From Heavenly Creatures to Killing Eve, there’s a long cinematic history to the trope

When the perverse, erotic psychodrama Killing Eve first aired in 2018, I felt ambivalent. I have long been tired of the ubiquity of the psychotic, killer lesbian and/or violent, manipulative sociopathic bi woman in TV, film and literature. Four seasons later and the murderous, sociopathic assassin, Villanelle, is desperate to be good, saintly even. Having spent the first three seasons murdering people in some of the most heinous ways imaginable (death by poisonous perfume, cutting someone’s penis off, gutting a man while dressed in a Bavarian dirndl and a pig mask, trapping a man’s tie in the elevator door, and letting the elevator shaft do the rest), now she’s a changed woman – accommodating, deferential, sweet really.

In the first episode of the fourth (and final) season, Villanelle has found God and is living with a vicar and his daughter, May, who is clearly in love with the now temperate and sweet-natured murderer-for-hire. Trying to convince Villanelle of her goodness, the pair are about to kiss, and Villanelle, taken perhaps by the vulnerability of the moment and the pressure of so committedly trying to be ‘good’, dunks May’s head into a baptismal font, drowning her. In a moment of divine intervention, Villanelle stops herself, and celebrates that this has been a sign from God. The next episode is a different story however, and try as she might, Villanelle cannot help but kill, even when she really doesn’t mean to.

The trope of the mad, bad queer woman is hardly new. (Not to mention that the idea of criminality, psychosis and deviant sexuality as kindred spirits has a long history too). Think of queer-coded Mrs Danvers in Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938), Basic Instinct’s (1992) bisexual femme fatale Catherine Tramell, Daughters of Darkness (1971), Windows (1980), Heavenly Creatures (1994), Bound (1996), Monster (2003). So many of the lesbian or bi characters in these films experience excesses of rage and violence because of the homophobic society in which they live, pushed to murderous ends by shame and hostility (or, in the case of 2009’s Lesbian Vampire Killers, an ancient curse).

1994’s Heavenly Creatures and Sister My Sister were both based on true stories: the former dramatising the 1954 Parker-Hulme case in Christchurch, New Zealand, in which two teenage girls were convicted of murder – the victim being one of their mothers, and the latter concerning Christine and Léa Papin, two sisters who murdered their employer’s wife and daughter in 1933 in Le Mans, France. And in Michael Winterbottom’s 1995 film Butterfly Kiss, we meet Eunice, a bisexual serial killer, who takes the innocent Miriam under her wing, as both her lover and accomplice. Such films fall into scholar B. Ruby Rich’s landmark theorisation of the ‘lethal lesbian’ – a ‘new cinematic vogue for murderous women’ which emerged to prominence in ’90s filmmaking (in parallel, of sorts, to the era’s independent films of the New Queer Cinema movement).

In each these films, a pair of women must engage in a murderous plot, to fuel or maintain the intense bond between them. In Heavenly Creatures, for example, Pauline and Juliet, are threatened with separation because of their obsessive relationship, and are thus compelled by their sexual interests to kill in order to preserve their bond. As is so often the case in films of this period (and of the 20th century at large), (homo)sexuality is a repressed object, through which murder becomes a surrogate method to excoriate the excesses of desire.

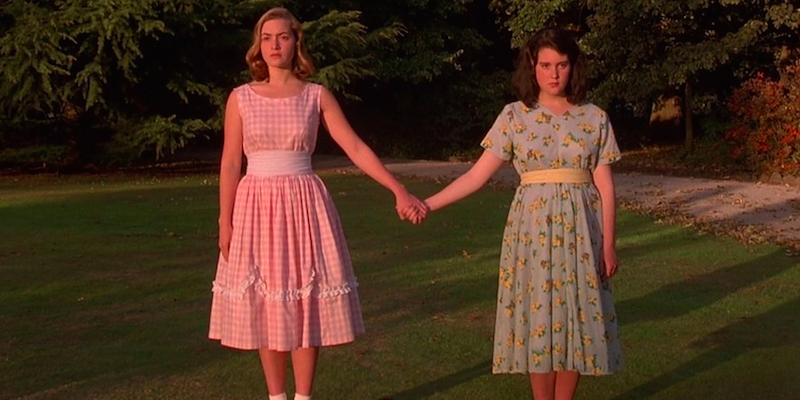

The aesthetics of this trope has generally vacillated between two extremes – either the women are infantilised, dowdy puritans (Juliet in a gingham tea dress, Pauline in a floral peplum outfit) or, as in the Wachowskis’ erotic crime thriller Bound, deeply glamorous, but vampish, often monstrous, red-lipstick-wearing femme fatales. Regarding the latter, Rich writes that the ‘newly stylish lesbian didn’t have to wear flannel shirts anymore or announce ideological positions; she could just buy clothes and go to dinner parties’.

Rich argues that this heady combination of sex and crime had its heyday in the 1990s for numerous reasons, including US militarism. Films such as Thelma & Louise (1991) and Basic Instinct, for example, signalled a shift in ‘women’s acceptable place in society just when US society was in the midst of being remasculinized and heterosexualized.’ Such films offered an alternative pop culture imaginary that appealed to women engaged ‘in vital political struggles’ as well as ‘glamorous cocktail parties’.

But what could this mean now? In Killing Eve, the combination of queer glamour and criminality lives on – violence is very much the new chic. The look is glossy, oozing with sex, style, and money. Indeed, if Villanelle is going to murder someone, then she may as well do it wearing Molly Goddard. Like the lethal lesbians of the 1990s, such representations transform the depressive, self-hating, villainous queer into empowered, self-assertive killers.

Take, for example Paul Feig’s A Simple Favor (2018). Emily (played by Blake Lively) is a thoroughly modern and murderous bisexual, liberated and loose in her sexuality. Tipsy, having spent the afternoon drinking martinis, she’s dressed in a low-femme, grey pinstripe suit, with a thick paisley tie, legs apart, exuding Big Top Energy. Emily then kisses her new ingénue friend Stephanie. Both spill secrets of middle-class ennui, and Emily’s growing resentment of her husband’s unprofitable and unsuccessful career. Like Villanelle, Emily is stylish, queer, confident and shame-free, entirely comfortable with who she is and who she has sex with. A Simple Favor proves that women can have it all – families, designer wardrobes, high-flying jobs, and murderous and same-sex desires to boot.

Similarly, Netflix’s recent comedy show Dead to Me (2019-2020) centres upon a murder plot and two middle-class women, one straight, one bisexual. In one moment, the two women are bonding in a bar doing shots and a man tries to approach them asking to dance. Jen (played by Christina Applegate) spits: ‘Do you see that we’re in the middle of something here? […] Read the room, fucko!’ Behold the rampage of the unhinged, violent but feminist (finally! So great to see women getting into a male-dominated industry!) woman – cynically deployed to cut through TV’s banal visions of domestic heteronormativity.

Murder, it seems, like queerness, has become a way to escape the tyranny of the liberal, bourgeois boredom of family life. For Killing Eve’s intelligence agent Eve, chasing Villanelle across the globe means leaving her well-meaning and domesticated husband, Niko. She is thrilled – turned on – by the chase. But are these new representations of the chic, self-possessed murderer – who may or may not fuck someone of the same sex, but it doesn’t really matter, because gender is a spectrum – the gains of sexual liberation given visual form?

There is something distinctively queer to me about that infamous image of Thelma and Louise diving off the edge of that cliff – annihilation, obliteration, freedom. But these more recent appearances of the murderous queer feel like lazy iterations of a potentially liberatory politics. Destruction and disorder might signal the abolition of heteronormativity in favour of alternative kinships and non-normative desires. (One of the most provocative scenes in Killing Eve is when, in the third season, Villanelle attempts to reconnect with her toxic family, only to set the house aflame, leaving them – we presume – to die). The temporary aberration to the moral status quo feels exciting, revelatory even. But what we’re left with when the dust settles are glossy, recuperative projections of flattened, liberal #girlboss feminism. Ditch the kids and nightly chores for the evening, the modern-day (empowered) ‘lesbian psycho’ tells us, as she adjusts her Loewe tuxedo.