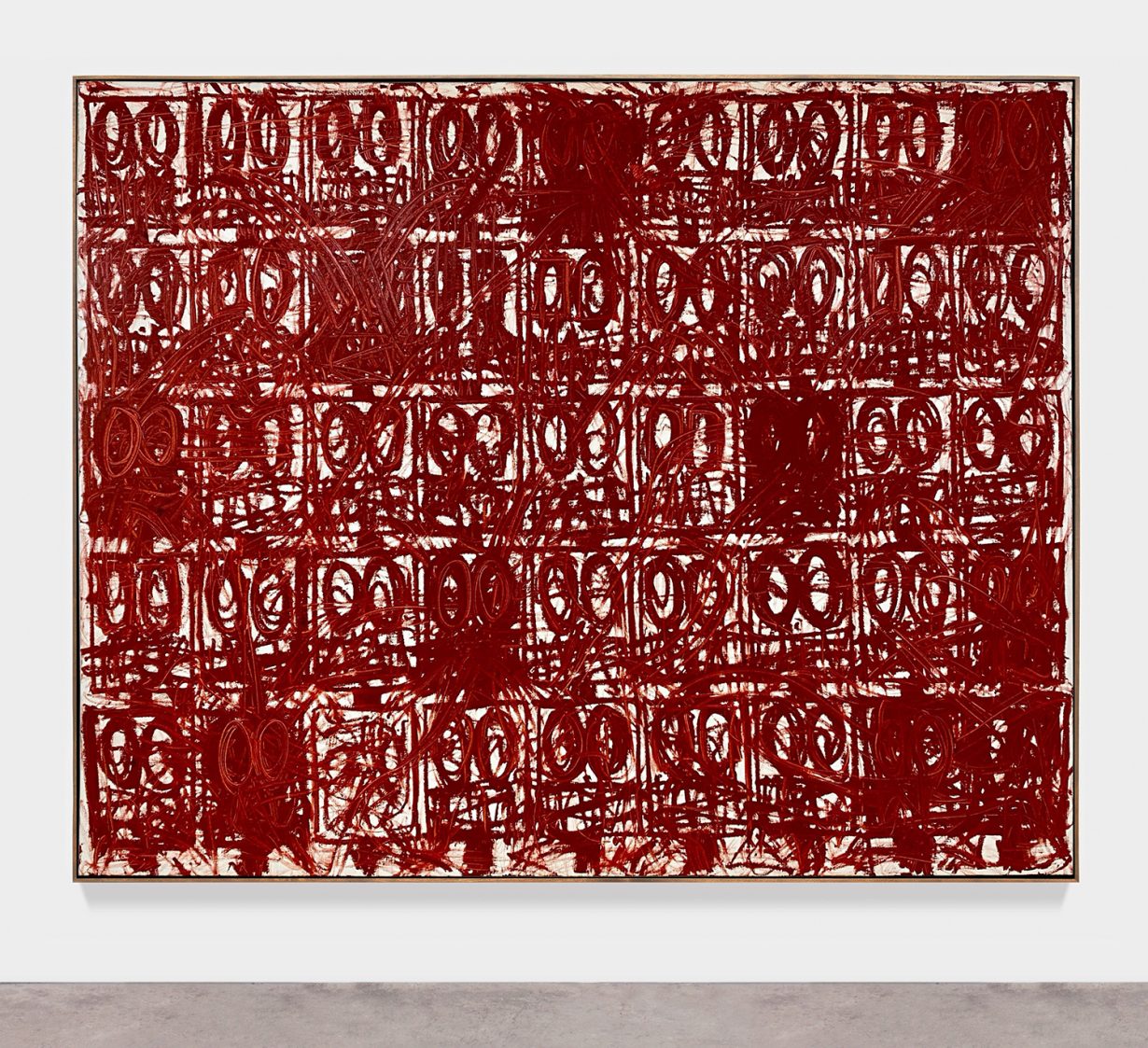

Following the end of the latest UK lockdown, New York-based Rashid Johnson’s solo exhibition, appropriately titled Waves (on show through 23 December) reopens across both spaces of Hauser & Wirth London. Featuring works created before and during the pandemic, the exhibition deals with themes of anxiety and breakdown, destruction and reconstruction and the relationship between individuals and collective societies. It draws on two bodies of work: the ongoing series of largescale tile mosaics, Broken Men, which the artist first presented in 2018; and a new series of paintings titled Anxious Red, created during the early stages of the pandemic and evolved from the artist’s Anxious Men series (2015–17). ArtReview caught up with him in late September before the exhibition’s (first) opening.

ArtReview How did you come to the Anxious Red drawings? Was it a sudden thing that happened during the early lockdowns?

Rashid Johnson It was an honest interpretation of where I felt like we were. I had come to Long Island from the New York City. We had left in a hurry. My son’s school had closed. We were looking and thinking about how to get away a little bit. There was a real urgency and it was a very specific moment.

Even looking back at it, even though it wasn’t particularly long ago, it was just the fear and the feelings that accompany that that were very fresh and very different. I had never felt that level of apocalyptic concern before.

I got to my house in Long Island and I said, “Well, I really want to make something.” I didn’t want to make something in response to what I was feeling, necessarily. It wasn’t intentional in that way. It just came about, quite honestly, I looked around, I said, “OK, I have some paper.” I hadn’t brought up materials. I hadn’t gone with the intention of working. I more or less escaped. I had some paper and I had some oil sticks and I happened to have this colour, Turkey Red. I’d never used it before, but I saw it and I thought, “This is the colour that I think I should be using right now.”

Then that led to me making my own red with R&F Paints in New York, and developing a colour that I call ‘Anxious Red’. Really, the Anxious Men were already a long-established body of work and they just needed to pivot. I felt like they didn’t speak to the urgency of the time, but when I made them red, it felt like they did. It was really quite simple, if I’m being honest. I wish that there was a more critically engaged story as to their birth, but it was just an honest response.

AR You call it a response, but do you think art can have an active agency beyond that? It seems as if there is a call for art to do more right now.

RJ I don’t know if I have an answer for that. The filmmaker Akira Kurosawa has a quote that I always thought was really appropriate: ‘To be an artist means never to avert one’s eyes.’ In a way, I really have taken that to heart, regardless of how I feel about a situation, I feel like I have to just keep looking, that I have to bear witness. That can be about the time you live in, that can be about any number of things, but I feel like as long as I keep my eyes focused, and I stay engaged and present, then I am effectively playing a role.

AR Has your reading of and thinking about the Broken Men works changed during lockdown and the pandemic and everything that’s come with it in terms of the visibility of issues concerning race, justice and colonialism for example?

RJ I think that they’ve always had so much opportunity to explore themes that were related to the times which they were made. I’ve always said that these things are collisions as much as they are collages or organisations of things. When people would ask me about the topics that these bodies of work address, I would really almost conjure whatever was happening on that day and say that the work was capable of consuming or considering those spaces, whatever was really present.

I think that, in a way, they’re doing what I intended them to do, which was to be nimble and to be present and flexible and organising themselves to address or to take into consideration whatever was in front of them. In that respect, I think that they’re really continuing to successfully arrange themselves around the current topics.

Something that I wanted for them was to have a sense of the absurd. That the characters have more or less graduated into really being deconstructed in a way where they’re just losing their minds, more or less. I think with what we’ve been facing around quarantine, in particular, the absurdity of being removed from our society and the complexity of that has definitely evolved how the characters are able to speak.

AR There’s this quite productive balance between order and disorder in the work.

RJ There always has been a kind of chaos in these works. I think that they’ve really vacillated within a conversation – that has been very present in my work, intentionally so, from the beginning – which is between abstraction and the conscious attempt to represent a concept or concern or an idea. I think in the work right now, there’s a sense that abstraction is beginning to win, in some respects.

AR Do you think that has something to do with the current times or is that just a direction they were leading you in anyway?

RJ In a way, it felt like they were going that way, but I think that what has been the result of their and my engagement with the current times is maybe pushing that narrative to abstraction more quickly than I imagined it would go.

AR Do you think the Anxious Red drawings have accelerated that further?

RJ I think the Anxious Red drawings have created a sense of urgency that has accelerated all of the themes and concerns that I’ve been negotiating over the last 10 years. It feels like everything is kind of amplified. There is a different sense of urgency and how we organise our expectations for what artists and what artworks are capable of.

AR Are you feeling that urgency in terms of the political and social situation in particular?

RJ I think art audiences and audiences of culture as a whole have turned to the artist in these moments and they say, “Well, how do we read this? How do we interpret this?”

I think it’s a challenge to art and to artists to say, “We don’t have those solutions.” To push back at the expectations, while at the same time, really figuring out how to tolerate and how to interpret and how to locate ourselves in this time. How to, in a sense, be both historians and illustrators. To say, “How do we conjure images at a time like this? How do we construct emotional narratives? How do we navigate the expectations that what we do will one day be interpreted for generations in the future to imagine what this time felt like?”

AR Do you feel a pressure of sorts?

RJ I think pressure is a privilege. It suggests that there’s enough reason for you to feel like either your themes or your ideas are going to be negotiated. I first am humbled by the privilege and then I address the opportunity. If I do feel pressure, I don’t find that to be pejorative or tragic. I find it to be a sense of how my agency and how my opportunity to amplify my voice becomes more significant in times like these.

AR A lot of the work that artists are making right now is necessarily ‘for the future’, because there are not so many ways to show it in real life. Has that changed the way you think about physical exhibitions?

RJ I’m of two ways of thinking on how we imagine the exhibition and its functionality and its agency in this time. I think that there is really an interesting opportunity to think about how exhibitions translate in digital space – a new architecture of exhibiting in space that traditionally we just use to disperse information rather than to emotionally engage with. This isn’t to say, in any way, that I prioritise or prefer online exhibitions because, from whence I came, I don’t. But you become accustomed to trafficking an exhibition or navigating an exhibition: walking into space, being confronted by walls and obstacles that then you navigate – you’re kind of led through a space. There are new walls in online exhibitions. Those walls can be didactics, they can be videos that inform how the work was informed. They can be antecedent concepts and concerns that the gallery or the artist can put as obstacles between works in order to help facilitate how you read or understand them.

This way of translating space and thinking about how exhibitions inform and what are the barriers and what are the things that facilitate your understanding, it’s kind of interesting, honestly. Now, having said that, I’m not sure exactly how to graduate my project to encompass all of these things yet.

AR Do you think that one obstacle, and not necessarily in a positive sense, can be the physical gallery itself? A lot of people can get put off by those kinds of spaces or feel they don’t belong in those kinds of spaces.

RJ I think that’s a real thing. I do see how there’s a barrier to entrance and how that can, for some people, maybe be frustrating. I’ve been exhibiting in and present around galleries for a long time. I am still sometimes a little flummoxed by the lack of engagement that people have with you when you enter. That’s not true of every gallery, but it can often be true. What other place do you come into and people don’t acknowledge that you’ve entered?

I think we have to do a better job in early education, whether that’s in middle or high schools, of telling people that galleries are free and you can go into them. You don’t have to be there to buy.

We use galleries as places to distribute some of our most impactful and our most engaged contemporary cultural concepts and if artists are going to continue to have their work presented in these spaces, we should do a better job of making them…

AR …more friendly?

RJ Yes, and more accessible, or making people feel like they should have access to them.

AR Going back to what you were saying earlier about maybe the ways you can use walls in a digital space for added context, do you think there can be too much of that? That the work becomes so heavily framed, in terms of how we are being told to understand and read it, that it shuts down? What’s interesting about the Broken Men series is that you can look at them 10 times and read them 10 different ways.

RJ Dealing with anything that was meant to be dealt with in person in a digital landscape is going to inherently have problems. It’s unlikely to be perfect. There probably will be people whose projects evolve to consume that, who begin to make work that is intended to be read in this context. I’m unlikely to be one of those people.

When my work does live in those spaces, I feel like I’m open to bringing in other tools that you often don’t have when you’re walking into just a clean white space, to help facilitate other ways of engaging. It’s like making lemonade. You figure out how to continue to amplify your voice in ways that you think are appropriate and thoughtful. I’m going to make art. I’m going to make art during a pandemic. I’m going to make art after a pandemic. I’m going to do whatever it takes to continue to push my ideas, my concerns, and the things that I’m looking at, thinking about. I just continue to be enthusiastic that people even want to participate in any way…

Rashid Johnson, Waves, is on view at Hauser & Wirth, London, until 23 December 2020